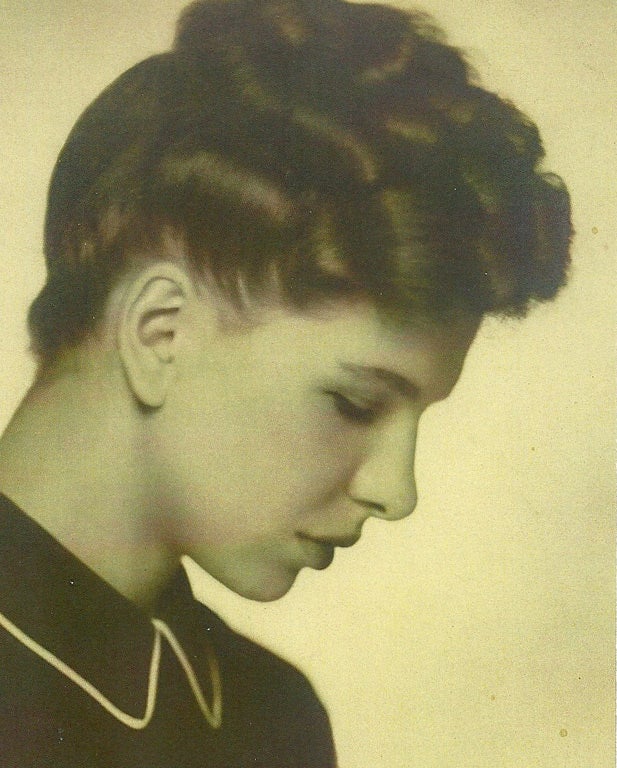

Leila Berg: Author and editor who revolutionised our approach to children's literature

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Intensely combative from her earliest years, Leila Berg, who has died aged 94, galvanised attitudes towards young readers in the UK.

Her once controversial views about the importance of making a good fitbetween all children and their first books have now become part of normal publishing practices. Her libertarian educational beliefs, in common with the ideas of her friends AS Neill and John Holt, have fared less well in today's more unforgiving classroom climate.

Born Leila Goller, she was brought up in a Jewish community in Salford where there was only one Christian house in the street. Her father, a doctor, adored Leila's older brother, but had no time for girls; Berg later claimed he never addressed a word to her until she reached adolescence. The marriage was not successful, finally ending in separation. Berg attributed her lifelong passion for insisting on the rights of children to be loved and cherished back to those early unhappy years. Her impressionistic autobiography Flickerbook (1997), describing that time in her life, was chosen by Waterstones as its Book of the Month.

A precociously early reader and writer, she won a scholarship to Manchester High School, where she did well. But with her contrarian spirit already in full flower, she refused the chance of university in favour of fully committing herself to working for the Young Communist League. Two early lovers she met at this time died in the Spanish Civil War. In 1937 she soon abandoned a course in teacher training but unwillingly completed a diploma course in journalism later on at London University. By now living with her father, following a cautious reconciliation, she was a journalist for the Daily Worker before getting married to Harry Berg in 1940. Bombed out of their house while she was heavily pregnant, she and her husband moved to the country. A son and then a daughter followed, with the marriage ending in 1974.

Berg published her first children's picture book in 1948, drawing on experience with her children and also on having opened her own nursery. Lively and energetic, her Little Pete Stories (1952) were particularly popular, among a stream of other titles she produced. Appointed children's books editor at Methuen in 1958, she moved to Thomas Nelson before finishing at Macmillan Educational, the base from which she went on to make her major impact with the Nipper series in 1968. Reacting against the passionless suburban world of the Ladybird books and Janet and John, this radical new series began as 14 supplementary readers for small children deliberately targeted at what she called "ordinary homes".

Berg had already spent time in school playgrounds, talking and listening to children and noting the more acceptable words that they often came up with in their games such as "hospital", "ambulance" and "accident". So why not go for stories that included everyday words like these along with the jobs, streets, homes, idioms and faces familiar to working-class children but normally invisible in early-reading books?

Some titles she commissioned, including one from the novelist JL Carr, but many more she wrote herself. Illustrators were implored not to make everything seem ultra-clean and tidy, with dustbins looking as if they had come straight from Habitat. Instead, stories were to take place in flats and terraced houses where the roofs sometimes leak and Mum occasionally loses her temper. "What shall we wear for the seaside?" asks Dad in A Day Out. "Just knickers," answers Debra, holding up her skirt. Later, the family travel to the coast by van, Dad enjoying a bottle of beer on arrival. With a free copy sent to every school, the series and its successors proved popular, with the sprightly stories and illustrations winning over young readers from all backgrounds.

In 1968 Berg published the outspoken polemic Risinghill: Death of a Comprehensive School. This searing account of a north London state school closed because it was thought to be too liberal was later turned by her into a play. Berg was never in doubt that the headmaster, Michael Duane, by now a friend, had been needlessly sacrificed for encouraging pupils to challenge authority. Others argued that the picture was more complex, but no one remained untouched by the passionate writing that made this book an instant best-seller over the next few months.

More books followed. Look at Kids (1972) is a collection of affectionatevignettes about childhood accompanied by numbers of photographs, while Reading and Loving (1977) advises parents and teachers on how best to share books with small children. The God Stories (1999) consisted of re-worked tales from the Old Testament shorn of their religious content.

Moving out of south London in 1974 to Wivenhoe in north Essex, where she took an active part in village life, Berg found some of the tranquility she had always been searching for. She won the Eleanor Farjeon Award for services to children's literature in 1973, and was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Essex in 1999. As she said at the time, "All my life I have sought to empower children".

Battling against arthritis, she opted for voice-recognition software when she could no longer use her hands. She kept in touch with her many friends, both young and old, as well as with her four grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Finally moving to a residential home in 2011, she died in Bury St Edmunds Hospital after a fall. Her death robs young people of one of their most intractable champions.

Leila Goller, author and political activist: born Salford 12 November 1917; married 1940 Harry Berg (marriage dissolved 1974; one son, one daughter); died Bury St Edmunds 17 April 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments