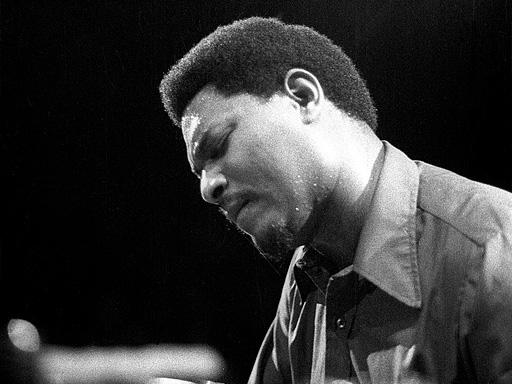

McCoy Tyner: Titan of jazz piano who helped to propel the John Coltrane Quartet

He was regarded as one of the most influential players of his generation

McCoy Tyner’s performances with John Coltrane’s groundbreaking quartet of the 1960s and on dozens of his recordings made him one of the most influential jazz pianists of his generation.

His approach to the piano combined robust chords with delicate melodic improvisation. In 1960, he joined forces with Coltrane, a saxophonist he had known while growing up in Philadelphia. Tyner, who has died aged 81, was the last surviving member of what jazz fans call the “classic quartet”, which included the bassist Jimmy Garrison and the drummer Elvin Jones.

During his five years with Coltrane, Tyner performed on several albums that have become jazz landmarks, including My Favorite Things, Crescent, Impressions and A Love Supreme.

“Even though John was, so to speak, the engineer of the train, each of us had to fashion his own concept,” Tyner said in 1979. “The stimulation was mutual; while we always felt the strength of John’s presence, he told us that what he played was a reaction to what was happening around him.”

A Love Supreme, a four-part suite conceived by Coltrane but largely improvised in the studio by the quartet, became one of the most revered albums in the jazz canon. It was recorded on 9 December 1964, two days before Tyner’s 26th birthday, and came to be seen as a musical expression that approached an almost trancelike state of spiritual release.

Throughout the recording, the shifting chords of Tyner’s piano provide a foundation for Coltrane’s driving tenor saxophone lines. At various times, Tyner takes over with confident, fleet-fingered solos that push Coltrane to ever more intense musical heights.

In the final movement, “Psalm”, Jones creates an ominous sonic cloudburst on drums as Tyner plays clanging chords and Coltrane seeks a path towards musical resolution.

One of Tyner’s most sensitive extended performances came in John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, a 1963 album that was Coltrane’s sole recording with a singer. Coltrane plays with considerable restraint on the album, consisting mostly of ballads, as Tyner steps forward with delicate solos and harmonic patterns that balance Hartman’s velvety vocals.

Tyner left Coltrane’s group in 1965, becoming uneasy with the increasingly atonal and noisy direction of the saxophonist’s music. “He had two drummers at that time,” Tyner said in 1976, “and I couldn’t hear what I was doing.”

By then, he was already writing and recording music of his own, beginning with the 1962 album Inception. In 1967 Tyner released the album The Real McCoy, featuring three of his compositions that became jazz standards, “Passion Dance”, “Search for Peace” and “Blues on the Corner”.

During the 1970s, when other jazz musicians were turning towards electronic instruments and funkier styles of music, Tyner adamantly stuck with the acoustic piano, calling it an extension of himself. He often recorded several albums a year, repeatedly won critics’ polls and became recognised, as the critic Leonard Feather wrote in the Los Angeles Times, as “the most influential pianist of his generation”.

In 1988, Tyner won the first of his five Grammy awards. He recorded with various instrumentalists, including on a graceful 1990 collaboration, One on One, with the late French jazz violinist Stephane Grappelli. Tyner’s other albums included solo performances, big-band recordings and excursions into Latin music.

Alfred McCoy Tyner was born in 1938, in Philadelphia. His father was a factory worker, his mother a beautician. Tyner began piano lessons at 13, and soon afterwards his mother put a piano in her beauty salon.

“The saxophone player was next to the [hair] dryer,” Tyner recalled, “and the drummer was next to the shampoo chair. Those women heard some rocking tunes when they got their hair fixed.”

He grew up with several other prominent Philadelphia jazz musicians, including the pianist Bobby Timmons, the trumpeter Lee Morgan and the saxophonist Archie Shepp. Bud Powell, the pre-eminent bebop pianist of the 1940s and 1950s, sometimes practised on the Tyner family piano.

Tyner was 17 when he met Coltrane, who grew up in Philadelphia and shared North Carolina roots with the Tyner family.

“We were very close. He was like a big brother to me,” Tyner said in 1993. “We just had a similar perspective on music. It wasn’t a thing you could verbalise.”

In 1959, Tyner joined the Jazztet, a group jointly led by the trumpeter Art Farmer and the saxophonist Benny Golson. The next year, he was featured on Golson’s jazz standard “Killer Joe” before he left for Coltrane’s quartet.

Tyner continued to perform in concerts and international festivals into his late seventies, but he considered his time with Coltrane, who died in 1967, the highlight of his career.

His marriage to Aisha Saud ended in divorce. He is survived by three sons.

McCoy Tyner, musician, born 11 December 1938, died 6 March 2020

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies