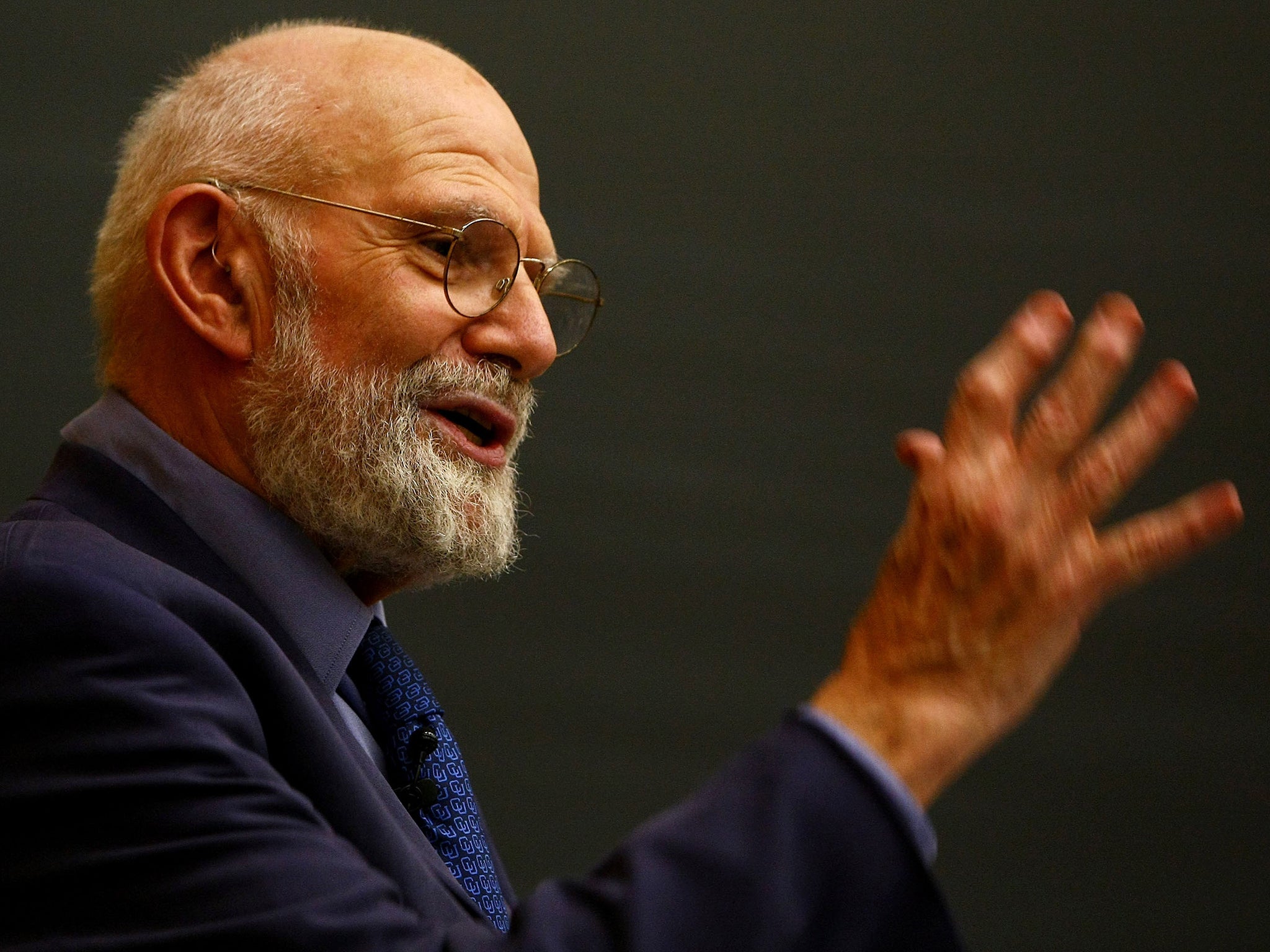

Professor Oliver Sacks: Neurologist whose writings illuminated the workings of the brain and explored what it feels like to be human

He wrote with compassion, casting his patients as the heroes of his stories

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Quite apart from the important therapeutic work he carried out, Oliver Sacks wrote a series of immensely readable books which shed light for the general reader on some of the mysterious workings of the brain. “It is the remarkable which captures my attention,” he once said. He wrote with clarity and compassion, casting his patients as the heroes of his stories, to bring a better understanding of the conditions he treated – and of the question of what it feels like to be human.

Baroness Susan Greenfield, Senior Research Fellow at Lincoln College, Oxford University, told The Independent, “He was a truly compassionate man with a fascination for the human condition in all its aspects, be it reflected in sickness or health, arts or science. His talents were all the more valuable because he could translate this fascination into a form that engaged with everyone.”

Sacks was born in London in 1933 to Muriel Landau, a surgeon, and Samuel Sacks, a physician. During the Blitz he and his brother were evacuated to Braefield School in the Midlands, where they experienced physical and psychological abuse. He later recalled, “When my brother Michael had his breakdown and became psychotic, one of the things he said was, ‘don’t call this a disease. It is my struggle, my world, my attempt to find meaning’.”

Returning to London when Braefield was closed down in 1943, he continued his education at St Paul’s School, Richmond. He created his own chemistry laboratory at home, guided and inspired by his Uncle Dave, or “Uncle Tungsten”, as the family called him, after his business of designing and manufacturing lightbulbs. Sacks graduated from The Queen’s College, Oxford in physiology and biology in 1954, following up with an MA and BM BCh.

During the 1950s and ’60s he experimented with hallucinogens, as he recounted told in a celebrated long essay, Altered States, published in The New Yorker in 2012. “I had done a great deal of reading, but had no experiences of my own with such drugs until 1953, when my childhood friend Eric Korn came up to Oxford,” he wrote. “We read excitedly about Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD, and we ordered 50 micrograms of it from the manufacturer in Switzerland (it was still legal in the mid-’50s).” The small quantity the pair had ordered had no effect.

He dabbled further with LSD, as well as cannabis and even morphine, for pleasure as much as from professional interest. But then, after taking amphetamines to excess on one too many occasions, he resolved to write a book. “The joy I got from doing this was real,” he recalled, “infinitely more substantial than the vapid mania of amphetamines – and I never took amphetamines again.”

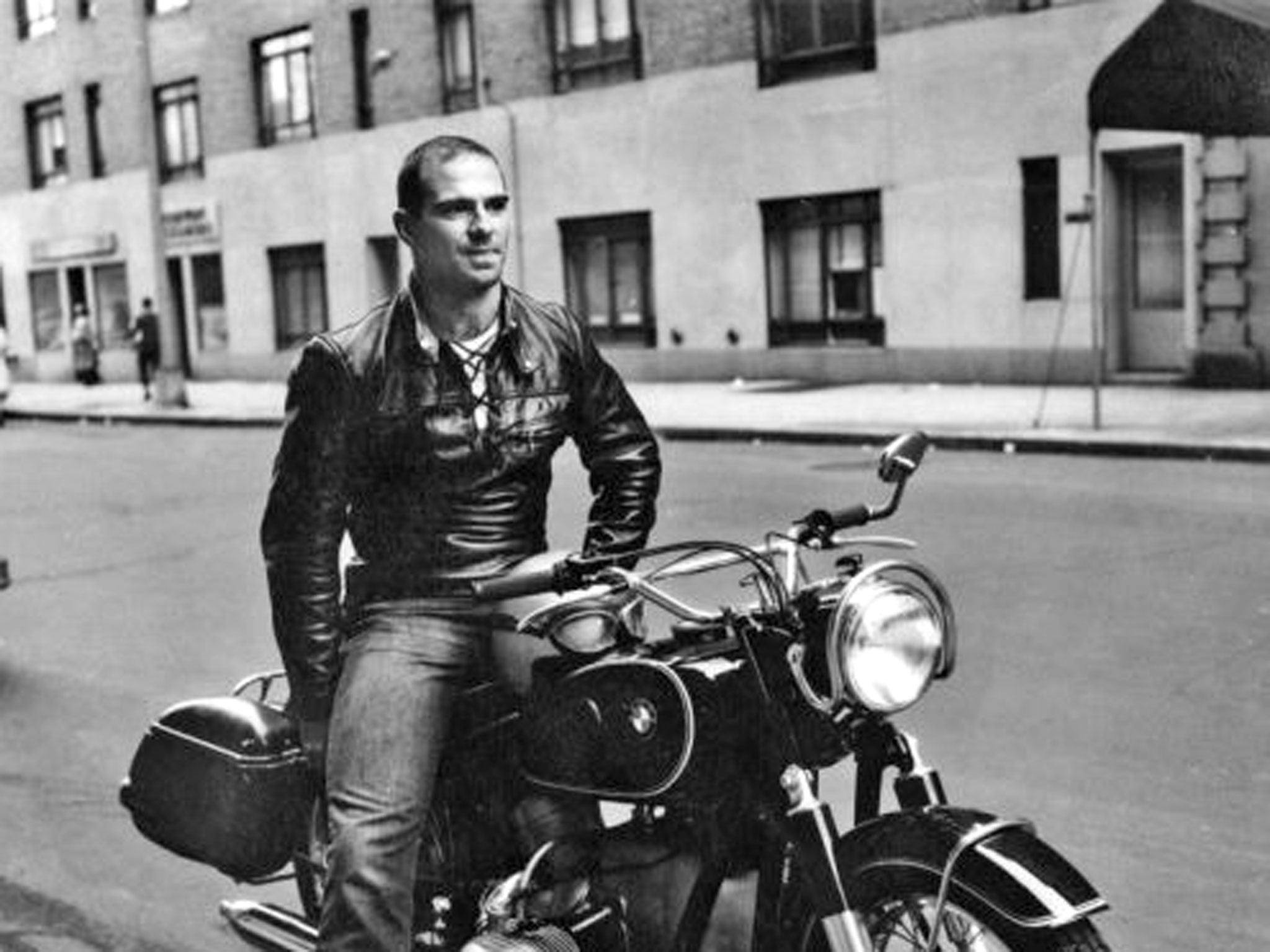

Sacks left England for Canada in 1965 and enjoyed the sense of freedom that the New World provided: “Somehow the physical spaciousness seemed to take on a moral and intellectual spaciousness as well.” A year later he moved to New York, where he practised at the city’s Beth Abraham Hospital.

His first book was Migraine (1970). “It was not until I arrived in New York and began seeing patients in a migraine clinic in the summer of 1966 that I began to feel a little stirring of the intellectual excitement and emotional engagement I had known in my earlier years,” he wrote. He was inspired, he said, by Edward Liveing, whose writings in the 19th century were an important contribution to the subject. “Who shall be the Edward Liveing of our time?” he wondered. And he answered himself: “You silly bugger! You’re the man!’”

In Awakenings (1973) he provided an account of the survivors of an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica, a sleeping sickness, which had struck in the 1920s and whose victims he treated in New York. As if to anticipate potential indifference for the topic, he noted, “Such a subject might seem to be of very special or limited interest, but this, I believe, is by no means the case...” He continued: “In the latter part of the book I have tried to indicate some of the far-reaching implications of the subject...” The reading public was certainly not indifferent to the book, which became a bestseller and established Sacks as a master of his genre.

This style of writing, with its alternation of narrative anecdotes and reflection, and what Sacks describes as a “proliferation of images and metaphors, its remarks, repetitions, asides and footnotes” became the model for all his subsequent works. Awakenings was later made into a film starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro and directed by Penny Marshall.

His best-known book was The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985), case histories taken from essays previously written for journals and periodicals. The “man” of the title is an opera singer, Dr P, whose disease makes him unable to recognise everyday objects. Sacks writes of their first meeting: “He also appeared to have decided that the examination was over, and started to look round for his hat. He reached out his hand, and took hold of his wife’s head, tried to lift it off and put it on. He has apparently mistaken his wife for a hat!”

The story was adapted as a chamber opera, with a libretto by Christopher Rawlence, and music by Michael Nyman, and was performed at the ICA in London in 1986 and shown on Channel 4 the following year.

Music, and especially the power of music on the workings of the brain, was a significant influence on Sacks. He explained in Musicophilia (2008) that for him “the first incitement to think and write about music came in 1966, when I saw the profound effects of music on the deeply Parkinsonian patients I later wrote about in Awakenings. And since then, in more ways than I could possibly imagine, I have found music continually forcing itself on my attention, showing me its effects on almost every aspect of brain function – and on life.”

Musicophilia tells the stories of a man struck by lightning who develops a passion for piano music, a deaf woman who experiences musical hallucinations, and provides fascinating examples of cases of synaesthesia, in which the different senses combine, overlap and interact. Each account, often detailing serious and incurable medical conditions, is rendered sympathetically, as if the author is sharing experiences with the patient as a friend rather than retelling a story from a distance.

Sacks founded the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function in 1995, in collaboration with the music therapist Dr Concetta Tomaino, whom he had first met 15 years earlier. The Institute develops and applies music therapies to help with cerebral disorders such as strokes, dementia and Parkinson’s.

From 2007 to 2012 Sacks was Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at Columbia University and was most recently Professor of Neurology at New York University School of Medicine. He published a volume of autobiography, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001), and his latest memoir, On the Move: A Life, was published in April this year.

It was in 2005 that Sacks first discovered the cancer that would eventually take his life. He wrote in a personal journal, reproduced in The Mind’s Eye (2010): “When the cinema screen went dark after the first preview, the spot that had been quivering to my left flared up like a white-hot coal, with spectral colours – turquoise, green, orange – at its edges. I was alarmed...” An ocular melanoma, a cancer of his right eye, was soon diagnosed.

Then, two years later, when his eye had to be lasered, causing him to lose part of his vision, he noted with characteristic fascination about his own situation: “The complete and sudden flattening of the visual world I had experimented with as a boy by closing one eye now became a permanent condition.” The effects of the loss of depth were dramatic and often surreal: “A woman’s strange green umbrella turns out to be a tree a hundred feet behind her,” he wrote.

In February in the New York Times he announced that the cancer had spread. “A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health,” he wrote. “At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out – a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver ... I feel a sudden clear focus and perspective. There is no time for anything inessential. I must focus on myself, my work and my friends.”

He ended by noting, “Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.”

Oliver Wolf Sacks, neurologist and author: born London 9 July 1933; CBE 2008; died New York 30 August 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments