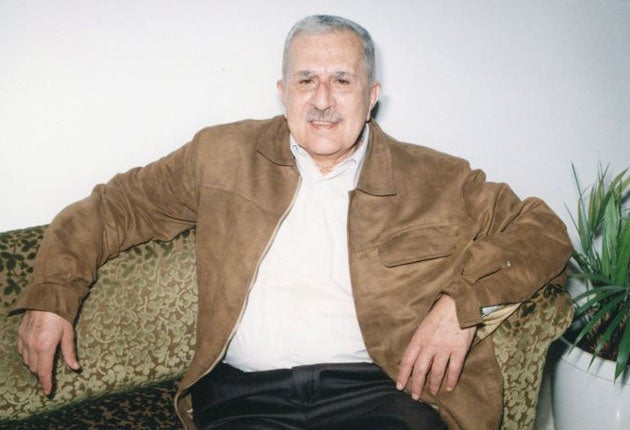

Kamal Salibi: Scholar and teacher regarded as one of the foremost historians of the Middle East

Almost two decades ago, recording a BBC radio programme on Islam, I dropped by the American University of Beirut to interview an old Christian Protestant friend, Kamal Salibi. I asked him the same question I had already put to many Muslims: what happens after death? They, of course, assured me of their belief in an afterlife. Salibi, the great breaker of historical myth, did not share this conviction. "After life is nothing," he said, eyes cast slightly upwards, his voice almost shaking with indignation. "It is the end. We are dust."

I sincerely hope not. For Salibi, who died last Thursday after a stroke, was perhaps the finest historian of the modern – and the old – Middle East, fluent in ancient Hebrew as well as his native Arabic, his English flawless, a man whose work must surely shine into the future as it has illuminated the past. In one sense, his desire to deconstruct history, his almost Eliot-like precision in dissecting the false story of the Maronites of Lebanon, his highly mischievous – and linguistically brilliant – suggestion that the tales of the Old Testament took place in what is now Saudi Arabia, rather than Palestine, made him a revolutionary.

In one sense, his wish to live in a world unstifled by the texts of dictators made him one of the founders of the new "Arab awakening", 30 years before his time and scarcely 40 years after George Antonius first used the phrase as the title of his great work on the British betrayal of the Arab revolt. History, Salibi believed, should not only draw on original sources but should have a beginning and a middle. He was a "chronology" historian – such creatures are now back in fashion, thank God – who was also the first Lebanese writer to confront the country's civil war. His Crossroads to Civil War, Lebanon 1958-1976 was published less than 12 months after the 15-year conflict began.

Kamal Salibi never showed his age – he was born in 1929 in the Christian hill-town of Bhamdoun – perhaps because he so enjoyed the company of younger people, both his students at the American University and his later companions in the Jordanian Prince Hassan's Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies in Amman. He was a gentle, simple man whose respect for the views of others was balanced by his scorn for the world's hypocrisy. He often blamed the arrogance of Christians for their own fate in the region. How he would have loathed Lebanese Maronite Patriarch Beshara Rai's recent half-support for the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Paris, an echo of the widespread Christian suspicion that only strong dictators can protect Christian minorities from Islamist extremism. Salibi, like his contemporary, the late historian Yusuf Ibish, admired the Ottoman Empire and was contemptuous of the West's destruction of the Caliphate.

"You often forget that one of the reasons you fought the First World War was to destroy the Ottoman Empire – but the Ottomans, in their last years, they wanted to be like the West," he told me one afternoon in his English department tutorial room, always the teacher, always mixing emotion with the kind of detail that obsessed him. "The Sultans and his closest advisers learned to paint. They learned to play the piano. The Ottomans wanted to be like you. So you destroyed them."

He was a brave man. When thesectarian civil war began to target the Christians still living in West Beirut, he chose to stay on in his beautifulOttoman home in the Hamra district, scarcely a hundred metres from the 1920s villa in which Ibish lived. When the Lebanese army broke apart and Christian units bombarded thedistrict, Salibi fled to a neighbour as shells destroyed his home. Ibish stayed downstairs in his own house, reading Hamlet as the upper floors burned. But when a local paper drew attention to the meaning of Salibi's name – in Arabic it means "crusaders" – he set off for Jordan to help establish Hassan's foundation.

He quickly became a confidante and adviser and was able to give me the prince's account of the final break with King Hussein when the latter decided that his brother Hassan should no longer be heir apparent. The prince had laid his pistol on the king's desk and invited his brother to shoot him if he believed he was plotting his overthrow or preparing for his demise. The king – who was to die of cancer a few weeks later after making his son Abdullah Crown Prince – handed Hassan an official letter renouncing his role as the next king; Hassan heard the contents read on the news over his car radio before having the chance to open the envelope.

Several years later, after Hassan had unwisely mapped out the future of Jordan in the Middle East at a conference in London, King Abdullah was understandably enraged. Hassan sought Salibi's advice. "I told him to go and see the king at once," Salibi recalled for me. "And I told him to tell the king that he was very, very sorry." Good advice from a wise man who never tried to enrage anyone. Indeed, he was the only visitor to come to my home and be warmly greeted by the family cat – a "scaredy-puss" if ever there was one, always fleeing from visitors – who would leap upon Salibi like a long-lost friend.

But Salibi made enemies aplenty when he published The Bible Came from Arabia, a long and detailed linguistic exegesis in which he claimed to have discovered – through long research into place names – that the lands of the Bible and of historical Israel were not in Palestine at all, but in Arabia; in fact, in that part of the peninsula which is now Saudi Arabia. Salibi was intensely proud of his achievement, refusing to be cowed by the storm of often abusive criticism which he provoked. Israel's self-appointed defenders in the West condemned Salibi for trying to delegitimise the Israeli state – it is surprising how long the fear of "delegitimisation" prevailed in Israel, as it still does today – while more prosaic writers treated the author with good-humoured contempt. A reviewer in the Jewish Chronicle referred to Professor Salibi as "Professor Sillybilly", a wonderful crack that I forbore to repeat to Salibi himself.

The Saudis, true to their fears that the Israelis might decide to take Salibi seriously and colonise the mountains of Sarawat (which Salibi believed was the real "Jordan valley" of the Bible), sent hundreds of bulldozers to dozens of Saudi villages which contained buildings or structures from Biblical antiquity. All these ancient abodes were crushed to rubble, Taliban-style, in order to safeguard the land of Muslim Arabia and the house of Saud. At the time of the Prophet there had indeed been Jewish communities in Arabia. Salibi – wisely or not – never abandoned his Arabian convictions. The last time I saw him, he was offering me a new edition of his Bible, with a laudatory new preface by an American academic, in return for a hitherto undiscovered Dumas novel about the Battle of Trafalgar.

The Druze leader, Walid Jumblatt, caught the nature of Salibi's work accurately when he wrote this week that Salibi sought through scientific-historical research "to overcome inherited beliefs which had taken on a sacred character". He was talking about the book which will still be read in a hundred years, A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered in which he emphasised the place of Christian Maronites in the Middle East, insisting that they did not come to Lebanon as a persecuted minority – one of the stories which Lebanese often repeat to account for the cluster of Maronite towns in the high mountains around Bcharre. The predicament of the Christians of Lebanon had always fascinated him – his PhD at SOAS, under the supervision of Bernard Lewis, was entitled "Maronite Historians and Lebanon's Medieval History" – and was also the subject of his greatest despair.

"I like to give my students," he told a reporter four years ago, "a passage from an historical document and ask them: 'What does it say?' Also, 'What does it not say?'...Correct reading, it used to work wonders." It still does. Which is why, for Salibi, the end can not be dust.

Kamal Sulieman Salibi, historian and teacher: born Bhamdoun, Lebanon 2 May 1929; died Beirut 1 September 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments