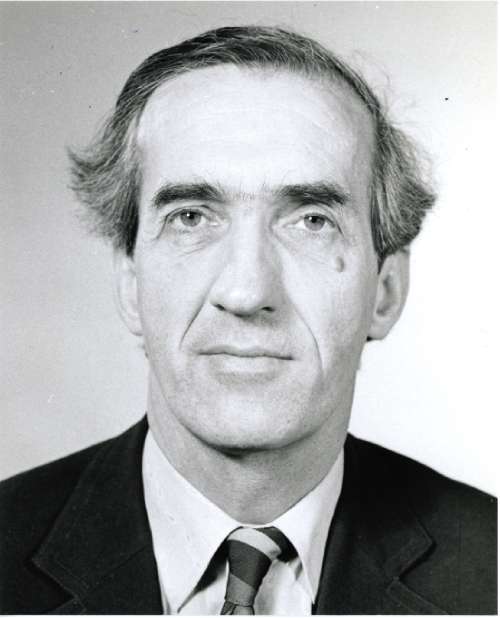

Professor Brian Cox: English scholar, poet and editor of 'Critical Quarterly' whose Black Papers sparked debate on education

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Brian Cox was a gifted teacher, a superb editor, a skilled administrator and a considerable poet. In another life he might have been a vice-chancellor or perhaps a junior minister for education. However his commitment to the teaching of English, both reading and writing, meant that much of his working life was devoted to raising the standard of debate about education in general and the teaching of English in particular.

Cox was born in 1928 in the town of Grimsby in Lincolnshire, then a huge fishing port, to a poor family hovering on the borders between the working and the lower middle class. From the first, education was an absolute value and Cox's autobiography (The Great Betrayal, 1992) provides a vivid account of his schooling at Nunsthorpe elementary and Wintringham Secondary schools. Cox was ambitious and self-possessed enough to put himself in for the scholarship exams to Cambridge and to win an exhibition to read English at Pembroke College in December 1946.

Before going up to university, spells of teaching in the Army during national service and as a supply teacher meant that Cox had a surprisingly wide knowledge of teaching and teaching methods. Cambridge provided two further experiences: the inspiration of his undergraduate course in English, which provided both close supervision and great freedom, and the sterile years of graduate study on Henry James for which he was inadequately prepared and inadequately taught.

In 1954 as Cox was preparing to marry, he and his future wife Jean decided that he would apply for a job at any university in Britain except Aberdeen (too far north) and Hull which, as they were both from the neighbouring town of Grimsby, they knew well. Thirteen unsuccessful job applications later, Cox applied for and obtained an Assistant Lectureship at Hull. Hull provided Cox with a stimulating set of colleagues: Richard Hoggart, Malcolm Bradbury and Barbara Everett all taught there in the Fifties, and, above all, from 1955 there was the presence of Philip Larkin as librarian.

At Pembroke Brian Cox had formed an extremely close friendship with A.E. Dyson and together they elaborated a shared position that accepted the Leavisite claim that literature demanded the most serious moral attention, but rejected the sectarian dismissal of contemporary writing. At the end of the Fifties they felt sure enough of their own tastes to start a small magazine, Critical Quarterly, as a focus both for critical writing that shared their estimation of the Leavisite legacy and for contemporary poetry.

The magazine was wildly successful, publishing a whole new generation of critics such as Raymond Williams, Frank Kermode, David Lodge and Tony Tanner. Even more successful was the poetry, which included Ted Hughes, Thom Gunn, Philip Larkin, and the winner of one of their first poetry competitions, Sylvia Plath. This success spawned a small business as circulation climbed to 5,000 and the magazine sponsored successful weekend schools aimed at sixth-formers. This development led in turn to the setting up of a second magazine, Critical Survey, aimed more directly and practically at sixth-form teachers.

It was while discussing a special issue of this magazine looking at contemporary development in education that the idea of a "Black Paper" (in contrast to government White Papers) was born. In its initial conception the Black Paper was mainly concerned with the student sit-ins then common in British universities. Cox had spent a year at Berkeley in l964-5 and had moved from supporting the Free Speech movement to condemning its tactics of disruption. As the issue took shape, however, a second focus was added: the failures of comprehensivisation and theories of progressive education.

The combination was explosive and for the next six years, and further Black Papers, Cox was often in the news as he defended his positions, now backed by a formidable array of evidence that comprehensive education was leading to a more unjust and unequal society.

The slightly hysterical focus on student occupations soon disappeared and subsequent Black Papers marshalled arguments and facts to illuminate a very confused national debate. By 1975 it might have been possible to see Cox heading for a junior role in Thatcher's first government but that year his elder brother, suffering from incurable cancer, committed suicide and, in the subsequent emotional turmoil, Cox decided both to intensify his commitment to writing poetry and to focus his political efforts on the teaching of English.

Those efforts culminated in his membership of the Kingman committee in l987-8 and then chairing his own committee on the teaching of English in 1989. The Cox Report marks a real achievement in bringing genuine intelligence to bear on the questions of how a standard language should be taught. While stressing the importance of the teaching of the standard, the Cox Report also emphasised the importance of valuing non-standard forms of the language and allowing pupils to explore their own linguistic resources.

These sophisticated and humane recommendations, which also included Cox's long-time commitment to the teaching of creative writing, did not suit a Conservative government that had a fixation on teaching traditional grammar. In an extraordinary move, Kenneth Baker, Secretary of State for Education, who had commissioned the report, decided that the three final chapters of recommendations would be published ahead of the 14 chapters that elaborated the complex arguments the committee had considered.

The Cox Report is a high-water mark in the attempt to reform the traditional teaching of English in the light of current linguistic knowledge. The Government, however, had no interest in its recommendations and refused to provide the money for the provision of necessary teaching materials. Cox was most disappointed that the recommendations he had fought so hard for were not implemented. He did, however, take some solace from the fact that the epithet of "reactionary", awarded to him by the tabloids after the publication of the Black Papers was, in the aftermath of the Cox Report, replaced by "woolly liberal".

Cox had moved to a chair at Manchester University in 1966 and he was active as a university administrator both as Dean of Arts (1984-86) and Pro Vice-Chancellor (l987-91). These administrative skills were put to good use in retirement when he served both as chair of North West Arts (1994-2000) and as chair of the Arvon Foundation (1994-97). In all these roles and in handing on Critical Quarterly to a younger generation of editors, Cox saw himself as someone whose purpose was to develop the possibility of aesthetic experiences for others.

Few men can have enjoyed their retirement more, and his pleasure in it and in his family is recorded in the poetry, which had become more and more important to him. The first two volumes, Every Common Sight (1981) and Two-Headed Monster (1985), were followed by Emeritus (2001) and My Eightieth Year to Heaven (2007). The poetry records simple events and emotions: love of landscape and family, the shock of the onset of death. Cox's use of language and form is deceptive and at first reading the poems often seem slight, but read together and read again the poems declare real ambition. The writing urges a constant pleasure in the simple continuities of life and art, pleasures only sharpened by the awareness of mortality.

Colin MacCabe

Charles Brian Cox, English scholar, poet, editor and educationist: born Grimsby, Lincolnshire 5 September 1928; Assistant Lecturer, then Lecturer, in English, Hull University 1954-66; Co-editor, Critical Quarterly 1959-2008; Professor of English Literature, Manchester University 1966-76, John Edward Taylor Professor of English Literature 1976-93 (Emeritus), Dean, Faculty of Arts 1984-86, pro vice-chancellor 1987-91; Co-Editor, Black Papers on Education 1969-77; Chairman, National Council for Educational Standards 1979-84, Presiden t 1984-89; Chairman, National Curriculum English Working Group 1988-89; CBE 1990; FRSL 1993; Chairman, North West Arts Board 1994-2000; Chairman, Arvon Foundation 1994-97; married 1954 Jean Willmer (one son, two daughters); died Cheadle Hulme, Cheshire 24 April 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments