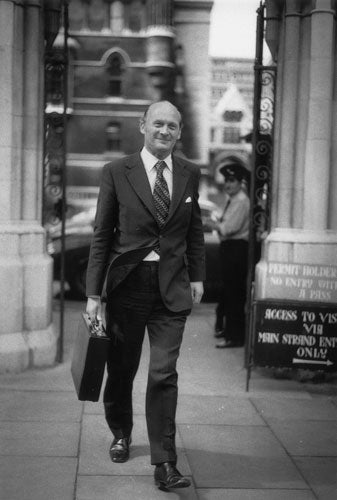

Lord Hunt of Tanworth: Cabinet Secretary who appeared in the High Court to contest publication of the Crossman diaries

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alas, people often lodge in the public mind and are remembered by posterity on account of comparatively minor and ephemeral episodes in the course of a long and distinguished life in public service. It is the fate of John Hunt, Secretary to the Cabinet, 1973-79, that he will forever be associated with his trundling to the High Court in 1974 and 1975, at the behest of Harold Wilson, to do his best to prevent or postpone the publication of Richard Crossman's The Diaries of a Cabinet Minister, at least for 30 years, on the grounds that they would reveal the inner workings of government. He failed. Lord Widgery, the Lord Chief Justice, found in favour of immediate publication.

Graham Greene, then managing director of Jonathan Cape, publishers of the diaries, which were also to be serialised in The Sunday Times, reflected to me that "a less obdurate man than John Hunt would have achieved some success against us. If he had not been so rigid we would have agreed to cuts in the diaries. But he was so difficult, so uncompromising, that we decided to publish without alteration. He missed his chance for a sensible settlement at the time that we submitted the diaries. He was very innocent, perhaps, about the determination of The Sunday Times to publish."

Hunt perhaps had been inflexible on this occasion, as he was on a number of other occasions. Yet on his retirement, when Greene asked him to lunch at the Garrick, he smiled gently and said: "How decent of you to bury the hatchet!" Years later Hunt told me that he himself was agog to read Crossman's diaries, not least what Crossman would say about the arguments and fraught discussions with the Treasury in 1965 when he was responsible for public expenditure and Crossman was tasked by Wilson to make quick, dramatic improvements in the housing situation before Labour, with a majority of five, and then three, had to go to the country for a second time.

I first met Hunt as a lowly PPS to Crossman, in the room when Crossman and his Permanent Secretary Dame Evelyn Sharp were struggling for more resources. He seemed aloof to me then, but after one meeting, knowing that I had been out to Borneo during confrontations with Indonesia and had had verbal fisticuffs with Lee Kuan Yew, took me aside. Though he was far too discreet to say so explicitly, I had the impression that he sympathised with my anxiety to save resources by withdrawing from east of Suez. Hunt who, at the end of the Second World War, as a naval officer, had accepted the surrender of a Japanese general, was sensitive to the aspirations of the peoples of east Asia.

Born in 1919, Hunt was the son of an Army major and was sent to Downside, the Roman Catholic school, where he was subject to severe discipline. With an exhibition in history to Magdalene College, Cambridge, he completed his degree in 1941. His supervisor was the distinguished medieval historian R.F. Bennett, who taught me 10 years later. Bennett was a scholar, insisting on total accuracy, and total accuracy, particularly in minutes of meetings, was one of the hallmarks of Hunt's success in the Civil Service.

Within a week of leaving Cambridge, Hunt was on convoy escort duty as a member of the RNVR, and was then posted in 1944 to the Far East. Joining the Civil Service in 1946, he opted for the Dominions Office and got his first break the following year with his appointment as Private Secretary to the up-and-coming Oxford don minister Patrick Gordon-Walker. Many years later, when I asked Hunt about Gordon-Walker, Hunt said that he had encouraged him to do what he had not thought of doing, "to go for positions in the pivotal centre of the government machine".

From 1948 to 1950 he was Second Secretary of the UK High Commission in Colombo and then in September 1951 became a senior civil servant at the Imperial Defence College. A successful spell as First Secretary of the UK High Commission in Ottawa brought him into contact with Sir Norman Brook, who was visiting Canada and who plucked him out in 1956 as his Private Secretary. This was the launch pad for the career in the stratosphere which Gordon-Walker had recommended a decade before.

In 1965 he returned to the Treasury, where he had been previously, as an Under-Secretary. Joel Barnett, at that time a prominent back-bench critic of his own government in relation to Treasury matters, but later Chief Secretary to the Treasury, told me that Hunt was outstandingly able at grasping financial matters. Years later, when both Hunt and Barnett were members of the upper house, Barnett succeeded Hunt as chairman of the sub-committee on European Trade and Industry. Perhaps, above all others, he was in the position to judge Hunt's clarity of mind.

In 1968 Hunt went as First Civil Service Commissioner, and was much involved in the implementation of the Fulton Committee report. Robert Sheldon, MP for Ashton-under-Lyne, had been appointed as a member of the Fulton Committee and reports how effective Hunt was in reducing the then 1,400 brands of Civil Service category to a manageable organisation.

It was on account of his sterling work in the Cabinet Office that Hunt came to the attention of Ted Heath, who made him responsible for negotiations under the general direction of Sir Con O'Neill for the intricate economic arrangements which would follow on joining the Common Market. His performance marked him out as the successor to Sir Burke Trend on his retirement as Secretary to the Cabinet in 1973.

In February 1974, perhaps unexpectedly, Hunt found himself serving a Labour government. Some have said that he became very close to Wilson, but this was not the anecdotal impression among my generation of MPs. The relations, since Harold Wilson always had a great respect for institutions and the Civil Service, were "correct" – but neither close nor cordial. Sir Robert Armstrong, now Lord Armstrong of Ilminster, who succeeded Hunt at Secretary of the Cabinet, vouchsafed to me that he believed this to be true.

Wilson in his book The Governance of Britain (1976) refers to a photograph of Hunt with the caption "a sentinel guarding the corridor linking the Cabinet Office and No 10 Downing Street". Wilson thought the comment was justified, as Hunt headed "the magnificent Rolls-Royce that is the Cabinet Office machinery". There may have been a bit of a froideur between Wilson and Hunt, as Hunt was conscious that Wilson thought that he had been Heath's especial choice ahead of more intellectual candidates. Hunt had no pretensions at being an intellectual, but was an efficient doer.

The late 1970s were a particularly difficult period. Hunt's exceptional capacity as a skilful chairman of various disaster and emergency committees helped the Government through many sticky situations. He always remembered that it was his job as Cabinet Secretary not just to serve the Prime Minister but to serve the cabinet as a whole.

One of the most delicate issues was that of Scottish devolution. Hunt was loyal to the position of the Prime Minister, James Callaghan, and what he told me years later were "the whims" of Lord Glenamara, then Ted Short, the minister responsible for the Scotland and Wales Bills. When he was in his eighties, he told me, I think truthfully, that he was for ever asking ministers "Do you really mean this? Do you realise what the unintended consequences could be for the unity of Britain?" and other pertinent, probing questions. He believed the establishment of an assembly in Edinburgh would lead to grief. He was a man who thought things through and chuckled "Your West Lothian question will never be answered because there is no answer to be had." And there never was.

Hunt had an immensely productive retirement. Not least of the good work he did in the evening of his life was to rescue the Roman Catholic weekly paper The Tablet where he was chairman from 1984 until 1996, as well as supporting the Catholic charity Cafod. He had married in 1973 Lady Charles, widowed sister of Cardinal Basil Hume, and I am told that he became a discreet counsellor to the Roman Catholic church. They never forgot the memory of his first wife, Magdalen Robinson, whom Hunt nursed through a period of illness at the same time as carrying out his crucial Civil Service responsibilities. He was helped by the fact that he was the most organised of men.

Tam Dalyell

John Joseph Benedict Hunt, civil servant: born Minehead, Somerset 23 October 1919; civil servant 1946-79, Assistant Secretary, HM Treasury 1962-65, Under-Secretary 1965-68, Deputy Secretary 1968-71, Third Secretary 1971-72; First Civil Service Commissioner 1968-71; Second Permanent Secretary, Cabinet Office 1972-73; Secretary of the Cabinet 1973-79; CB 1968, KCB 1973, GCB 1977; created 1980 Baron Hunt of Tanworth; married 1941 the Hon Magdalen Robinson (died 1971; two sons, one daughter), 1973 Madeleine Charles (née Hume, died 2007; one stepson, one stepdaughter); died 17 July 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments