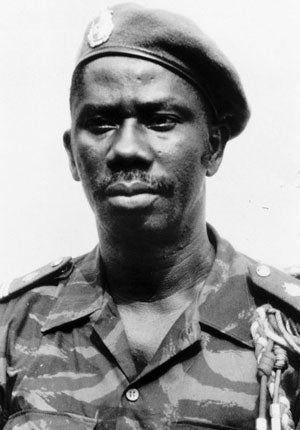

Lansana Conté: President of Guinea who ruled the West African nation for 24 years after seizing power in a military coup

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The death of the West African dictator Lansana Conté – and the suffering he inflicted on Guinea during his quarter century in power – can't help but bring to mind President Robert Mugabe's southern African sit-in. Conté's death comforts the depressing view that only nature can remove a president who decides that he is the incarnation of his nation, no matter the potential wealth of the country or the extent of organised, internal opposition.

For at least his last five years, the reclusive Conté's declining health – he suffered from diabetes and possibly leukemia – led to persistent rumours of his passing and false hopes that he would relinquish power. Only a week before he died, a newspaper editor was arrested for publishing a cartoon showing the president struggling to stand up, and was ordered to print a photograph of Conté in good health.

Guinea was France's richest outpost and Conté, a farmer's son (born in 1934, although he never revealed his exact date of birth), received colonial military training between 1953 and 1956 at the Charles Ntchoréré Military School at Saint-Louis in what is now Senegal. He was posted to Algeria during the war of independence there. On Guinea's own independence in 1958, he rose rapidly through the ranks of the new state's army as a loyal supporter of President Ahmed Sékou Touré. By 1975, he was chief-of-staff.

The ruthless, pro-Soviet Sékou Touré had been in power for 26 years when he died in March 1984. A month later, Conté seized power and abolished the constitution. Sensing that military dictatorship was going out of style, Conté in 1990 installed the best constitution in West Africa, limiting presidential terms, allowing multi-party elections and creating a framework for the devolution of power.

He was elected president in 1993. He was re-elected in 1998, but only after locking up the opposition candidate, Alpha Condé. From then on, his reign became characterised by constitutional tinkering to keep himself in power, favouritism for his Soussou tribe, discrimination against Alpha Condé's Mandinka tribe, and an obsessive fear of overthrow. The European Union considered Guinean elections so corrupt that it didn't bother to send official monitors.

Sékou Koureissy Condé served as security minister from 1997 to 2000 – the years during which Conté dropped any pretence of being a reformer. The former minister, now living in the United States, told Guinéenews, an expats' newsletter, that Conté appeared to change tack after 1998, as a result of realising how popular Alpha Condé was. Koureissy Condé said: "There was more and more going wrong. Three weeks before I resigned in 2000, he listened to me at length. I listed my worries over the state of the civil service, the state apparatus, corruption, the working conditions of the police, the porous state of our borders and the general sense of abandonment and negligence I felt in the country.

"He appointed prime minister Lamine Sidimé in March 1999 to handle two things – the presidential election and the issue of Alpha Condé. It seems to me that there were two groups in the government – those in favour of Conté's referendum (to change the constitution and remain in power), like Sidimé, and the rest. The president decided to follow Sidimé's guidance and from then on he lost all his friends, all his allies."

But regional instability worked in the Guinean president's favour. Conté's hatred of the Liberian warlord-turned-president Charles Taylor – viewed by the outside world as the principal source of rebel warfare in West Africa – earned him the tacit support of the United States. Britain, which had entered a war against Taylor's Revolutionary United Front in Sierra Leone, showed him complaisance.

The 10 million population paid the price, living in extreme poverty, in a culture of great fear, on a patch of the planet which geologists say contains more minerals – such as lucrative bauxite – than any other. The people of Guinea only rarely heard from their president whose public appearances increasingly served merely to quash rumours of his death. Of late, Conté had no image to nurse. He didn't even know the basic rule of African popularity politics – to exploit football: before international matches in 1997 and in 2002 his pep-talk to the players consisted of an order banning dreadlocks from the national team.

In an election boycotted by all prominent opposition figures, Conté was elected for a third term in 2003. By then, he was frequently travelling to Morocco for medical treatment and many thought he would not last another term. In January 2005, he survived an attack on his motorcade in which two of his bodyguards were shot. Conté said that God had saved him.

Inflation began to bite. With it, the labour force became restive and the army divided. Food riots in 2006 were violently suppressed by police using live bullets. In January 2007, anti-government forces organised a general strike. At a meeting with trade union leaders, Conté declared: "As many as you are, I will kill you. I am a military man. I have already killed people".

The strike was called off after three weeks when, after a West African mediation effort, Conté promised to share power with a prime minister. But the man Conté appointed, Eugene Camara, was seen by the opposition as too close to him and the strike resumed. Conté declared martial law but it crumbled amid protests from soldiers who were not being paid. The endgame was left to Conté's declining health and Guineans knew that their president's time was up when he failed to appear on television last month to mark the Tabaski Muslim holiday.

But it remains to be seen whether Conté's death will bring democracy and development to Guinea. Hours after Prime Minister Ahmed Tidiane Souaré announced the president's death, a group of soldiers declared that they had taken power. Only time will tell whether Guinea is about to experience a cruel rerun of Conté's ascent to power 24 years ago.

Like Mugabe, who came to power with British support in 1980, Conté essentially survived for as long as he did thanks to western sponsorship. By the time the outside world lost interest in him as an ally, he was too firmly settled to budge.

Alex Duval Smith

Lansana Conté, politician: born Loumbaya-Moussaya, Guinea 1934; President of Guinea 1984-2008; married; died Conakry, Guinea 22 December 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments