Professor Malcolm Clarke: Acclaimed authority on the sperm whale and giant squid

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Malcolm Clarke was an international expert on two animals which remain among the most mysterious on the planet: the sperm whale and the giant squid. He spent most of his adult life pursuing these creatures, from the whaling grounds of the Antarctic,to the deep waters off the Azores – the remote archipelago where he lived latterly, within daily sight of his subjects.

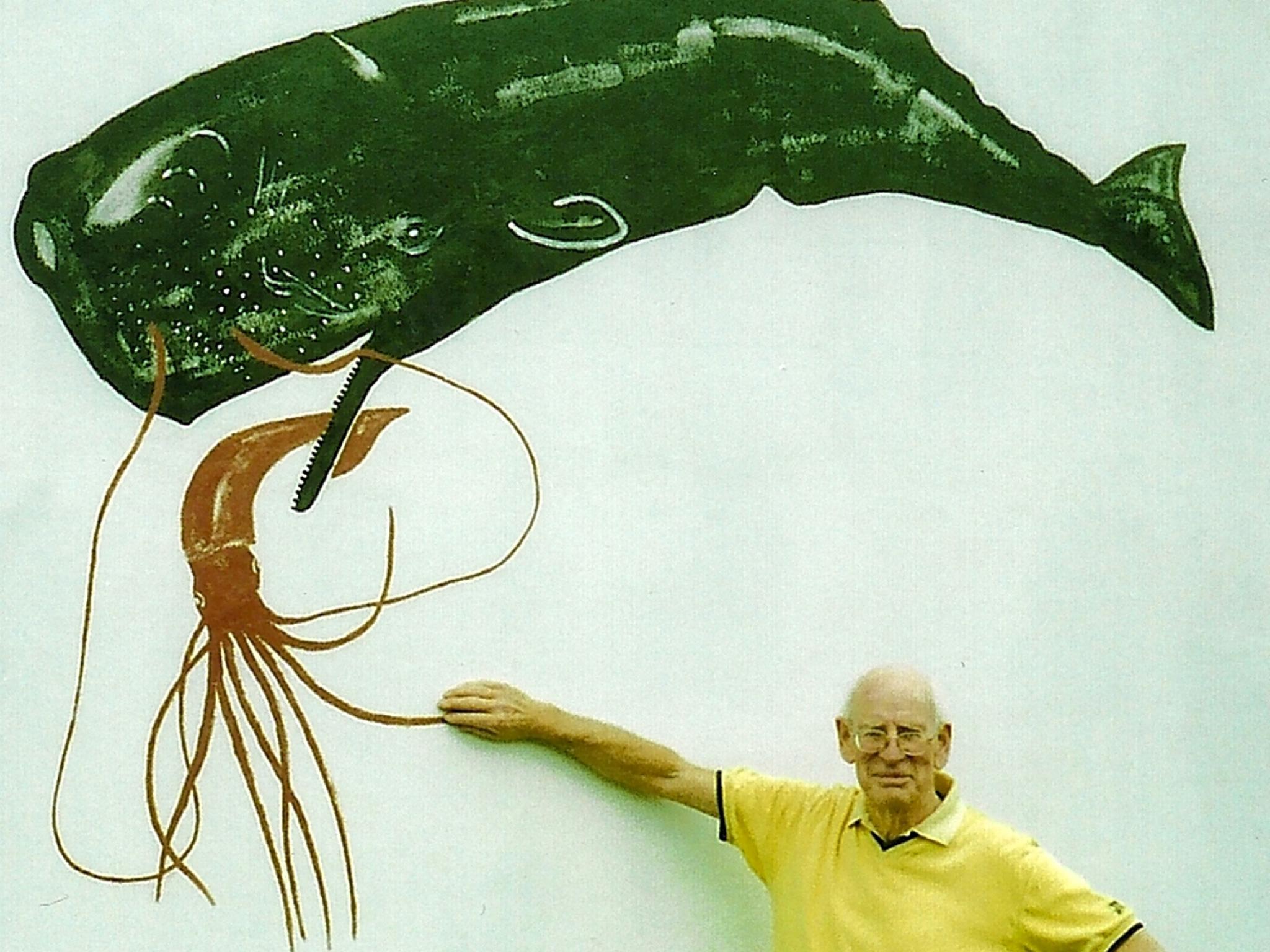

There, on cliffs of the island of Pico – a black lump of volcanic rock in the mid-Atlantic – Clarke built a remarkable museum (in his garage) dedicated to sperm whales and squid. Inside was a lifesize mural of the largest female sperm whale found off the Azores. Outside stood a skeletal whale, similiarly full-sized, modelled in metal tubing. The effect was akin to a creation by Salvador Dali, a surreal impression only strengthened by the giant fabric squid hanging from the ceiling and sewn, to exacting dimensions, by Malcolm’s wife Dot. On my first visit there, with the BBC director Adam Low, Clarke took us into the grounds of his museum and from a giant tub filled with sea water fished out a large squid beak and handed it to me as a keepsake.

This tall, softly spoken man had spent his life with the monsters of the deep, and knew their secrets. From his shelves he produced a coffee jar filled with an odiferous lump of dung – ambergris, the almost mythic product of a whale’s lower intestines, still prized today as perfume fixative by the likes of Dior, Givenchy and Chanel. The smell stayed on my fingers for days.

Malcolm Clarke was born in Birmingham in 1930. As a young man he did his National Service in the Royal Army Medical Corps from 1948 to 1950; he recalled driving patients from Aldershot to the monumental military hospital at Netley, on Southampton Water. After an early stint as a teacher in a Scunthorpe secondary modern he studied zoology at the University of Hull, and from 1954 to 1955 served as a government inspector on whaling ships in the Antarctic at a time when Britain was still a whaling nation.

He told me how the ship on which he was sailing caught 3,500 whales that season, and the fleet as a whole took 30,000 whales. The onboard butchery stayed with him: “We were at full cook the whole time,” sometimes taking 24 whales a day. Yet the young scientist saw the opportunities this terrible cull presented, via the vis-ceral availability of these still largely unknown creatures which spend 90 per cent of their lives in the depths.

Sperm whales can dive for up to a mile, and spend two hours down below feeding on squid. Clarke recalled one whale caught off Madeira whose stomach was found to contain 18,000 squid beaks. As a result, he became as interested in the enigmatic lives of the cephalopods as in the cetaceans.

Indeed, he told me in 2006 that whales had begun to annoy him, because they so voraciously ate the rival subjects of his studies.

Dr Rui Prieto of the University of the Azores recalls that Clarke worked in every ocean during his career, from South Africa, Australia, Hawaii, and the Faroe Islands. “He was happy as a child when handling a gooey Haliphron atlanticus [a seven-arm octopus], as I’ve seen him doing at sea because he was unable to wait until we were back on land.”

As he guided visitors around his eclectic museum, Clarke was full of arcane details: the fact that whales see only a blue-green spectrum, these colours being most useful in deep waters; that the bones of a whale are filled with oil – if they were filled with air they would explode as the whale dove into the pressurised water; and how the sperm whale has four stomachs, their intestines filled with thousands of parasitic nematode worms. It was “a disgusting sight”, he recalled, when the whales were cut open on the deck of a whaling ship.

His career spanned the eras of whaling and modern whale science. Few scientists could boast that lifelong, physical contact with their subjects. “When I went whaling nobody cared a toss about the whales, really,” he said, in his bluff, still faintly Birmingham accent.

It was at least partly due to his efforts that that changed. He contributed to 150 scientific papers and edited six books. Richard Sabin, Curator of Vertebrates at the Natural History Museum, said, “Malcolm was a very generous man; he was always giving of his time and willing to share his knowledge and experience… His research on giant squid and sperm whales generated new knowledge and led to a deeper understanding of the biology of these organisms.”

Clarke’s expertise gave him a global voice. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1981 for his work on the squid, and was visiting fellow at the National Oceanographic and the University of the Azores, where he was the first port of call for the BBC, Channel 4, National Geographic, the Discovery Channel and the Open University.

Hal Whitehead of Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia, the pre-eminent contemporary expert on sperm whales, recalled that Clarke was “for many years our main route into the strange world of the big animals in the deep oceans… He was very much the hands-on scientist, and retained immense enthusiasm for the animals he studied until his death.” Unfailingly interested and interesting, he was still working the day he died, from a heart attack.

Malcolm Roy Clarke, marine biologist: born Birmingham 24 October 1930; Senior Principal Scientific Officer, Marine Biological Association 1978–87; married 1958 Dorothy Clara Knight (three sons, one daughter); died Pico, the Azores 10 May 2013

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments