Mario Monicelli: Director and screenwriter whose comedies exposed immorality and injustice in his native Italy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

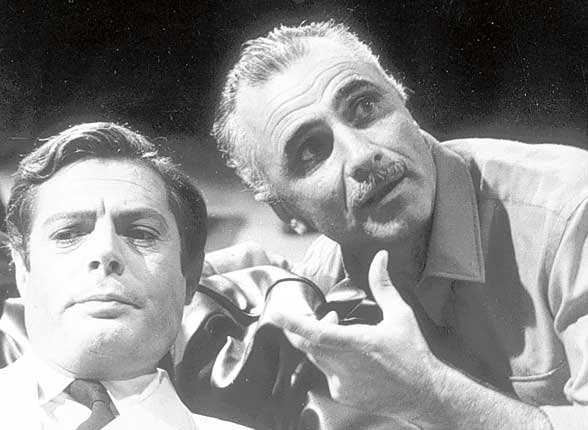

Your support makes all the difference.Mario Monicelli, often called "the father of Italian screen comedy", was one of the Italian cinemas greatest craftsmen, a director whose prolific output (over 70 films) included several masterpieces, such as the superb caper comedy I Soliti Ignoti (1958), and the biting satire La Grande Guerra (1959), which won him Venice's Golden Lion award.

Emerging as a prime force shortly after the end of the Second World War, having spent over a decade as a scriptwriter, he was part of an outstanding upcoming group of directors, including Visconti, Pasolini and Bertolucci. His films were noted for their trenchant exposés of social conditions and lapsed morality while providing much to laugh at. He promoted the careers of Marcello Mastroianni, Vittorio Gassman and Claudia Cardinale, and had rewarding associations with the comic actors, Toto and Alberto Sordi.

Born in 1915 in the coastal town of Viareggio, Tuscany, he was the son of a noted journalist, Tommaso Monicelli, and had two older brothers, one a writer and translator, the other a journalist. (Tommaso was to kill himself in 1946.) After the Universities of Pisa and Milan, where he studied literature and philosophy, he became a film critic and amateur film-maker. At 20 he made a 16mm feature-length film, I Ragazzi della Via Paal, based on a story by Molnar, which won an amateur prize at Venice in 1935. In 1937 he made another amateur feature, Pioggia d'Estate (Summer Rain), then spent 12 years as scriptwriter and assistant director, collaborating on the scripts of some of the most celebrated Italian films of the 1940s, notably DeSica's I Bambini ci guardano (The Children Are Watching Us, 1943) and De Santis' Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice, 1949).

He made his official debut as a director when he collaborated with Steno (real name Stefanio Vanzina) on Toto cerca casa (1949), the first of several popular films the team made starring Toto over the next four years, including Guardie e Ladri (Cops and Robbers, 1951) and Toto e i Re di Roma (1952). Monicelli was already establishing himself as an artist who could blend humour with acute observation and social relevance – Toto cerca casa is a farce, but its background is the desperate housing shortage in Italy at the time, while Guardie e Ladri caused a scandal by suggesting that a thief and a policeman could be friends.

"I was summoned by the Director General of Entertainment since it was considered revolutionary to show that it was possible for a policeman and a thief to share common problems," Monicelli recalled. "They helped each other out and, in the end, when the thief was taken to prison, he reminded the policeman to take care of his family for him. Putting these two people on the same level seemed revolutionary, as if the foundations of Italian society had been shaken. We have to remember that five years earlier, Italy was still under fascism."

Monicelli worked as a solo director from 1954, starting with a rare drama, Proibito. "It was an experiment which confirmed to me that it wasn't in my nature to express things only in a dramatic way. I like saying things a little tongue-in-cheek, or at least with a satirical intention and a desire to ridicule, even combine farce with tragedy."

He found himself in trouble with the censors again when Toto e Carolina (1955), which depicted a young suicidal girl being helped by Communists, was banned for a year and a half, then released with 34 cuts. Monicelli told the historian Jean A Gill, "The government, the carabinieri, the police force, were absolutely off limits. It was a continuous battle. Fortunately we pushed – not just Steno and myself but all of the Italian film world, so that things would become more transparent.'

Monicelli had his first international hit with the comedy I Soliti Ignoti (1958), sometimes called Italian cinema's first true commedia all'italiana. I can still remember the gales of laughter that greeted the exploits of its inept band of thieves when the film was shown at London's Academy cinema. Toto was fine as ever, but the film also gave early comedy roles to Marcello Mastroianni, Vittorio Gassman and Claudia Cardinale. Like most Monicelli films, it had a bitter edge and no cosy ending, but it was fine entertainment. Given the title Persons Unknown in the UK, it was re-titled Big Deal on Madonna Street in the US, where it was an enormous hit. It was poorly remade by Louis Malle as Crackers in 1984 and turned into a Broadway musical, Big Deal, by Bob Fosse in 1986. Monicelli's collaborators on the story and script were Agenore Incrocci (called Age) and Furio Scarpelli, and they remained with him for most of his career.

Monicelli next made one of his bravest and most controversial films, the funny but painfully evocative La Grande Guerra (The Great War, 1959), a scathing satire of the First World War with Alberto Sordi and Vittorio Gassman as peasants thrust into the bewildering world of battle. "Even before shooting commenced there was a campaign against the film," he said. "The newspapers published articles saying the film should be banned: 'These people will only defile the memory of the 600,000 who died in World War l.' Once the film was released, it was total rapture. A film could finally say that these men had gone to war without knowing why. They were poor devils, badly dressed, badly fed, ignorant, illiterate, who had gone to do a job that had nothing to do with them." The film won the Golden Lion award at Venice, and was nominated for an Oscar as best foreign film.

Reflecting the director's political views, many of his films promoted opposition to injustice and the arrogance of people in power, and in 1963 he made a film about strikes over workers' conditions in Turin at the turn of the century, I Compagni (The Organizer, 1963), but despite Mastroianni in the title role, positive reviews and a second Oscar nomination for the director, it was not popular. He had more success with L'armata Brancaleone (For Love and Gold, 1965), a comedy that took a neo-realistic approach to its portrait of the Middle Ages in its depiction of the escapades of a poor but pompous knight (Vittorio Gassman). Its success spawned a sequel, Brancaleone alla Crociate (Brancaleone at the Crusades, 1970), which Monicelli first resisted: "It's not good to make sequels. After years, I finally gave in when I thought I might be able to express different things." The film was popular, however.

In 1968 he received another Oscar nomination, for La Ragazza con la pistola (Girl with the Gun), which starred Monica Vitti as a girl who travels from Sicily to London intending to murder her unfaithful lover. Amici miei (My Dear Friends, 1975), which mingles joy and despair in the director's trademark fashion in its tale of ageing friends who play juvenile jokes on one another to camouflage the realities of disillusionment, loneliness and failure, proved one of his greatest hits, breaking records in Italy and France. He said many of the cinematic jokes were based on his memories of a carefree childhood. The following year he won his final Oscar nomination, for Casanova '70, with Mastroianni as a roué who only enjoys seduction when it is fused with an element of danger.

Monicelli confessed that he took great fun in using players in a way that was different from their usual casting. "In Caro Michele (1976) I had Lou Castel, who had always played violent characters, and in westerns, act a rather weak and quiet homosexual. In my opinion, he's this character to a T. I was able to grasp another side of his personality, something that was the opposite of anything he had ever been asked to do. I did this again with Alberto Sordi in Un Borghese Piccolo Piccolo [A Very Little Man, 1977]. He is a comic actor and I had him play a very tragic role, very rough, even."

Sordi played a man who exacts revenge after his son is killed during a robbery, and Shelley Winters played his wife: "She used the Strasberg method and would not let me tell her what was going to happen next, as Strasberg said that in life people never know what is going to happen to them next." Caro Michele won Monicelli the Silver Bear at Berlin as best director, and he won the award again for Il Marchese del Grillo (1981) starring Sordi.

His last feature film was Le rose del deserto (Rose of the Desert, 2006), the story of a group of soldiers in Libya during the Second World War, which he directed at the age of 91. Two years ago his documentary Monti, about his adopted neighbourhood in Rome, was screened in Venice, Last year, still politically active, he called for students to protest against the government's proposals to cut the culture budget, and he was vocally critical of the state of the Italian film industry and in particular Italy's prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, whom he called a philistine and "a modern tyrant".

Diagnosed with terminal cancer, Monicelli committed suicide by throwing himself from a fifth-floor window of a hospital. Italy's President Giogio Napolitano said he would be "remembered by millions of Italians for the way he moved them, for how he made them laugh, and reflect."

Mario Monicelli, film director and screenwriter: born Viareggio, Tuscany, 16 May 1915; died Rome 29 November 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments