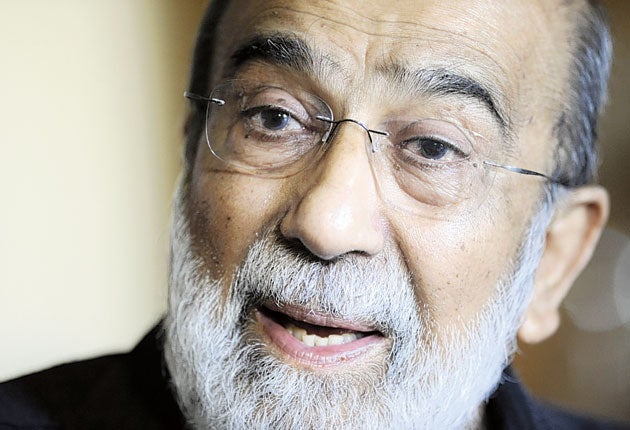

Kader Asmal: Human rights and anti-apartheid activist who became a minister in South Africa

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Kader Asmal became Minister of Water Affairs in the liberated South Africa he gave urgent priority to one small but rewarding project; connecting clean drinking water to the home of the widow of Chief Albert Luthuli, Nobel Peace laureate and one-time president of the African National Congress. He saw Luthuli, a non-violent Methodist minister, as his mentor. Asmal was noted for his robust criticism of the ANC government's drift away from the protection of human rights. Archbishop Desmond Tutu said he had "served his people and his nation without a thought of self-enrichment or aggrandisement. Short of stature, big of heart and mind, he enriched us all."

Abdul Kader Asmal grew up in Stanger in Kwa-Zulu Natal, one of10 children of a shopkeeper fatherwho had emigrated from Gujarat in India. As a 14-year-old he met Luthuli, who lived in the nearby African village of Groutville. Asmal said later that Luthuli "enabled me to see the possibilities we could achieve in a country free of racialism."

On leaving school he qualified as a teacher then obtained a BA degree by correspondence. But his real aim,having seen reports of concentration camp victims at his local "bioscope', was to be a lawyer. In 1959 he cashed in his teacher's pension and boughta ticket to England. His arrival coincided with the first boycott of South African goods, and in the same year he was one of the founders of theAnti-Apartheid Movement, which would grow into a worldwide pressure group. All his student days, he recalled, "apart from one month studying for my finals, were devoted to the AAM, five or six hours every day." It was enough to make him persona non grata in the land of his birth.

After graduating at the London School of Economics he began a lengthy stint at Trinity College, Dublin, lecturing in human rights and international and labour law. He was known for a voluble, teasing, always encouraging teaching style. He practised human rights in public life as well, founding the Irish version of the AAM, chairing it for many years, and the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, which he presided over for 15 years. He was vice-president, under Canon John Collins, of the International Defence & Aid Fund for Southern Africa (1968-82). He lent his weight to civil rights campaigns in Northern Ireland and Palestine and participated in several international inquiries into human rights violations. In 1983 he was awarded the Prix Unesco for the advancement of human rights.

At last, with Mandela's release from prison, Asmal, with his English wife Louise, could return home. TheUniversity of the Western Capeoutside Cape Town hired him asprofessor of human rights but there was more urgent work to be done. The exiles had been out of circulation for as long as, often longer than, the leaders imprisoned on Robben Island, and they too longed to get to grips with the democratic South Africa project.

Election to the ANC's National Executive Council guaranteed him aninfluential role in the negotiations. He had joined the ANC constitutionalcommittee in exile at its inception in 1986; now, in talks within the liberation movement, then, in tough bargaining with the Afrikaner nationalists, he was more insistent than most on the inclusion of a bill of rights in a new deal for the riven multicultural nation. It has since become a cornerstone of the country's judiciary.

When Mandela appointed him Minister of Water Affairs he joked that "the only thing I know about water is the ice I put in my John Jameson's." But he set about with a will to connect clean water to millions who did not enjoy this basic human right. Bringing water to Mrs Luthuli gave him especial pride, but then to his disbelief he discovered that ancestral home of the President of the Republic in Qunu, Transkei, was not connected. He was careful to tap into private funding to remedy the situation. He drove himself tirelessly and would stand in for ministerial colleagues at all sorts of occasions, speaking with facility whatever the subject.

In 1999, the new president, Thabo Mbeki, switched him to Education, where the remedies required to repair the ingrained injustices of apartheid were much more profound. He had been diagnosed with bone marrow cancer but this hardly seemed to inhibit the energy, the constant debating, the cajoling about the best and quickest way to reduce illiteracy and give more black pupils the chance in life that had so long been beyond their reach. The former "white" universities were told to enrol more black students and hire more black lecturers or face having quotas imposed on them. With the 2004 elections, he was, to his disappointment, replaced at Education.

Out of office but still a senior party member party and an MP, he began to speak out about what he saw as worrying trends in the ANC. At the launch of Judith Todd's book on her native Zimbabwe in 2007, he delivered a powerful condemnation of Robert Mugabe, in contrast to the government line of persuasion by "quiet diplomacy". A year later he resigned from Parliament in protest at the disbanding of the Scorpion police unit that investigated corruption in high places. In the wake of its disappearance, graft and showy materialism have increased alarmingly.

A week before his death, in what turned out to be his final public pronouncement, the lifelong defender of human rights urged his own party to drop the Protection of Information Bill. The measure will jail journalists for disclosing "unauthorised information", while excluding protection for whistle-blowers or a public-interest defence. "My conscience will not let my silence be misunderstood," he said. "I ask all South Africans to join me in rejecting this measure in its entirety."

Kader and Louise lived modestly in Cape Town's southern suburbs, where he might be seen walking on Rondebosch Common with his grandson Oisin. He was a patron of Friends of Rondebosch Common.

Abdul Kader Asmal, lawyer, human rights activist and politician; born Stanger, Natal 8 October 1933; married Louise Parkinson (two sons); died Cape Town 22 June 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments