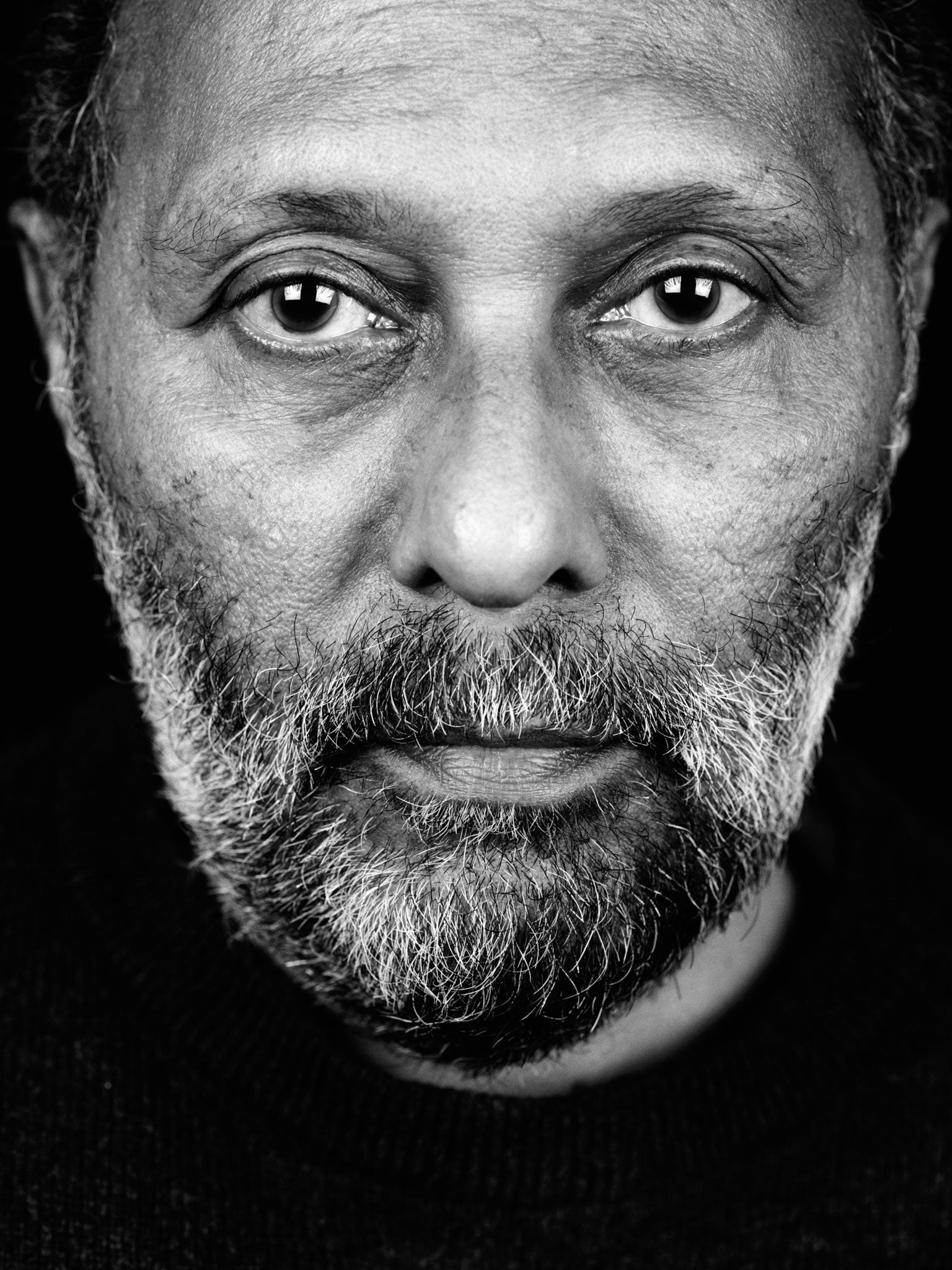

Professor Stuart Hall: Sociologist and pioneer in the field of cultural studies whose work explored the concept of Britishness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The sociologist and cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who has died aged 82, was an intellectual giant and an inspirational figure in the field of sociology. He was one of the founders of what is now known as "British Cultural Studies", which Hall and his colleagues pioneered in the mid-1960s. Professor Henry Louis Gates of Harvard University called him "Black Britain's leading theorist of black Britain."

Hall saw Britain as a country which is forever battling, within itself and with other nations. "Britain is not homogenous; it was never a society without conflict," he said. "The English fought tooth and nail over everything we know of as English political virtues – rule of law, free speech, the franchise." He noted sardonically that "the very notion of Great Britain's 'greatness' is bound up with empire. Euroscepticism and Little Englander nationalism could hardly survive if people understood whose sugar flowed through English blood and rotted English teeth." To sugar can also be added tobacco and cotton, as commodities which remain as a reminder of slave-trade Britain and its cultural legacy.

Hall was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1932, one of three children of Jesse and Herman Hall, an accountant. "We were part Scottish, part African, part Portuguese-Jew," he recalled of his family background, while also speaking of his "home of hybridity", which gave him diversity by nature and curiosity by nurture.

Following studies at Jamaica College he emigrated to Britain in 1951 on a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University, part of the Windrush generation of immigrants. The memory of sitting at Paddington Station after his arrival, watching the crowds, remained with him, accompanied by the eternal questions: "Where on earth are these people going to? And where do they think they are going to?". These questions and the quest for answers to them would characterise his life's work.

Hall commented on his time at Oxford that "in the 1950s universities were not, as they later became, centres of revolutionary activity. A minority of privileged left-wing students, debating consumer capitalism and the embourgeoisement of working-class culture amidst the 'dreaming spires', may seem, in retrospect, a pretty marginal political phenomenon." He also recalled that "I began not as somebody formed but as somebody troubled", suggesting that, "I thought I might find the real me in Oxford. Civil rights made me accept being a black intellectual. There was no such thing before, but then it was something, so I became one."

The Universities and Left Review (later the New Left Review) was founded in 1957, with Hall at the helm for the next four years. Professor Robin Blackburn, a former editor of NLR, told The Independent: "Stuart was the first editor of New Left Review. As a young student, I was deeply impressed by him but didn't know him that well at the time. He gave these marvellous talks in the basement of the Marquee Club, with other members of the New Left. I was influenced by his explanations of the origins of racism and its cultural roots. He later developed an analysis of neoliberalism [in the review Soundings], showing that free-market ideas do have an enormous attraction but also have relatively fatal consequences. He was a profound thinker, who got people considering the challenge of a multicultural society and saw that there were great problems with the concept of a 'British' nationality."

Blackburn noted that Hall did not produce one major, defining single work but that his legacy, and brightest thinking, comes through in the collections of essays which he edited, and to which he contributed, such as Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies (1996), which contains pieces by Hall and by those whom he had influenced.

Hall joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1957; in 1964 he married Catherine Barrett, who he had met on a CND march. The same year saw the first use of the term "Cultural Studies", by Richard Hoggart, and his establishment of the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS). Hoggart had read Hall's first book, The Popular Arts (1964), and invited him to become a director of the Centre. Hall later moved on to join the Open University as a professor of sociology in 1979, where he remained for the next 18 years. However, he retained connections with the CCCS until it closed in 2002, a victim of "restructuring" by the university's management.

Martin Bean, Vice-Chancellor of The Open University, said, "Stuart was one of the intellectual founders of cultural studies, publishing many influential books and shaping the conversations of the time. It was a privilege to have Stuart at the heart of The Open University – touching and influencing so many lives through his courses and tutoring. He was a committed and influential public intellectual of the new left, who embodied the spirit of what the OU has always stood for: openness, accessibility, a champion for social justice and of the power of education to bring positive change in peoples' lives."

In January 1979 Marxism Today published Hall's prescient, and now celebrated, essay, "The Great Moving Right Show", in which he discusses the early success of "Thatcherism", the term he coined for the then Leader of the Opposition's nascent policies. "The Heath position was destroyed in the confrontation with organised labour. But it was also undermined by its internal contradictions. It failed to win the showdown with labour," he argued. "It could not enlist popular support for this decisive encounter; in defeat, it returned to its 'natural position' in the political spectrum..."

Hall suggested that, by contrast, "'Thatcherism' succeeds in this space by directly engaging the 'creeping socialism' and apologetic 'state collectivism' of the Heath wing. It thus centres on the very nerve of consensus politics, which dominated and stabilised the political scene for over a decade." Hall later said of Thatcher's policies: "When I saw Thatcherism, I realised that it wasn't just an economic programme, but that it had profound cultural roots. Thatcher and [Enoch] Powell were both what Hegel called 'historical individuals'."

In 1994 Hall became Chair of the Institute of International Visual Art (Iniva), now based at Rivington Place in London, which hosts solo exhibitions of British and international artists, including Kimathi Donkor, Hew Locke and Aubrey Williams. The Institute's library was named in his honour. From 1995 to 1997 he was President of the British Sociological Association (BSA).

Last year Hall was the subject of The Stuart Hall Project (2013), a film by the artist John Akomfrah, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. The film had its genesis in a three-screen gallery piece, "Unfinished Conversation", currently showing at Tate Britain. Akomfrah told The Independent, "After working on 'Unfinished Conversation' it struck us that there was a lot more material that we had not used. The idea was to see whether a single figure could sum up the post-migrant experience. Hall was last of the great titans, who fundamentally altered how we look at ourselves and how we lived. He was unfailingly kind, courageous and absolutely principled."

More than 60 years after his arrival in Britain, Hall's quest for cultural identity was still in progress. As he said in the film, "We always supposed, really, something would give us a definition of who we really were, our class position or our national position, our geographic origins or where our grandparents came from. I don't think any one thing any longer will tell us who we are." He noted with pleasure that, in asking anyone in London today the question of where they are from, "I expect an extremely long story".

Stuart McPhail Hall, sociologist: born Kingston, Jamaica 3 February 1932; married 1964 Catherine Barrett (one son, one daughter); died London 10 February 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments