Mike Terry: Campaigner who led the Anti-Apartheid Movement for two decades

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

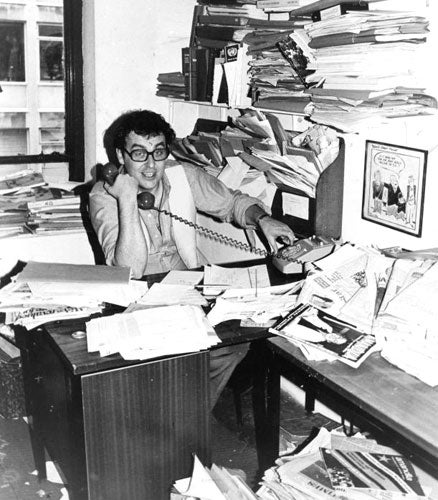

Your support makes all the difference.As Executive Secretary of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, Mike Terry played an important role in turning the tide of British and international opinion against South Africa's racially segregated regime. He led the organisation through two decades of campaigning and lobbying, until it was disbanded in 1994, when elections brought Nelson Mandela to the presidency of a new, post-apartheid South Africa.

Born in London in 1947, Terry began his involvement with southern Africa as a young teacher in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1966, the year after the Unilateral Declaration of Independence by the Ian Smith government. He studied nuclear physics at Birmingham University, where he was president of the Student Union in 1969 – the year of the anti-apartheid demonstrations at Twickenham against the Springboks rugby tour. He went on to become secretary of the National Union of Students, and then worked for two years for the International Defence and Aid Fund.

In 1975 Terry joined the Anti-Apartheid Movement as Executive Secretary. The organisation had been formed in London in 1959, as a "boycott committee" to draw attention to the evils of apartheid. Julius Nyerere addressed the first meeting, along with Trevor Huddleston, later president of the AAM. As the years passed, the movement's main objective was to campaign for a democratic South Africa where every section of society had equal voting rights. It seemed at the time that the apartheid regime was impregnable since it had the support of Western governments, South Africa having played the card that it was a bastion of the free world in the fight against Soviet expansionism.

Maintaining close links with the African National Congress, the AAM evolved policies to isolate South Africa, advocating economic, diplomatic and sporting sanctions, and no military or nuclear collaboration with the country. It is difficult to imagine the initial and lingering hostility to these policies, especially in the present climate of international relations where the application of sanctions is the weapon of first resort in dealing with a "rogue" state.

There is evidence that the movement was under attack from the South African Bureau of State Security (BOSS) and we were certain that phone lines were regularly tapped. For those who worked for AAM life was never free from danger. On one occasion the organisation's offices, in Camden, north London, were fire bombed and would have been razed to the ground but for a local resident who spotted the glow while taking his dog for a late-night walk.

We had many political discussions, arguments and even flaming rows in AAM, which was hardly surprising given that the membership came from people of such diverse views (although from predominantly Labour circles).

Terry was the secretary of Freedom Productions, the company set up by AAM to organise the two Wembley Stadium concerts in support of Nelson Mandela. The first, in 1988, pressed for Mandela's release from prison and was timed to mark his 70th birthday. The second, in April 1990, was attended by Mandela himself, two months after he had walked free after 27 years in jail. Both were broadcast by the BBC around the world, with profits going to children's charities in Africa.

During the period when Terry was in charge, the Anti-Apartheid Movement grew in influence and size, especially following the Soweto massacre of 1976 and after the Mandela concerts. The membership increased from 2,500 in 1984 to 20,000 in 1989, with 1,300 affiliated organisations. Terry would never claim that the increase in activities and campaigns was all his own doing, but he is due considerable credit for his immense hard work and application. He managed to combine principles with pragmatism and impressed everyone with his commitment and integrity.

Terry continued as executive secretary until 1994. The release of Mandela and the other political prisoners from Robben Island had paved the way for the first free elections. As it became clear that a democratic South Africa was inevitable, Terry put his mindto what the future should hold for the movement. He set out to the executive committee what the choices were: either to close down AAM and accept that its work was done or find away for the organisation to play aconstructive role in the future of southern Africa.

He persuaded the executive to seek the views of the membership. More than 90 per cent said they wished to remain involved in work for Southern Africa – although the number of different suggestions as to what this might entail was almost equal to the number of members. Finally, as a result of the consultations, Action for Southern Africa (Actsa) came into being, to campaign for peace, democracy and development across the region.

It was a surprise to many that Terry did not apply to be the first Director of Actsa. But he had decided that new ideas and methods of working were required for promoting freedom in South Africa, and it would no longer be an organisation of protest. The defining factor in deciding his future was his passion for teaching, a commitment he had put behind him for two decades. So he went back to university to brush up on his physics and train to be a teacher.

Working at Alexandra Park School in Haringey, north London, Terrycontinued to support the new South Africa and to promote the values he cared so deeply about to a new generation. He was a great believer inscience as a medium for enhancing students, especially those in developing countries. He was instrumental in establishing the Oliver Tambo Science Student of the Year Award, as well as the partnership between Alexandra Park School and Ephes MamkeliSecondary School in Wattville, the East Rand township where Oliver Tambo is buried.

Terry initiated the placing of a historic plaque at the house in Haringey where the Tambo family lived during 30 years of exile, and the creation of a memorial garden and bust of Tambo in the Albert Road Recreation Ground in the borough. In 2001 Terry was appointed OBE for his contribution to the Anti-Apartheid Movement.

Terry leaves his partner, Monica Shama, and a son, Andrew, from a previous relationship. For all his seriousness, Terry was an engaging companion with a lively sense of humour and I enjoyed his company when we travelled together and met at social occasions. The last time I saw him was in June at the Hyde Park concert for Nelson Mandela's 90th birthday, where he was in splendid form and discussed with Madiba what might be done to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the founding of AAM in June 2009.

We shall now have to mark this occasion without him. Next year will be a celebration of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, but it will also be a celebration of the life and work of Mike Terry.

Bob Hughes

Michael Denis Alastair Terry, teacher and anti-apartheid campaigner: born London 17 October 1947; one son; died London 2 December 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments