Oscar Niemeyer: The last of the 20th century’s great heroes of architecture, who remained an obdurate outsider

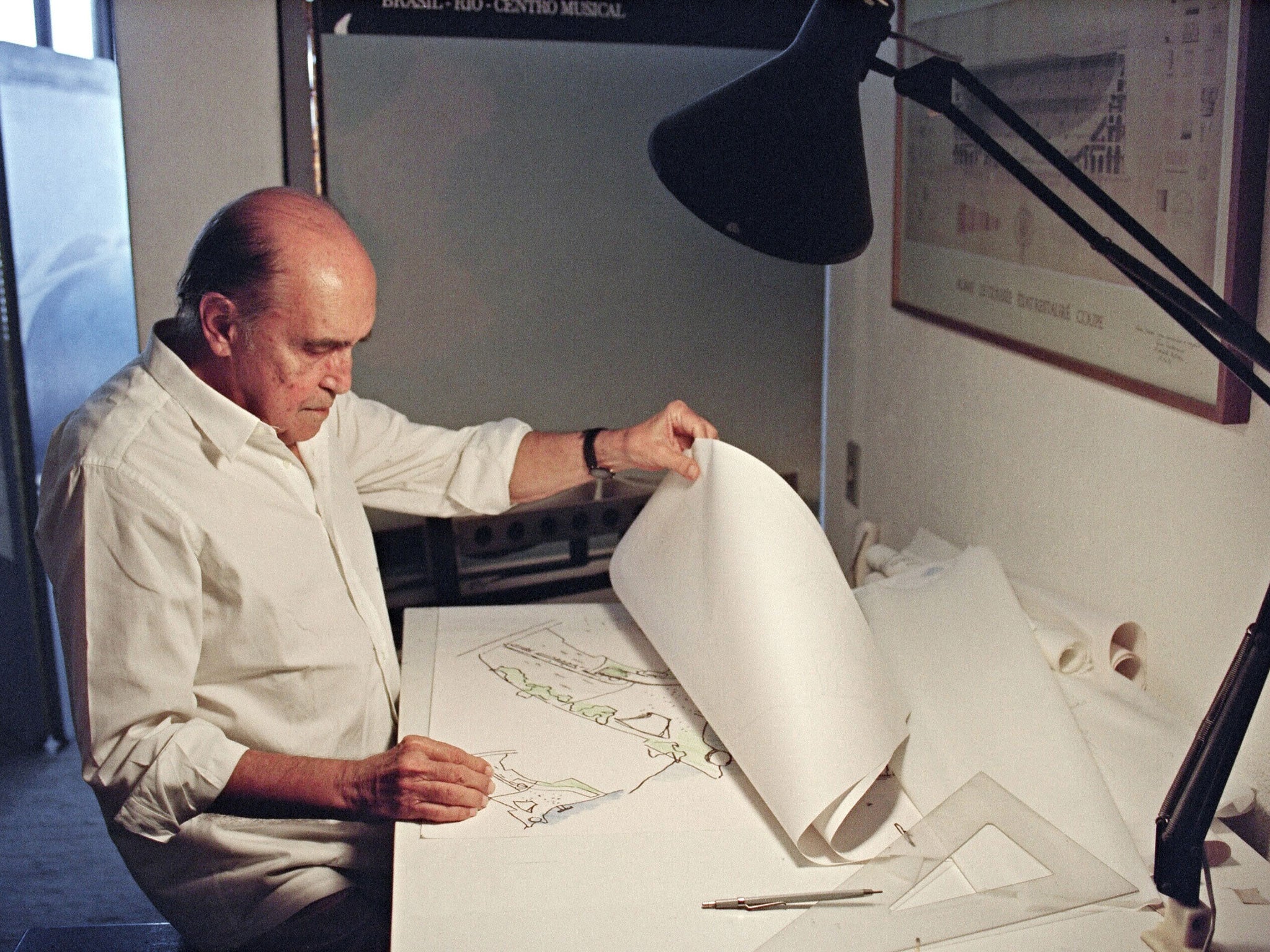

He possessed a Matisse-like ability to convey potent shape and movement with few marks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The passing of the last of modern architecture’s great mid-20th century heroes closes the book on an extraordinary architectural period whose various radical social and political intents have evaporated from the mindsets of the 21st century’s architectural giants. Nevertheless, Oscar Niemeyer’s presence can be linked to the creative processes of architects as sharply diverse in ethos and aesthetics as Lord Foster, Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid.

Only once did Britain experience the Brazilian’s dazzling skill, when Julia Peyton-Jones, Director of the Serpentine Gallery, commissioned him to design the gallery’s temporary pavilion for the summer of 2003. Niemeyer’s offering followed highly unusual structures on the site by Daniel Libeskind and Toyo Ito, both working closely with Cecil Balmond. But Niemeyer’s pavilion took the breath away: here was an act of the purest architectural grace whose rhythms and proportions recalled the idea of architecture as something pure and permanent.

The pavilion’s grace was created, like most of Niemeyer’s architecture, in a tiny anteroom outside his formal office, where the architect – distinctly short in stature – stood at a chest-high, not quite horizontal drawing board. The pavilion’s form arrived in a brilliantly cursory manner, the latest in a long line of architectural glissandi that flowed from Niemeyer’s preferred thick black felt-tip pens; as usual, the outline and perspectives were sketched out rapidly. He possessed a Matisse-like ability to convey potent shape and movement – characteristically, in nude figures as well as buildings – with very few marks.

Niemeyer’s uniquely sensual architecture has only been surpassed in terms of long-term canonic individuality by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Alvar Aalto and Louis Kahn. That deified quintet of visionaries shared a common popular advantage over Niemeyer. They were outgoing and they polemicised more powerfully; they travelled and taught at the universities that mattered; they were either sartorially notable or photogenic, or both. And, thus, their brilliant pronouncements spread outward in deltas of irresistibly stated metaphysics, aphorisms and monographs: less is more, form equals function, machines for living in.

Their buildings represented startling new ideas in solid form, opening the doors to a laboratory of architectural experiment which demanded vastly more than new modes of decoration, style or physical articulation. The search for apparently perfectable structures and spaces in an era cross-currented with fulminating consumerism and westernised socialist ideals produced architecture that redefined, in those countries that could afford it, the relationship between people and buildings, and between buildings and places.

Niemeyer was a crucial, yet ambiguous, figure in this revolution, the insider with more than a little of Camus’ L’Etranger about him, who said of his design of Brasilia’s cathedral: “I was not concerned with how cathedrals had been made before. And I don’t believe in anything, but I tried to feel like a Catholic when I was designing it.” He possessed a radical originality that he always felt had been partially obscured by the fierce, penumbral glow of Le Corbusier’s reputation.

In April 2003, in his 10th floor penthouse studio overlooking the Avenida Atlantica and Copacabana beach, Niemeyer recalled Corb’s visit to Brasilia, the new capital city in the bush that he, Lucio Costa and the engineer Joaquim Cardoso, completed in the 1960s. Here was Big Bang modern architecture on a massive scale – bigger even than Chandigarh, the Indian political capital that Corb had designed for Nehru a decade earlier.

“When he saw the presidential palace at Brasilia, he said it was beautiful,” murmured the dapper nonagenarian in his razor-creased slacks, crisp white shirt and scrupulously pulled-up socks rising from beautifully made cuban-heeled loafers. “He said it was highly intelligent.” Niemeyer raised his cheroot for effect and examined, with those unnervingly still eyes, his audience of three British journalists. “But I was not fooled by this comment. It was just the politics of being neighbourly. Le Corbusier is a major figure, but a small architect.”

Niemeyer had two key professional encounters with Corb, the first auspicious and encouraging, the second rather salutory. In the late 1930s, and newly graduated from the Escola Nacional de Belas Artas in Rio de Janeiro, he assisted the Swiss architect on the design of the Brazilian Ministry of Education and Health in Rio. Almost two decades later, an eminent jury picked Niemeyer’s scheme in the design competition for the United Nations Secretariat complex in New York ahead of Corb’s. But it was the latter’s revised site masterplan, influenced by Niemeyer’s version, that was finally selected after behind-the-scenes discussions.

Niemeyer also described, with subtle disdain, the visit of Walter Gropius, arguably modernist architecture’s primal figure, to his villa in the hills beyond Ipanema. Gropius complained that the irregular, amoeba-like plan of the Casa dos Canoas, one of modern domestic architecture’s absolute icons, could not be mass-produced. Niemeyer thought the judgement petty. Straight edges and rigidly rectilinear forms – “the chill and elemental structures of Mies van der Rohe” – were anathema to a man who owed more to the imagination and delirium of Gaudi. Receiving architecture’s Oscar, the Pritzker Prize, in 1988, he quoted Baudelaire’s dictum that “the unexpected, the irregular, the surprise, the amazing, are an essential part and characteristic of beauty.”

He felt less confrontational towards Wright. “I did not meet him,” he said wryly in 2003. “I’m not that old.” The remark, plainly inaccurate in terms of the possibility of their meeting, implied that, architecturally, the Brazilian felt relatively detached from the great Chicagoan’s influence.

Niemeyer’s position on the very cornice of architecture’s 20th-century pantheon depended, in great part, on a nexus of influences that set him apart from the other great purveyors of what came to be known as the International Style. Niemeyer’s modernism may have been informed by the techno-socialist tenets of Gropius’s Bauhaus movement, but one other factor, coupled with a Damascene moment in Venice, set him apart from the equivocal socialism of the Bauhaus and, later, from the trend in the 1950s towards increasingly refined rectilinear expressions of structure, which reached pluperfection in van der Rohe’s 1958 Seagram Building in New York.

Niemeyer was profoundly sensual, as dye-stamped with the characteristic as any other carioca, despite his upper-middle class origins. And the sensualism was alloyed with a mordantly Quixotic sense of quest, set against implacably desolated fate. The creation of Brasilia required dozens of arduous road trips to “that large and dismal patch” of Minas Gerais. Niemeyer feared aircraft, and usually took the same four friends with him, because they needed the money, were good company and, quite specifically, because they knew nothing about architecture.

It was the kind of company he often kept in Rio in his self-confessedly orgiastic (his word) youth. He once recalled, with casual brio, urinating the methyl blue solution given him for gonorrhoea, and spoke with affection of Eloa’s bar at Porto Alegre in 1944, where the girls “had the baroque buttocks we favoured.”

The baroque was, indeed, the key to Niemeyer’s mature architectural vision. And it was in Venice that his search for a more plastic form of modernism was resolved. The image that triggered his unique approach was the façade of Calendario’s 14th century Doge’s Palace, with its layering, its combination of straight lines, bold curves, shadow-play and textures. That one example was enough: from it he invoked a new architectural pleasure principle which broke the yoke of tightly ordered modernist design. His powerful fusion of the formal and the lyrical paved the way for the more corporatised sensualism of modernist architects such as Eero Saarinen.

Niemeyer’s injection of the baroque into otherwise obviously modernist structures – his big curves, gracefully modulated ferroconcrete screens, glassy boxes inside beautiful, slim-sectioned outer envelopes – advertised the duality at the heart of his creativity. A lifelong communist and vocal ally of Fidel Castro, he believed in an architecture for the masses, but only if it was physically inspirational evidence of individual aspiration. He said that when triggered by a project he was invaded by his artistic “other”, a persona who dreamed not of the glorious legacy of the Bauhaus but solely of beauty and pleasure; an echo, perhaps, of Corb’s recognition of the “distance and mystery” of architecture.

There was certainly a self-consciously created distance and mystery to Niemeyer’s life, a self-mythologising streak that he shared with other great architects. At a party at Lord Rogers’ London home to celebrate the Brazilian’s Serpentine Gallery pavilion, this mystique was ascribed to “the Paris thing” by the architectural commentator, Charles Jencks. It was in Paris in the late ’60s, after exiling himself from Brazil following his marginalisation as a communist, that Niemeyer found intellectual justification for a pathological pessimism that yet contained a longing for untrammelled humanity, invention, beauty – and conversations with Jean Genet and Jean-Paul Sartre.

The European sojourn allowed Niemeyer to design buildings in France, Algeria, Lebanon, Israel and Madeira, and produced some of his greatest work, notably buildings on the Constantine University campus in Algeria, and the Milan headquarters of the publishers, Mondadori. The former produced a ravishing architectural minimalism; the latter restated the bold gesture and scale of Brasilia’s key buildings, but added asymmetry to wonderful effect. Yet, like Wright, Corb and van der Rohe, the greatness of this mature work was clearly prefigured. Wright’s first domestic buildings in Oak Park, Chicago, were minor masterpieces; Niemeyer’s yacht club and church at Pampulha sent the same kind of electrifying signal of greatness and originality in 1940.

The Brazilian’s architectural legacy remains potent, even in the face of the third millennium’s craving for self-consciously deconstructivist architectural collage. In Brasilia, to enter the radial structure of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Apparition, or to wander through the Palace of the Dawn, is still a riveting experience. The Niteroi Museum of Contemporary Art, Niemeyer’s favourite building, packs the same shock-of-the-new graphic punch that put it in a class of two, with Wright’s Solomon Guggenheim Museum in New York.

The brilliance was not unremitting. Apart from the cathedral and the svelte “flying saucer” at Niteroi, Niemeyer struggled with buildings that were circular in plan: his corporate building in Brasilia and the Parliament of Latin America in Sao Paulo are utterly stolid. It’s also notable that the sense of insouciant sculptural movement that informed the architect’s best work was missing in some of his actual sculptures. The Pantheon of Freedom and Democracy tableau in Brasilia, for example, signally fails to engage.

Niemeyer remained hypnotically engaging, passionate, and acutely interested in attractive women. At his lunch table in 2003 I listened to him, at the age of 95, seethe with an almost Brandoesque intensity against the presence of American troops in the north-west of Brazil. With a deadly froideur he referred to President George W Bush as an unintelligent “son of a bitch”. Niemeyer’s intransigent political commitment, his bi-polar addictions to both beauty and hopelessness, and his hermetic existence in Rio, prevented him from becoming truly world famous.

“For architects schooled in the mainstream Modern Movement,” said Lord Foster when the Brazilian – in ambulophobic absentia, as usual – received the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Gold Medal in 1998, “Oscar Niemeyer stood accepted wisdom on its head. Inverting the familiar dictum, form follows function, Niemeyer demonstrated instead that, when a form creates beauty it becomes functional and, therefore, fundamental in architecture. Few architects in recent history have been able to summon such a vibrant vocabulary, and structure it into such a brilliantly communicative and seductive tectonic language.”

Oscar Niemeyer’s buildings provide monumental evidence of a monumental architectural talent. Niemeyer himself will remain a rather fugitive, tender, presence; a man who liked to recall the old gardens of Rio, or the Grand Hotel in Belo Horizonte, where he loved eating in its glass-domed restaurant. “Today is a Sunday of rain and solitude,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I am alone at the office, tired of life, tired of this obstacle course of tears and laughter ... I cannot help crying, quietly, slowly, tenderly, with melancholy.” How strange it was, and yet how obdurately optimistic, that so much beauty flowed from this great, and absolutely unique, architectural Diogenes.

Oscar Soares Filho Niemeyer, architect: born Rio de Janeiro 15 December 1907; married Anita (one daughter); died Rio de Janeiro 5 December 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments