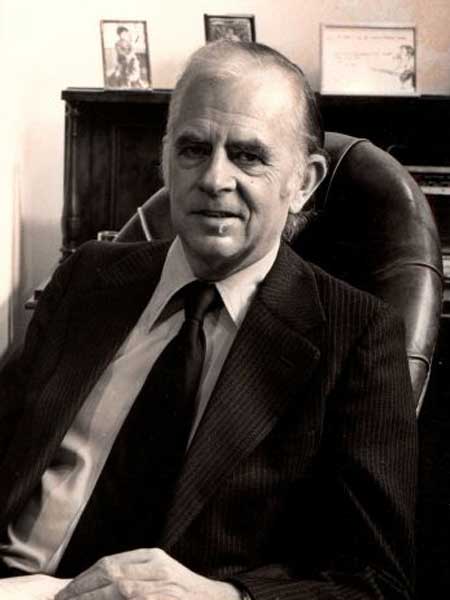

Professor Norman Morris: Humane obstetrician

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1960 the newly appointed Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School gave a lecture that greatly annoyed the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The professor was Norman Morris and in his lecture, "Human Relations in Obstetric Practice", he argued that medical advances over the past 25 years made childbirth less hazardous, but that many serious gaps remained in doctors' understanding of their patients' emotional condition during pregnancy and labour.

Morris described two- to three-hour waits on hard benches in rooms that looked like income-tax offices for a medical consultation that might last two minutes; women were given no opportunity to ask questions and were being left in ignorance about what was happening to them. He described women giving birth in delivery rooms where curtains prevented them from giving each other mutual support, but did not stop them from hearing and being frightened by other women's cries of pain. He said that obstetricians usually did little to support the physiotherapists and midwives who ran antenatal classes.

Why, he asked, are some women left alone during labour and shown scant kindness and sympathy? Why is there so little thought for the mother as an individual? Why do some hospital doctors seem cold and distant? Morris's lecture was published in The Lancet on 23 April 1960, and in 2005 it appeared in Vintage Papers from the Lancet, an anthology of the most important papers in the journal's 200-year history.

Norman Morris introduced many practices that are taken for granted now, but were revolutionary then. He invited fathers to attend the birth, and stopped the practice of shaving women's pubic areas and giving them enemas. When Sheila Kitzinger was writing The Good Birth Guide (1979) she asked Morris about the episiotomy rate at Charing Cross. He did not know: no one had kept records. She asked other obstetricians, and none of them knew. She said so in the book. Morris read it and was appalled. He started to keep records and then to question why this cutting was done. The episiotomy rate plummeted.

"Morris", Kitzinger said, "revered and respected women." Morris told his patients: "I cannot guarantee you the labour you want, but I'll do my best for you with the labour you have." While many senior doctors delegate out-of-hours work to their senior registrars, Morris did his share.

Norman Morris was born in 1920 in Luton; his father worked in local government and was a Nalgo shop steward, but his most powerful influence was his mother, a teacher, from whom Norman acquired his social conscience. He attended Dunstable School, where he was head boy and played in a hockey team that toured Germany in 1937. He trained as a doctor at St Mary's Hospital Medical School in London, qualifying in 1943.

He did his house physician and house surgeon jobs at St Mary's and in Amersham, followed by two years in the East End of London. There he met a local GP, Dr Benjamin Rivlin, a Russian Jewish immigrant, and married his daughter, Lucy. Their children were therefore Jewish, and they became a Jewish family, though Morris's origins were Christian. His wife and all his children are also doctors. The family had many intellectual, literary and musical friends, and R.D. Laing was once observed, balanced on his head, in their living room.

After National Service in the RAF, Morris returned to St Mary's and to the East End as obstetric registrar, working at Hammersmith, University College and Queen Charlotte's hospitals. Peter Nixon, a UCH obstetrician, was one of his role models, as were Alec Bourne and Grantly Dick-Read. In 1958 he was appointed professor at Charing Cross. It was an inspired choice: he had done relatively little research, but he was an able and humane clinician with a gift for people.

Such was his concern for his patients and colleagues that he arranged a weekly meeting of department staff with two psychiatrists present, where problems of patients' distress, or topics that upset the staff, such as dealing with stillbirth, could be discussed.

The inhumane approach to obstetrics was a British phenomenon, rarely encountered in Europe, and early in his career Morris made contact with the leading French obstetricians, especially Frédérick Leboyer and Michel Odent. He, in his turn, inspired young doctors and medical students to go into gynaecology. Sir Iain Chalmers, who was an obstetrician before becoming an epidemiologist, said: "In the 1970s, when the obstetric establishment was insisting on all sorts of rituals and routines in maternity units, Norman was a rare example of a senior obstetrician who challenged the establishment and encouraged others, including me, who were trying to do this. I was particularly inspired by reading his inaugural lecture."

Morris founded the Society for Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and also helped to found its international equivalent. He established a woman-run family-planning clinic at Charing Cross, and was a founder of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists' family-planning faculty. He also set up a postgraduate training programme in medicine surgery.

Morris took a strong pastoral interest in his trainees as well as his patients. During his time at Charing Cross he was Dean of Medicine at London University and Vice-Chancellor of the university. He retired as Emeritus Professor in 1985, but continued to work for the causes he believed in and eschewed private practice. He fought, unsuccessfully, to save his maternity unit when it was at the West London Hospital in Hammersmith, but ensured that its fine Doulton murals were transferred to the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital.

Morris was a trustee and former chairman of the Little Foundation, a charity that worked towards giving babies the best start in life. When the Catholic-owned Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth recently decided to force a religious-based ethical code on its gynaecologists, he set up a committee to fight it. It was after a committee meeting that he collapsed on the steps of the Athenaeum with a thoracic aneurysm, dying in hospital shortly afterwards.

Caroline Richmond

Norman Frederick Morris, gynaecologist and obstetrician: born Luton, Bedfordshire 26 February 1920; Registrar, St Mary's Hospital, Paddington 1948-50, Senior Registrar 1950-52; First Assistant, Obstetric Unit, University College Hospital 1953-56; Reader in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, London University (at the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology) 1956-58, Professor (at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School, later Charing Cross and Westminster Medical School) 1958-85 (Emeritus), Dean, Faculty of Medicine, 1971-76, Deputy Vice-Chancellor 1976-80; Medical Director, IVF Unit, Cromwell Hospital 1986-97, Director, Department of Postgraduate Medicine 1997-2005; President, International Society of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 1972-80; Chairman, Association of Professors of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the UK, 1981-86; Chairman, British Society of Psychosomatic Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Andrology 1988-96, President 1996-2008; married 1944 Lucy Rivlin (two sons, two daughters); died London 29 February 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments