Matt Yuricich: Visual effects artist who won an Oscar for 'Logan's Run'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Working on more than 200 films from the 1950s through to the 1980s, Matt Yuricich was one Hollywood's finest and most prolific visual effects artists, specialising in matte painting on glass to create the dramatic backdrops for live action scenes in the days before CGI. He was one of the last surviving matte artists of the Golden Era of Hollywood but gained international recognition only in 1976 when he won a Special Achievement Oscar for his art on the futuristic movie Logan's Run.

Yuricich and his team created the 23rd-century dome-enclosed city which stole the show while Michael York's 29-year-old character Logan tried to escape an ageist society where death by the age of 30 was obligatory. Accepting the Oscar from the actor Roy Scheider, Yuricich famously told the Academy, and the world, after thanking his wife Clotilde: "... and I'd like to thank myself. I think I deserve it."

Yuricich, of Croatian origin, was also an Academy Award nominee for his work on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and the futuristic backdrops which gave a unique ambience to Bladerunner (1982). He was part of the visual effects teams nominated for Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) and Steven Spielberg's 1941 (released in 1979 and beaten in the visual effects category by Ridley Scott's Alien). You may hardly have noticed it – you were not meant to, the overall effect is meant to be seamless – but Yuricich's glass-painted backdrops featured in such box office successes as Ben-Hur (1959, including the chariot race), Hitchcock's North by Northwest (1959, in which Yuricich created the external views of the James Mason character 's famous modernist house on Mount Rushmore), The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), Young Frankenstein (1974, notably the spooky castle), the Planet of the Apes series in the 1970s), China Syndrome (1978), Ghostbusters (1984), Die Hard (1988), Dances with Wolves (1990) and Field of Dreams (1989, in which he helped to create the illusion of a baseball stadium emerging from a cornfield).

Before computer enhancement made it easier, though perhaps no less creative, matte painting was a backbone of movie-making, saving many thousands of dollars, even millions, in location costs. Why should Hitchcock have a Frank Lloyd Wright-style house built on top of Mount Rushmore for North by Northwest? He tried but wasn't allowed to, but he could build a mock-up in the studio and have someone like Yuricich paint an external view of one.

In Ben-Hur, although almost 8,000 extras were used, Yuricich made them look like tens of thousands through his matte paintings, creating the illusion of Rome's vias stretching for miles to the mountains, which he also painted. His peers called Yuricich's work "money shots," which helped give the movie its grand scale despite being shot in studios or back lots. Whether in Ben-Hur, or in Ghostbusters, Yuricich had to match his matte paintings to scale according to the lens and film being used. He would paint his backdrop leaving a space in the glass where the live action would be superimposed but soon found that wind or other elements on location could put the whole thing out of synch. "We had to take out that movement frame by frame and plot it," he recalled of Ben-Hur. "Then when we photographed the painting, we had to move it to those corresponding numbers, vertically and horizontally, for each frame. They save a thousand dollars not having anyone on location, and spend a hundred thousand dollars trying to fix it at the other end (post-production)."

Recognition for Yuricich and his fellow matte artists came slowly – in his case, more than halfway through his career – largely due to the fact that the old-fashioned studio bosses deliberately tried to conceal the trickery that brought magic to the Silver Screen.

Matthew John Juricic (US Customs changed the spelling when his parents arrived as immigrants at Ellis Island, New York) was born in the small town of Lorain, Ohio, on Lake Eerie west of Cleveland, in 1923, one of six siblings. Seeking work, and peace, his parents Anthony and Anna Yuricich (née Plesivac) had fled the turmoil in Croatia, at the time part of the uneasy kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes later to be renamed Yugoslavia. When young Matthew started school, he spoke no English, only Serbo-Croat, but graduated from High School in 1941 and joined the US Navy the following July. While training in California he met the actress and wartime forces' pin-up girl Betty Grable, and they became close friends before he set sail for the South Pacific as an Ordnanceman First Class aboard the aircraft carrier USS Nassau. His job was to load the guns, bombs and ammunition on the carriers' warplanes before their raids to support Marines fighting the Japanese on the islands. After leaving the Navy in December 1945, he wrote that the Battles of Tarawa in November 1943 and of Kwajalein in January/February 1944, were "forever etched in my mind."

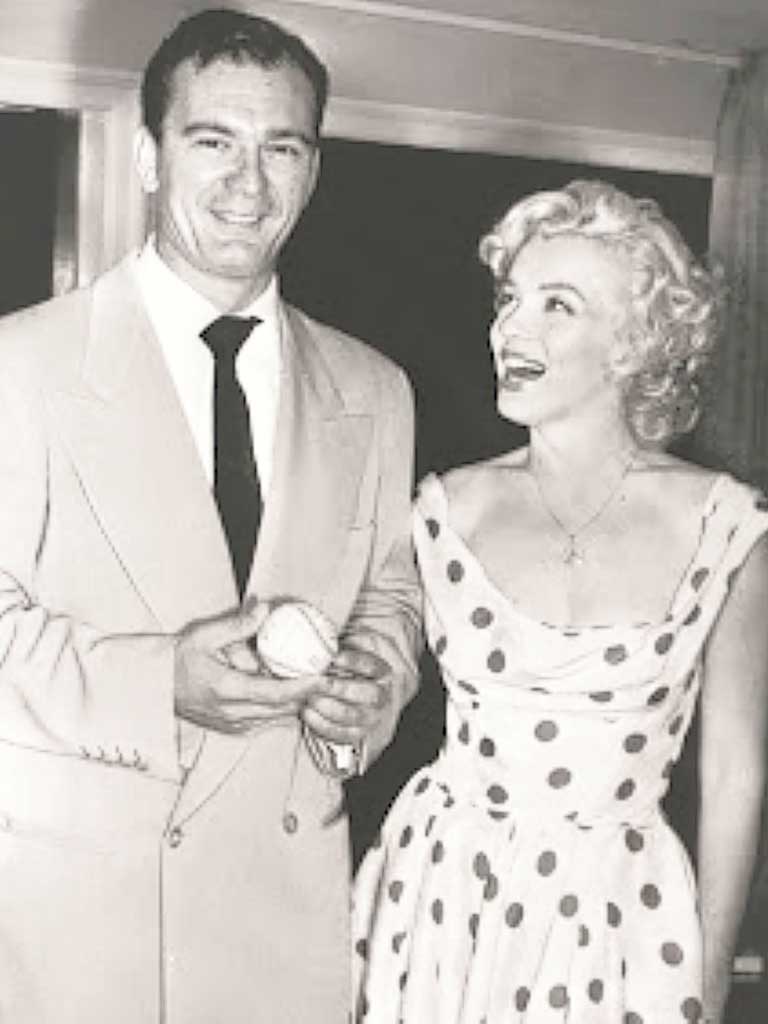

After the war, Yuricich studied Fine Arts at Miami University, starring for the football team – one of the best colleague teams in the country – and graduating in 1950. He was also an avid archer and went on to win several national US titles and set many long-lasting records. After hitchhiking to Los Angeles to see his old friend Betty Grable, who was working at the 20th Century Fox studios, he got a job as an assistant in the renowned Fred Sersen's visual effects department, also meeting Marilyn Monroe and playing in her winning softball team in 1952. He later sent a photograph of himself with Monroe, in a white dress with polka dots, to a protégé of his, Rocco Gioffre, which he signed: "Eat your heart out!"

From Fox, having married his childhood sweetheart Clotilde Robison, a girl of Scottish parentage, Yuricich moved to MGM, where Ben-Hur, with its stunning special effects, was among his first films.

Yuricich formally retired in 1990 to Henderson, Nevada, but continued to do some freelance matte painting work for the Hollywood studios before moving to Washington State to be closer to his children and grandchildren. He died in the Motion Picture Home for ex-Hollywood personnel in Woodland Hills, California. He is survived by his five children and eight grandchildren and his brothers Frank, Joe and Richard, the latter a renowned special effects cinematographer.

Matthew John Juricic (Yuricich), special effects matte artist: born Lorain, Ohio 19 January 1923; married Clotilde Robison (divorced 1976; five children); died Woodland Hills, California 28 May 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments