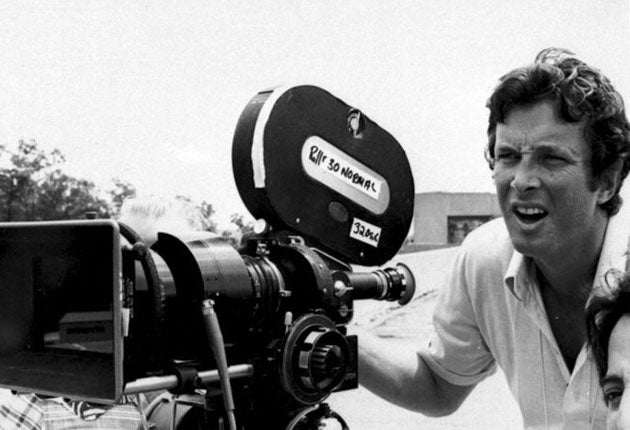

Michael Crichton: Bestselling novelist, film director and screenwriter whose creations included 'Jurassic Park' and 'ER'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.First and last the novelist, scriptwriter, movie director, pulp-fictioneer and medic Michael Crichton wrote to entertain. In this he was spectacularly successful, his most celebrated creation, Jurassic Park – the tale of dinosaurs running amok in the 20th century – transformed him into a wealthy man. At his best he mixed fable with what seemed like state-of-the-art hard science and like all great story-tellers – or fabulists – he made his readers believe in just about everything he wrote. Those readers devoured his books, which sold well over 150 million copies throughout the world, and were translated into more than 30 languages.

He also wrote to inform, to educate, sometimes to proselytise, and latterly, towards the end of his life, he wrote angrily, to accuse. But even at his most stubbornly, obsessively denunciatory – global warming as a scientific conspiracy (State of Fear, 2004); emancipated females have become too powerful (Disclosure, 1994) – he still exhibited tremendous narrational flair. Page after page always had to be turned.

Crichton was a master of the "big idea", especially the big scientific or technological idea which goes catastrophically and spectacularly wrong. His first book under his own name (preceded by a number of pseudonymous thrillers), The Andromeda Strain (1969) told of the consequences of an unmanned research satellite returning to Earth lethally contaminated by a virus that could wipe out mankind. It became a global bestseller (although Nigel Kneale had come up with the plot-line back in the 1950s with The Quatermass Experiment), and tapped into the secret fears of readers convinced that scientists will in the end destroy us all; the book was made into a hugely successful movie, in 1970, directed by Robert Wise.

This notion was subscribed to by Crichton himself, never happier, seemingly, than when writing of scientific blunders that threaten the human race. In The Terminal Man (1972), the brain of a violent criminal is linked to a computer, via "psychosurgery", to cure him, but instead it turns him into a berserk monster. The chilling Binary (1972, the last of his pseudonymous thrillers) tells of the theft of a half ton of deadly nerve gas by a mad millionaire intent on wiping out San Diego. In Prey (2002), lab-created molecular beings turn against their creators.

Crichton seemed to soak up science like a sponge, refining it, and utilising it to its best advantage cloaked in a thrilling plot. Yet one of his simplest ideas was transformed into a wildly successful franchise when he created the TV series ER in 1994, which for all its sophistication and brilliance was at heart an old-fashionable hospital drama. Yet such were his story-telling and editorial skills that over the years he won an Emmy, a Peabody, and a Writers' Guild of America award for the show. Many of his novels were turned into movies, often with Crichton himself as screenwriter and director.

Jurassic Park (1993, from his 1990 novel) is probably his finest "high concept" creation, and certainly the film for which he'll best be remembered. A clever twist on Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World, it presented a bizarre scientific idea – extinct creatures' DNA used to create living dinosaurs in the 20th century who inhabited an island theme park – as scientific fact. Real scientists dismissed the notion, but Crichton could always be immensely persuasive, and once the idea is accepted – or at any rate disbelief is willingly suspended – the viewer is off on a rollercoaster ride of escalating thrills. Until the inevitable malfunction (to be found in nearly all of Crichton's novels) throws the on-screen adventurers into real and horrifying peril.

With the help of judicious dollops of CGI, Jurassic Park became a franchise; the Steven Spielburg-directed original, which grossed $900m worldwide, was followed in 1997 by The Lost World: Jurassic Park, based on Crichton's 1995 novel. Jurassic Park III followed in 2001, with a fourth helping in the pipeline.

Crichton's narrative skills were evident from the start of his writing career. "The dynamite, neatly bundled in 'Happy Birthday' wrapping paper, lay casually on the back seat." This beautifully executed "hook" – why is the dynamite wrapped in gift-paper, what'll it be used for, what's going on? – is the first line of his very first book, Odds On (1966). Written under the pseudonym "John Lange" (in his early days Crichton, 6'9" and gangly, liked a joke: "lange" is German for tall), it was the first in a series of tautly plotted, pacy paperback originals he wrote to see himself through Harvard Medical School, from which he emerged as a fully fledged MD in 1969.

By then, however, it was clear that he wanted to write rather more than he wanted to follow a medical career, since his medical thriller, A Case of Need (1968) – in which a doctor, trying to discover who was responsible for the death of a teenage girl in a big-city hospital, uncovers a web of corruption – won that year's Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for best novel. A Case of Need, Crichton's first outing in hard-covers, was written as "Jeffery Hudson" (another joke: the original Hudson was a dwarf court jester at the time of Charles II).

John Michael Crichton was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1942. Growing up in Roslyn, Long Island, he graduated summa cum laude from Harvard, gaining a degree in Anthropology (1964). He resided briefly in England, teaching Anthropology at Cambridge University, then joined Harvard Medical School, qualifying in 1969. He then became a postdoctoral fellow at the Salk Institute, in La Jolla, California.

After his thriller-writing success, Crichton tried his hand at directing a made-for-TV mystery called Pursuit (1972). He was so taken with this new mode of storytelling that he produced a script about a luxury resort where clients can indulge their wildest fantasies for $1,000 a day – in the world of medieval jousting and romance, the decadent and luxurious Roman Empire, or the world of the old West, all served by lifelike robots, but where a computer virus sends all the automata into a murderous frenzy. This was Westworld (1973, starring Yul Brynner).

The film was a success, though the making of it was a nightmare, with budgets cut on an almost weekly basis, Crichton's screenplay constantly revised (then denounced by studio executives, then cut, then added to), and the entire project, for which Crichton was also director, cancelled at least twice. Yet the finished product turned out to be a brilliant piece of nail-biting pulp fiction, certainly on a par with other "pure entertainment" movies such as John Carpenter's Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), Escape from New York (1981), and Walter Hill's The Warriors (1979).

A rare failure was the novel The Great Train Robbery (1975), based on the real-life theft of bullion from the South Eastern Railway in England in 1856. For once Crichton over researched, his characters all speaking in correct Victorian villain's lingo – which was virtually incomprehensible to the reader. The 1978 film fared better.

Crichton did not entirely restrict himself to fiction, winning an Association of American Medical Writers Award for Five Patients: the hospital explained (1970), based on his own medical experiences. He also wrote a book on computers, Electronic Life (1983), and an acclaimed biography of the artist Jasper Johns (1977).

In his fictional writing, in the main, he liked to recreate myths in a contemporary setting. His novel Congo (1980, film 1995), about a gigantic ape in Africa, is basically King Kong crossed with Ryder Haggard for the modern reader, and none the worse for that. In so many of his thrillers, the big scientific idea is expertly linked to one of the oldest and most basic myths of all, that of the genie escaping from the bottle and wreaking terrible havoc.

Jack Adrian

John Michael Crichton, novelist, screenwriter and film director: born Chicago 23 October 1942; married 1965 Joan Radam (marriage dissolved 1970), 1978 Kathy St Johns (marriage dissolved 1980), thirdly Suzanna Childs (marriage dissolved), 1987 Anne-Marie Martin (one daughter; marriage dissolved), 2005 Sherri Alexander; died Los Angeles 4 November 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments