Nicanor Parra: Chilean physicist who became the father of ‘anti-poetry’

His first book in 1954 was one of the most influential collections of Spanish verse of the 20th century and a major source of inspiration for Beat Generation writers such as Allen Ginsberg

Nicanor Parra was the Chilean scientist-turned-poet who revolutionised Latin American verse by rejecting its flowery diction and forging a stripped-down, confrontational and darkly comic form that he dubbed “anti-poetry”.

Chilean President Michelle Bachelet hailed Parr as “one of the biggest authors of our literature, in our history.” His blunt, subversive and playful work influenced writers ranging from Thomas Merton to the Beat poets to Pablo Neruda, wowing literary critics along the way. One of them, Yale University professor Harold Bloom, called Parra as “essential” as Walt Whitman. In 2011, Parra was awarded the Cervantes Prize, the Spanish-speaking world’s highest literary honour.

Parra’s poetic gate-crashing was partly inspired by the long shadow of Neruda, a Nobel laureate and fellow Chilean with a global following. Parra made it his life’s mission to bring such exalted wordsmiths and poetry itself “down from Olympus” and make them accessible to regular people.

His work had a liberating effect, especially in Latin America, where since the 1930s poets had favoured Wagnerian language, romantic yearnings and heroic gestures. By contrast, Parra preferred street argot and dwelt on the small frustrations of put-upon office workers, alienated students, bag ladies and thugs. His blunt style and bleak outlook were influenced by the precise formulas and rational theorems of science as well as by the nightmarish visions of Franz Kafka and TS Eliot.

The result was an outpouring of “anti-poems” about an off-kilter world in which love begets exploitation, sex becomes torture and miscommunication reigns. They often feature lost souls unable to connect with other people as their minds wander from the heads of lettuce in the kitchen to concerns about the reproduction of spiders.

Humour was key.

In “Help”, the joyous narrator chases a phosphorescent butterfly only to see pastoral bliss dissolve as he trips and smashes his face into the ground. He ends with a plea:

Save me once and for all

Or shoot me in the back of the neck.

In “Lullabaloo”, an angel tries to shake the hand of the narrator, who responds by grabbing the angel’s foot and ruffling his feathers. Enraged, the angel swipes at him with a sword, but the narrator ducks, then bids a sarcastic farewell:

Be on your way.

Have a nice day

Get run over by a car,

Get killed by a train.

Parra once explained: “I think that the poet should be a specialist in communication. Humour makes contact [with the reader] easier. Remember that it’s when you lose your sense of humour that you begin to reach for your pistol.”

Uruguayan-born literary critic and Yale professor Emir Rodríguez Monegal wrote that “by interrupting and even cutting short the anecdotal flow, Parra ‘deconstructs’ the poem and finally achieves an almost epigrammatic structure”.

Another noted scholar of Latin American verse, Alexander Coleman, wrote in The New York Times in 1972: “Make no mistake: Nicanor Parra is a poet (or an anti-poet or whatever) of total command and total grandeur.”

Others were repulsed. A handful of translators in the US refused to touch his work, which they viewed as vulgar and sacrilegious. Commenting on Parra’s 1962 collection Salon Verses, Prudencio de Salvatierra, a prominent Chilean-born Franciscan priest, author and literary critic, wrote: “In this work there is complete contempt for women, religion, virtue and beauty. I have been asked if this book is immoral. I would say no; it is too filthy to be immoral. A can of garbage is not immoral, no matter how many times we stir up its contents.”

Parra’s work was so incendiary that, despite his stature as one of the world’s leading experts in Newtonian physics, he was far better known for his writings.

Neruda, who helped him find a publisher for his ground-breaking 1948 collection Poems and Antipoems, adopted some of Parra’s techniques. Devotees included Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, whose City Lights Books first published Parra’s work in the US. Alluding to Parra’s eruptive techniques, Merton labelled him “the poet of the sneeze”. When Parra was awarded the Cervantes Prize, Cervantes Institute director Víctor García de la Concha described the Chilean writer as “a poetic sniper who revitalises everything”.

Parra was dubious about fame and sparred with journalists, turning interviews into “anti-interviews”.

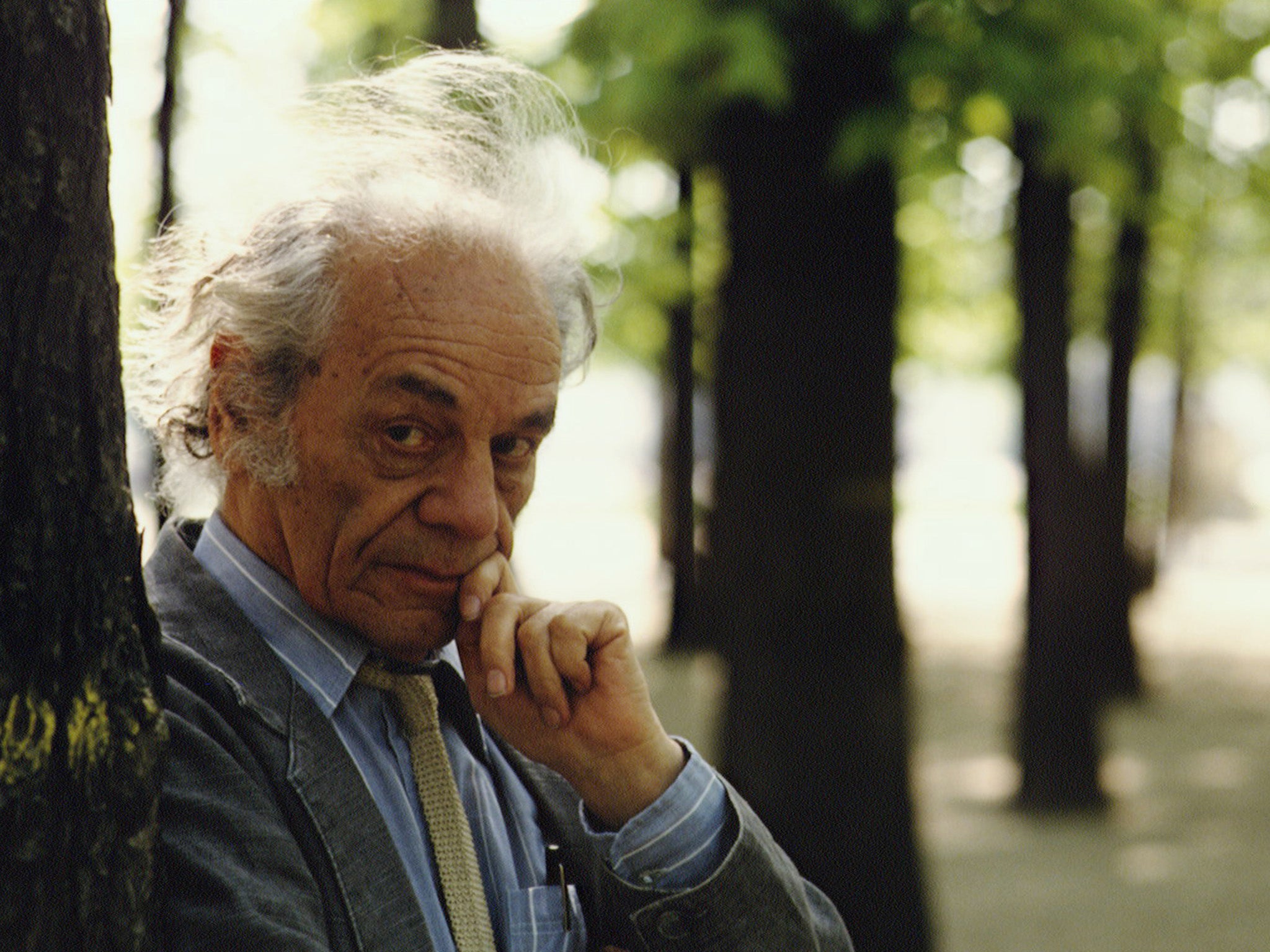

An arresting presence at readings with his fierce eyebrows, long sideburns and Einsteinian splay of white hair, Parra would jar audiences by calling his efforts a total failure and signing off with the declaration: “I take back everything I’ve told you.”

His helter-skelter love life included numerous affairs with much younger women, including his housekeeper, art students, fans and hippies whom he would sometimes entrance with verses made up on the spot.

His politics were also fickle. An early environmentalist, Parra in one poem speaks in the voice of God, warning: “If you destroy the Earth, don’t think I’ll create it again.”

In 1963, he spent six months in the Soviet Union translating into Spanish the work of several of the country’s poets. But he refused to join Chile’s Communist Party.

In 1970, with the Vietnam War still raging, he was photographed taking tea at the White House with First Lady Pat Nixon. That prompted the Cuban government under Fidel Castro to rescind Parra’s invitation to serve as a judge at a prestigious book fair in Havana.

Leftists were also enraged by his 1972 publication Artifacts, a collection of short poems and drawings in which he poked fun at the socialist government of Chilean President Salvador Allende.

After Allende committed suicide during a 1973 military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet, Parra refused to join the exodus of artists fleeing the country. Though he mostly avoided politics, some of the poems in his 1977 collection The Sermons and Teachings of the Christ of Elqui take aim at the Pinochet regime’s human rights abuses.

Parra came to view all government as a form of dictatorship. Public Works, his 2006 multimedia exhibition in Santiago, included cut-outs of all Chile’s presidents hanging by their necks.

It caused an uproar. But throughout his career Parra warned people to approach his work at their own risk, a stance he summed up in “The Solemn Fool”:

For half a century

Poetry was the paradise

Of the solemn fool.

Until I came

And built my roller coaster.

Go up, if you feel like it.

I’m not responsible if you come down

With your mouth and nose bleeding.

Nicanor Segundo Parra Sandoval was born in San Fabián de Alico, a village in southern Chile in the year the First World War started. His family lived on the edge of poverty, but his school teacher father and seamstress mother promoted arts and culture among their eight children. Parra’s younger sister, Violeta, was one of Chile’s best-known folk singers and penned the classic “Gracias a la vida” (“Thanks to life”) before killing herself in 1967.

Parra won a scholarship to a prestigious Santiago high school and graduated from the University of Chile in 1938 with degrees in mathematics and physics. He studied advanced mechanics at Brown University in Rhode Island and cosmology at the University of Oxford in England and was a visiting professor at American universities, including Columbia and Yale. He taught theoretical physics at the University of Chile from 1948 until retiring in 1991.

But from the beginning, Parra felt the literary tug. In 1969, he won Chile’s National Literary Prize and, three years later, was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship. He once stated that he taught physics to earn a living but wrote poetry to stay alive.

His marriages to Ana Delia Troncoso, with whom he had three children including the visual artist Catalina Parra, and to a Swedish woman, Inga Palmen, ended in divorce. He had a son with his housekeeper, Rosita Muñoz, and two more with painter Nury Tuca, who was 33 years his junior. A complete list of survivors could not immediately be determined.

In contemplating death and his controversial legacy, Parra created a piece of anti-poetry in 1954 called “Epitaph”:

Neither too bright nor totally stupid,

I was what I was: a mixture

Of vinegar and olive oil,

A sausage of angel and beast!

Nicanor Parra, physicist and poet, born 5 September 1914, died 23 January 2018

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies