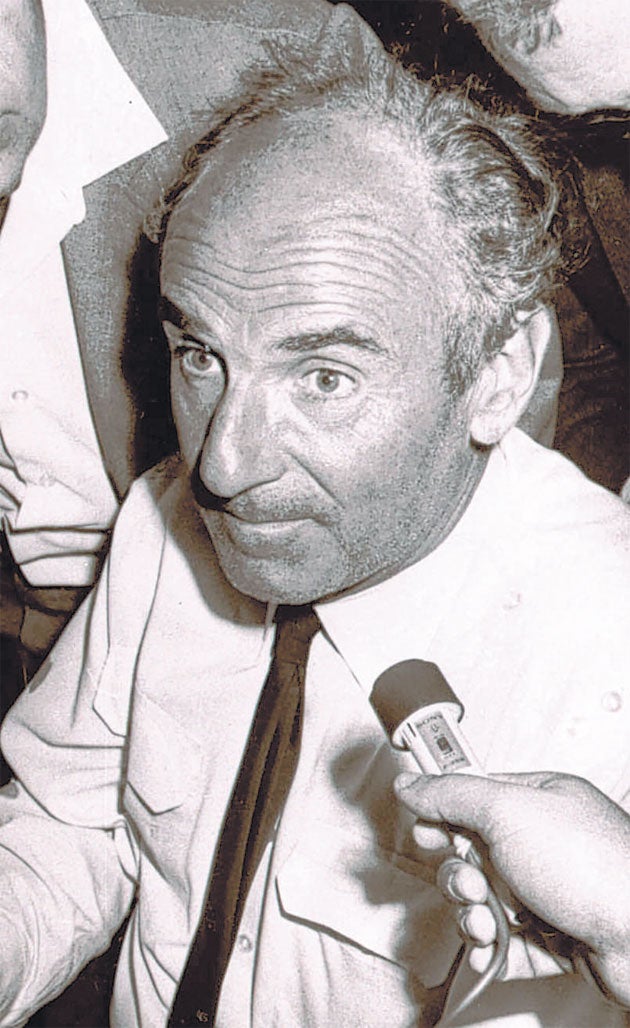

Reginald Levy: Pilot whose calmness under pressure helped end the 1972 Sabena hijacking

Reginald Levy was the English captain of a Belgian Sabena airliner hijacked by Palestinian Black September terrorists in 1972 after taking off from Vienna, and later stormed by Israeli commandos on the tarmac at Tel Aviv.

The commandos, who needed only 90 seconds to kill or disable the four hijackers and rescue the 100 passengers and crew, were led by Major Ehud Barak, now Israel's defence minister, and included Benjamin Netanyahu, now prime minister, who was wounded by a hijacker's bullet.

Drawing on his experience under German fire while bombing Hamburg and Berlin as part of RAF Bomber Command, Captain Levy remained coolness personified when two men wearing nylon-stocking masks burst into his cockpit on 8 May 1972, his 50th birthday. One put a gun to Levy's neck while the other held a grenade against the co-pilot's face. Only too aware that his wife was in the first row of First Class – Sabena had allowed her to join him for a birthday celebration in Tel Aviv – the captain famously told his passengers over the intercom: "As you can see, we have friends aboard."

The "friends" included two young women from Black September who were wielding Semtex-based bombs in the cabin, threatening to blow up the Boeing 707 unless 317 Palestinian prisoners were released from Israeli jails. Levy, surprised that he was being hijacked to his scheduled destination – Lod airport (now Ben Gurion) in Tel Aviv – transmitted a coded message to the control tower. He also got a message to his crew not to reveal that his wife was on board. After landing at night, the aircraft was guided to a remote tarmac, under the watchful eye of Israel's defence minister General Moshe Dayan, who sent out two saboteurs to deflate the tyres and disable the aircraft's hydraulics.

Told later that the aircraft couldn't take off, the hijackers started kissing each other in apparent farewell and spoke of blowing up themselves and the plane. Levy spent the night talking quietly to them, trying to calm them down. "I talked about everything under the sun, from navigation to sex," he said later.

The next morning, the hijackers sent Captain Levy to the terminal buildings with samples of their explosives to show they meant business. He took the opportunity to give Dayan details of where the hijackers were positioned and where the women had the black vanity bags carrying their bombs. He also provided the key fact that there was nothing blocking the emergency doors. Back on board, he said Dayan had agreed to their demands but the plane needed work before it could take off. Crucially, he also persuaded the hijackers to open the emergency doors slightly, due to the stifling heat in the cabin.

With the hijackers now elated, two lorries carrying 18 "mechanics" wearing white overalls drove up to the 707 and the men started tinkering beneath it. In fact, they were members of the élite Sayeret Matkal commandos, led by Major Barak. Climbing on to the wings and bursting through the doors, the commandos shot the two male terrorists dead, wounded one of the women and captured the other. The actual shooting lasted only 10 seconds. One woman passenger who stood up was fatally wounded. Six other passengers hit by bullets survived, as did the young commando Netanyahu.

It was four months later that Black September guerrillas launched their attack on the 1972 Munich Olympics, in which 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team died. After the Sabena hijacking, Black September threatened Captain Levy's family and he moved to South Africa. But he returned to Brussels after 18 months and would eventually retire in England.

Reginald Levy was born in Portsmouth in 1922 but the family moved to Lancashire when Reginald was a child, and he attended Blackpool grammar school and the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys – "The Inny" to its pupils – taking the ferry across the Mersey from Birkenhead, where his father, who was Jewish, owned the Scala cinema. From then on Levy considered himself a Liverpudlian, although he remained an unshakeable Blackpool football fan. (His uncle Alf owned another Scala cinema, on Liverpool's Lime Street, and his father's sister Muriel was "Auntie Muriel", the presenter of BBC radio's Children's Hour, a national institution at the time).

Aged 18, Levy volunteered for the RAF immediately after Dunkirk, as did his father, by then 44, who joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve as a signals officer. Reginald, widely known as Reg, was one of the first of 4,000 British trainee pilots to be sent to the US under the Arnold scheme to help turn the tide against the Luftwaffe. Back in the UK, based in Norfolk, he met his future wife Dora Shawcross, from St Helen's in Lancashire, who was then a flight sergeant responsible for discipline in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). They married in 1943 between his combat operations.

"During this time, I flew Bostons, Mitchells and even a captured German Junkers 88," Levy recently blogged on an ex-pilots' internet forum. But his serious combat operations began in Mosquito bombers in 1942 when he was part of 105 Squadron. In October that year, his Mosquito was hit by ground fire as he bombed Luftwaffe fighters parked at an airfield in Leeuwarden, the Netherlands. The entire nose of the "Mossie" was blown off, including his instrument panel, and the port engine was on fire, but Levy and his navigator managed to limp back to East Anglia where he crash-landed in a forest. "When the trees were coming through the windscreen, I remember thinking, 'I hope my watch doesn't break,'" he said. Both men survived and after two weeks in hospital and brief sick leave, Levy was back in the cockpit.

He moved from 105 to 51 Squadron and eventually to the 578 Squadron, where he flew Halifax aircraft from mid-1943 until early 1944, the period when Bomber Command took its heaviest losses, and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). He took part in the famous July 1943 Operation Gomorrah raids on Hamburg, at the time the heaviest assault in the history of aerial warfare. He finished his combat career with three raids on Berlin.

After the war, he served as an instructor for Air India, flew converted Lancaster bombers during the Berlin airlift and settled in Brussels in 1952 to fly for Sabena, where he would remain for 30 years. "I flew on practically all their aircraft," he said. "Over 50 types of aircraft and a total of 25,100 flying hours."

Reginald Levy, pilot: born Portsmouth 8 May 1922; married 1943 Dora Shawcross (died 2005; two sons, two daughters); died Dover 1 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments