The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

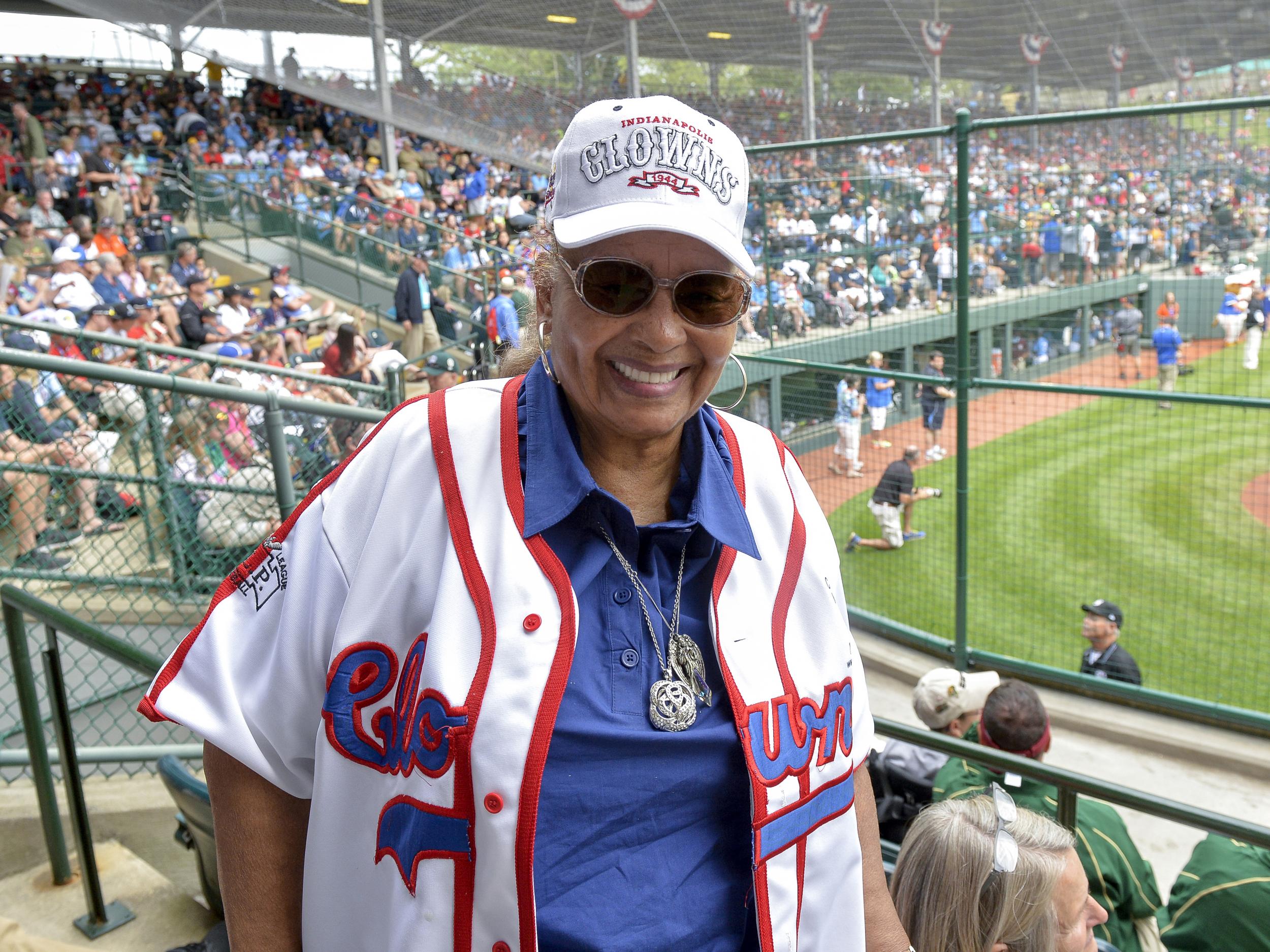

Mamie ‘Peanut’ Johnson: First female pitcher to play for the now defunct African-American baseball leagues

Refused by the all-white All-American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1953, aged 18 and undeterred, Mamie Johnson joined a clutch of women playing black men’s teams

In the 1950s, several years after Jackie Robinson became the first black player to take the field in a major-league baseball game in 20th century America, an African-American woman made baseball history of her own.

Mamie “Peanut” Johnson may have been slight, at 5ft 4in and less than nine stones, but she had a strong right arm and a competitive spirit that took her from the makeshift playing grounds of Washington into professional baseball, with the Indianapolis Clowns of America’s Negro Leagues – the very name a testament to an era when the injustice of segregation denied many lives and talents their full expression.

The leagues began operating around 1920 but have their roots in the late 19th century – because of segregation non-whites were barred from the sport until the late Forties, while the last of the black leagues disbanded in 1960.

Johnson, who has died aged 82, stood out in a world of hardened blokes, gruelling travel and low pay as one of three women to play in the Negro Leagues, and the only one who was a pitcher.

In 2013 her achievements were honoured at the White House where she met President Obama in a ceremony to recognise Negro Leagues baseball players.

Johnson’s brief professional baseball career ended before her 20th birthday, but in that time she accumulated a lifetime of colourful tales about a bygone era of baseball born of segregation.

“Those were some of the most enjoyable years of my life,” she said in 1998. “Striking out the fellows made me happy.”

She began playing the game in her native South Carolina, making baseballs out of rocks, twine and tape.

“I threw anything that had to be thrown,” she told The New York Post in 2001. “I was knocking birds off the fence with rocks, honey.”

As a child she had played alongside boys, preferring the faster, rougher game of baseball to softball, typically played by girls. While living in New Jersey, Johnson recalled, she was the only girl and only black person on her team. Later, after settling in Washington, she played on otherwise all-male church and semi-pro teams.

She was 17 when she and another young woman went to a tryout in Alexandria, Virginia, for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. Although major-league baseball was integrated by then, the women’s league was all white – as portrayed in the portrayed in the 1992 film A League of Their Own.

“They looked at us like we were crazy,” Johnson recalled in 1998. “They wouldn’t even let us try out, and that’s the same discrimination that some of the other black ballplayers had before Mr [Jackie] Robinson broke the barrier.”

A different opportunity arrived in 1953, after a scout saw Johnson dominate a line-up of men while playing for a team sponsored by a church in Washington. She was invited to try out for the Indianapolis Clowns, the Negro Leagues team that launched the career of baseball legend Hank Aaron.

As African American players began to fill big-league rosters, teams in the Negro Leagues struggled with attendance and quality of play. Before Johnson joined the Clowns, the team already had the first woman in professional baseball, infielder Toni Stone. A third woman, Connie Morgan, later joined them.

“Mamie could pitch, and Toni could hit,” ex-teammate Gordon Hopkins told The Washington Post in 1999. “It was no joke. It was no show. Somebody hit the ball down to Toni, Toni threw you out. Mamie, she was good.”

Johnson’s nickname came from an opposing player’s derisive comment that, when she stood on the mound, she looked no bigger than a peanut. Johnson struck him out, she recalled.

“I worked just as hard as the fellas,” she told The Post. “I pitched nine innings just like everybody else. Some fellas acted ugly, but when they found out I was a ballplayer instead of some gimmick, they accepted us.”

Records from the Negro Leagues are incomplete, and it is impossible to verify Johnson’s statistics with the Clowns. She claimed to have won 33 games and lost 8 from 1953 to 1955, when she returned to Washington to care for her young son.

Her earlier rejection by the women’s league, she said, was a blessing in disguise.

“If I would have played with the women,” she told the Kansas City Star in 2010, “I would have missed out on the opportunity that I received, and I would have just been another player.”

Born Mamie Lee Belton in Ridgeway, South Carolina, in the 1930s, she grew up with her grandparents after her mother moved to Washington to find work. She later lived with relatives in Long Branch, New Jersey, before settling in Washington in the late 1940s.

After her baseball career, Johnson studied nursing at North Carolina A&T State University and worked at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington for 30 years. She later operated a Negro leagues memorabilia shop in Capitol Heights, Maryland.

Her first marriage, to Charles Johnson, ended in divorce. Their son, Charles Johnson Jr., died in 2016. She was later married to Edwardo Goodman.

Survivors include her husband of 12 years, Emanuel Livingston of Washington; six stepchildren; several siblings; 19 grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren.

A baseball field at the Rosedale Recreation Centre in Washington DC was named in Ms. Johnson’s honour in 2013. A year earlier, she had met Mo’ne Davis, a Philadelphia child player who pitched her Little League team to the Little League World Series in 2014.

“She reminds me of me,” Johnson said. “I wasn’t no baby doll. No girlie girl. Baseball was all I knew. And I loved it.”

Mamie ‘Peanut’ Johnson, born 27 September, 1935, died 19 December 2017

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies