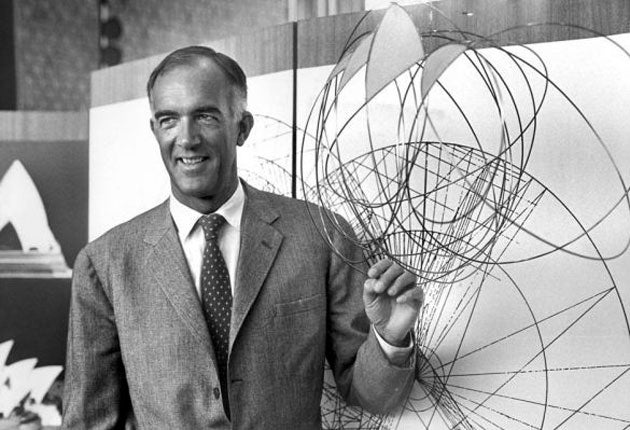

Jorn Utzon: Award-winning architect who designed the Sydney Opera House

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the time of the Australian Bicentennial celebrations in 1988, Sydney Opera House was voted one of "the wonders of the 20th century". However, during the building's problematic construction period, from 1961 to 1973, it was nothing of the sort.

Jørn Utzon, its Danish architect, won the international competition for the project in 1957 and signed thecontract for the first stage of the scheme in 1961. Aware that there were fundamental problems with theconstruction of the parabolic concrete shells of his roof design and finding that budgetary and detailing issues were getting out of hand, he left the site in 1966. The complex was completed by others and the building opened officially in 1973. Utzon did not attend. The key original element was a large opera hall but this was reduced in a change to the brief from a major to a minor auditorium. Altogether thefollowing stages were an unholy compromise and Utzon was never persuaded to return to see the outcome of his work.

A few years later the political climate changed and the building's distinctive profile was to put Sydney on the "World Cities" list, as well as the cultural tourist map and Australian postage stamps. Its dramatic position, on a shelf surrounded by water on three sides, gave it the appearance, some thought, of a great mother ship around which all other vessels revolved: a locus in one of the most breathtakingly beautiful harbours anywhere. The question of scale – of an appropriate scale – was also beautifully achieved in the natural harbour. Here Utzon excelled. The object creates the place. The building was to be framed, but not overwhelmed, in one direction by the great hanger bridge and in another by fast-growing trees and a civic renovation and development scheme that has done much to enhance the opera house's site.

Sydneyites eventually came to terms with their own world-famous building, which overtook the somewhat overrated Bondi Beach and Sydney Harbour Bridge itself as an object of tourist desire. As an Australian colleague said over the weekend: "I really can not think of Sydney without it". Despite the many vicissitudes that the structure and the plan underwent, the Opera House remains a powerful and comprehensive complex, indelibly tied to its dramatic site, a voluptuous, exciting, unique cultural flume sitting astride a bedrock of granite on Bennelong Point.

The original concept drawings submitted for the competition were simple and diagrammatic, yet profound – a portent of a new kind of modernist architecture. The American Eero Saarinen and Britain's Leslie Martin were the two foreign architect assessors, and they saw something special in Utzon's design. Later Saarinen referred to it as a scheme that showed a "beautiful movement of people within that architecture". All the assessors admired the "Classical" treatment of the Bennelong Point site which was to accommodate the massive base and to be resurfaced by what the judges saw as a "magnificent ceremonial app-roach to buildings that provided a unity for structural expression".

Utzon himself later explained his ideas: "I had to visualise five to six thousand people going out to that peninsula, which is perhaps 600 by 300 feet, so automatically I made this peninsula into a 'rock' and put everything to do with preparation (rehearsal rooms, workshops, etc) underneath the big 45ft high platform ... finished plays were presented to the audience on top of this 'rock' covered by the big sails... People were separated from daily life by this fantastic building."

The forms of the original Opera House design were immensely daring and some saw them as unbuildable, which was partially true. However, it was not an entirely novel design but a product of the current architectural Zeitgeist – a Modernist building of the romantically expressionist, organic sort, part of the same ethos that produced Le Corbusier's wonderful Ronchamp Chapel, in eastern France – which, more than any other single building of the period 1950-55, revolutionised and changed the course of contemporary architecture – and Eero Saarinen's expressive Yale Hockey stadium of 1956 as well as the riotously curved carapace of the TWA Terminal at New York's main airport.

The Sydney Opera House proved to be a test bed for many of Utzon's later architectural ideas and represented a moment of sheer design virtuosity but it was also a profoundly distressing and unhappy experience, although he remained unfazed as an architect.

Born in Copenhagen in 1918, the son of Aage Utzon , a naval architect who had trained in Britain, Jørn Utzon studied at the Royal Academy School, Copenhagen from 1937, taking an extensive world study tour after graduating. He left Nazi-occupied Denmark in 1942 for Sweden, returning home after the war. By the time he won the Sydney job, at the age of 38, he had produced a couple of exquisite estates of linked patio houses, the first in the port of Elsinore, some eight kilometres from his house and studio in Hellebaek, a village on the north coast of what he good-humouredly referred to as "Little Denmark".

The English architect James Thomas recalled his impressions of Utzon, when he worked in his office in 1960, as "a charming, handsome man who cared about his appearance, someone who was relaxed about his positioning in the architectural world". His smart suits came from Savile Row while his practical and mischievous sense of humour was typically Danish. Utzon's freehand drawings were superb and often produced in discussions with his staff.

Utzon's architecture was about light, sunlight and its penetrating, reflective qualities, as well as massive ground bases and dominating roofs that derived from his interest in the Mayan idea (Monte Albán, Mexico)of the earth as a ground platform and the openness above dominated bysky and clouds. Writing in the Italian architectural journal Zodiac 14 in 1965 he emphasised this mythological but functional analogy: "On top of theplatform the spectators receive the completed work of art and beneaththe platform every preparation for it takes place".

This was a simple idea, but in the translation to the design for the Opera House, it required a geometric solution for the intricate roofscape. The segments of a sphere eventually proved to be the answer, replacing the original idea of the parabolic-shaped shells. Aided by the team of the engineer Ove Arup, with the pioneering use of computers, the technological advance that this gave provided a solution for the geometry of the roofs and the subsequent details for the roof beam lengths and the tiling.

There were other precedents that inform the basis of Utzon's views. He had gained an insight into the work of articulate, regional and site-conscious designers such as Alvar Aalto, for whom he worked for a short period in Finland in 1945. Study tours with his friend the architect and writer Tobias Faber took him to see the work of Frank Lloyd Wright in the United States. Chinese influences abounded in his work as did the wood construction of the Japanese carpenter, and he was much inspired by the 1917 book On Growth and Form by D'Arcy Thompson, an almost biblical text for architects of the "organic" persuasion.

Utzon had worked with his friend Arne Korsmo in Stockholm, later a pioneer of post-war modernism in Norway, while his great Swedish hero was E. Gunnar Asplund, who changed the way architecture looked in Sweden through the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930. Utzon visited the fair with his parents; after seeing Asplund's pavilion they all experienced a transformation of their ideas and ideals to a more frugal, functional lifestyle.

Echoes of many of these inspirational incentives for Utzon's own ideas are to be found in buildings of great subtlety and originality that followed the Opera House, including the huge Kuwait National Assembly building (1972-82), which suffered untold damage during the First Gulf War but which brought out the idea of the narrow bazaar street and the patio courtyard plan entered through a huge, concrete tented form of lobby.

His first commission in Denmark after the Sydney débâcle was for the Lutheran church at Bagsvaerd (1976). Its industrial-looking exterior belies its sublime interior space, which was described by the church minister as a place where people are "gathered under clouds through which a heavenly light passes forth". Unlike the dark, unlit Scandinavian churches of Lewerentz (which Utzon admired) he bathed the church and sacristy in a light with an undulating curved wave-like ceiling. Other internal spaces, in contrast, were as plain as a Japanese garden.

In the early 1970s Utzon acquired some land in Majorca and built his first "retirement" villa by the sea. "Can Lis" (named after his wife) was followed by another beautifully conceived house away from the coast. Recently he had returned from the Spanish island to settle back in Copenhagen.

Although he never went back to Australia, in 1999 Utzon was invited to work again on the Sydney Opera House. In collaboration with his son Jan and the Sydney architect Richard Johnson, he developed a set of design principles for future changes to the building and worked on the interior, refurbishing the Reception Hall and designing a wall-length tapestry to hang in the foyer.

Utzon received many honours, including the Order of Australia and the Gold Medal Awards from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (1973) and the Royal Institute of British Architects (1978). In 2007 Sydney Opera House was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Dennis Sharp

Jørn Utzon, architect: born Copenhagen 9 April 1918; married 1942 Lis Fenger (two sons, one daughter); died Copenhagen 29 November 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments