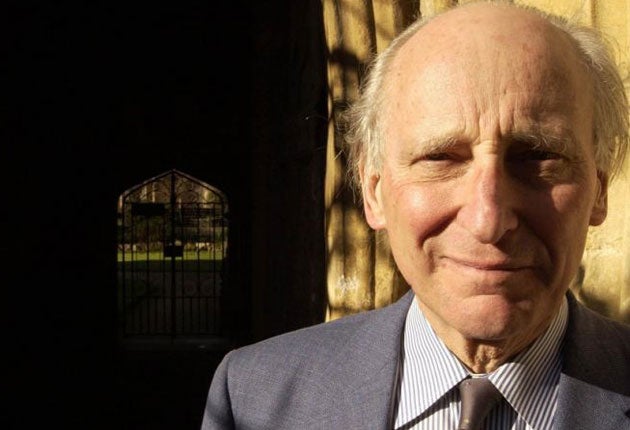

Lord Bingham of Cornhill: Lawyer who fought for judicial independence and was widely recognised as the greatest judge of his time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lord Bingham of Cornhill, the first holder of the top three legal posts in the country, was widely regarded as one of the UK's most distinguished legal minds and one of its most outstanding judges in the modern era. He served as Master of the Rolls, Lord Chief Justice and Senior Law Lord, and Sir Louis Blom-Cooper QC said of him, "It is no exaggeration to say Tom Bingham was the greatest judge of our time." Though he was seen as someone with insight, warmth and kindness, senior colleagues found him "frighteningly clever".

Despite his slightly old-fashioned demeanour, he had a modern and forwarding-thinking approach to justice. A staunch defender of judicial independence, which he saw as vital to the protection of human rights, Bingham was a huge presence on the legal landscape and his influence will be felt for years to come.

Born in London in 1933, Thomas Henry Bingham was the son of a Protestant Ulsterman. He grew up in Reigate, Surrey, where both parents worked as GPs. He won a scholarship to Sedbergh School in Cumbria, which was renowned for its Spartan regime; he went on to become head boy and was said to have been the school's brightest boy in 100 years. In 1954, following national service with the Royal Ulster Rifles, he read modern history at Balliol College, Oxford, where he won a Gibbs Scholarship and secured a First; an unsuccessful attempt in 2003 to become Chancellor of Oxford University was his only known setback. He was a keen speaker with a quick sense of humour and took part in the college debating societies.

Upon graduating, Bingham read for the Bar and in 1959 came top of the Bar finals, having won law prizes from both Oxford and Gray's Inn. He joined Leslie (later Lord) Scarman's chambers, where he established a thriving practice in general common law and commercial work; his clients included the Medical Defence Union and the Ministry of Labour (later the Department of Employment), where he spent four years as Standing Junior Counsel. During this period he gained a reputation for dexterity in cross-examination, clear mastery of points of law and for calmly and meticulously building up an argument in an innovative but resolute manner.

In 1972, he took silk aged only 38. The following year, he was made a recorder of the Supreme Court and in 1980 he became a high court judge in the Queen's Bench division and a judge of the commercial court, with promotion to the Court of Appeal in 1986. Bingham had never really felt comfortable as a trial judge and his new position gave him the freedom to exercise his sharp mind and to focus on legal principles rather than the finding of facts. Subsequently, even the best QCs found it an intellectual challenge when they appeared before Lord Justice Bingham.

It was while in this position that, in 1989, Bingham became the first judge to lend his support to the Lord Chancellor, Lord Mackay, who wished to reform the legal profession; his proposal was for a right of audience for barristers and solicitors in the high court. Many opposed this but Bingham believed the Lord Chancellor's proposals weakened none of the pillars on which the justice system rests.

"The great threat to the Bar lies not in the green paper, but in the Bar's reaction to it," he declared. "Let us not launch a hue and cry against phantoms that do not exist." However, Bingham did concede that judges still needed to maintain a degree of remoteness, stating that "It would be undesirable if we slipped over to El Vino's [the traditional haunt of Fleet Street lawyers and journalists] and were jugging it up with the boys."

Bingham came to wider public attention in 1977 when he was asked to chair an inquiry into allegations of breaches by oil companies of UN trade embargos against Rhodesia. In September 1978 his report caused a huge stir as it concluded that the companies had knowingly breached the sanctions with the complicity of British civil servants. Surprisingly, no prosecutions ensued.

Between 1991 and 1992 Bingham led the high-profile inquiry into the collapse of the Bank of Credit and Commercial International (BCCI), a Gulf Bank whose demise left creditors owed more than £9bn. His report, more scathing than anyone had predicted, criticised the Bank of England for its "deficient" supervision of the fraud-riddled BCCI and its regulation as "a tragedy of errors, misunderstandings and failures of communication". The Bank, he said, had ignored repeated warnings before BCCI's demise. The accountants, Price Waterhouse, meanwhile, could have communicated their suspicions to the Bank "more plainly and comprehensively."

Following the report, the bank's liquidators launched a case on behalf of thousands of BCCI creditors who were suing the Bank of England for its failure to properly oversee BCCI. The creditors sought £850m in damages, claiming that the Bank of England was guilty of misfeasance in public office. The case, however, collapsed in November 2005, with the Bank of England seeking to reclaim legal bills. The cost of the case to the creditors was reported to be as high as £100m.

In 1992, Bingham was promoted to Master of the Rolls, the second most senior judge in England and Wales after the Lord Chief Justice. During his four-year tenure he supporte the proposals by his eventual successor, Lord Woolf of Barnes, to overhaul the civil justice system, became the first senior member of the judiciary to advocate the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into English law and spoke out in favour of time limits on loquacious advocates, as well as supporting the use of plain English in the law and suggesting that judges should dispense with wearing wigs.

In 1996, Lord Mackay elevated Bingham to the position of Lord Chief Justice after the sudden retirement of Lord Taylor due to illness. Although he soon won over his doubters, his promotion surprised many because of his lack of criminal law experience. He also became a peer, Baron Bingham of Cornhill, of Boughrood in the County of Powys. This promotion from Master of the Rolls was unprecedented in the modern era, the last such instance occurring in 1900. Shortly after his promotion Bingham criticised Government plans to impose mandatory minimum sentences and end automatic remission for prisoners. He argued that judges were uniquely placed to decide which sentences fitted which crimes and pressed for the abolition of the mandatory life sentence for murder. He later attacked the media for portraying judges as excessively lenient. In addition, he welcomed the growing trend towards judicial review and backed the international criminal court in the face of American criticism, as well as recommending a review of drugs law, in particular the relaxation of cannabis laws, and expressing his reservations over plans to dismantle the legal aid scheme. He oversaw a series of ground-breaking judgements in various fields of law.

From 2000 until his retirement in 2008, Bingham was a senior Law Lord. His appointment came in the aftermath of the Pinochet débâcle, and again sparked controversy as the post was usually given to the longest-serving member of the House of Lords judicial committee. A factor in his selection was thought to be the advent of the Human Rights Act, which placed the Law Lords in a new, more high-profile role in deciding socially sensitive issues.

Bingham favoured incorporating the European Convention on Human Rights into domestic law (the Human Rights Act 1998) and also divorcing the judicial branch of the House of Lords from Parliament, to create a separate supreme court. The Supreme Court began to function in October 2009, after his retirement, and while he slightly regretted not becoming its first president, he was delighted by its arrival. Following his retirement in 2008, Bingham showed no signs of ducking issues and argued that Britain's invasion of Iraq was a "serious violation of international law".

His lectures and writings, particularly his last book, The Rule of Law, (2010) are treated as seminal texts. Over the years he received many awards. In 2005, he was made a Knight of the Garter – the first judge to be granted the honour. He died of lung cancer at his home in Wales, surrounded by family. He is survived by his wife Elizabeth and their three children and six grandchildren.

Shami Chakrabarti, the director of Liberty, summed up what many felt: "As long as people anywhere fight torture and slavery, treasure free speech, fair trials, personal privacy and liberty itself, Lord Bingham will be remembered."

Thomas Henry Bingham, jurist and judge; born London, 13 October 1933; QC 1972; a Recorder of the Crown Court, 1975–80; Judge of the High Court of Justice, Queen's Bench Division, and Judge of the Commercial Court, 1980–86; a Lord Justice of Appeal, 1986–92; Master of the Rolls 1992–96; Lord Chief Justice 1996–2000. Kt 1980; cr. 1996 Baron Bingham of Cornhill; KG 2005; married 1963 Elizabeth Loxley (one daughter, two sons); died 11 September 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments