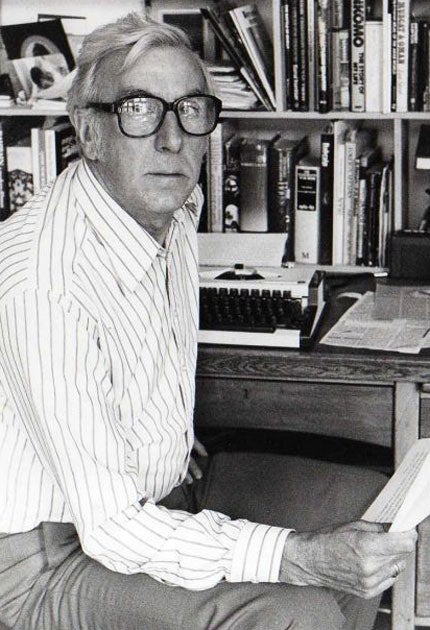

John Bulloch: Highly respected journalist and Middle East expert who was also Diplomatic Editor for 'The Independent'

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

John Bulloch was one of the most highly-respected foreign and diplomatic correspondents, Middle East experts and authors of his era – from the early 1960s into the new millennium – the author of more than a dozen books, notably on Iraq, Lebanon, the Gulf and Kurdistan. He was also a driving force behind the launch of The Independent in 1986 and The Independent on Sunday four years later. He was one of the last dinosaurs of Fleet Street, where many a younger journalist would sneak closer to him in the King and Keys pub to eavesdrop on his stories from faraway places – the Congo, Oman, Persia.

Bulloch made his mark as a foreign correspondent and diplomatic editor at The Daily Telegraph for a quarter of a century before joining the fledgling Independent as Middle East editor. In this newspaper, and its Sunday sister, his byline provided the kind of clout that made both papers successful against tough odds and doomsayers. He was a "journalist's journalist," fierce in his dedication to getting the story out, but a gentle giant to younger correspondents, even from rival publications, whom he helped and guided – provided he considered them serious about their work. If you were in a war zone, trembling, you somehow felt safe if John Bulloch was by your side.

During his time at the Telegraph, despite its right-of-centre tradition, Bulloch remained almost fanatically objective, never pompous or pretentious. He cared first and foremost about the people he was writing about and, nine times out of 10, these were the poor, the stateless, the victims of dictators or wars. He wrote for the Telegraph's readers, not its bosses, and thus enhanced that newspaper just as he did this one. As for the old cliché about not suffering fools gladly, Bulloch would not suffer fools at all – be they princes, sheikhs, editors or young journalists he felt were "in the field" for their own glory.

Standing over six feet tall, slim, always immaculately dressed and with a shock of white hair ahead of its time, he strutted what foreign correspondents call the "movable village" – whatever war, coup d'état, natural disaster or other "nastiness" needed covering – armed only with a notebook but often facing down gunmen or soldiers.

Julian Nundy, at the time a Newsweek correspondent but later to join Bulloch at The Independent, recalled arriving with him at Cairo airport to cover the assassination of President Anwar Sadat in 1981. Tension was high and Egyptian security men demanded to know "what equipment" the two journalists were carrying. "I possess a very small pencil," bellowed Bulloch, cracking the security men into laughter. On that same story, Ed Steen, then working for The Sunday Telegraph, recalled Bulloch dictating his (Steen's) 2,000-word piece down the line to a copytaker in London because Steen had been exhausted by a frustrating journey from Kampala.

Steen, who would also later join us at The Independent, remembered a lunch – no food was usually involved in those days – at the King and Keys next to the Telegraph and therefore its 'staffers' "local". Bulloch's diplomatic editor at the time approached the big man and said: "John, I'm looking into a rather sexy little story in Gibraltar."

"There is no sex in Gibraltar, Norman," came the reply.

I was with Bulloch in southern Lebanon in the early 1980s, attempting to cross into Israel to get the other side of the story, when we were stopped by masked Lebanese gunmen, their AK-47s pointed at our groins. "Oh, don't be ridiculous. Put that thing down. We're going through," said Bulloch in loud English. He spoke decent Arabic but reckoned good old English would be more effective at that particular moment. We walked past the gunmen, and past bemused United Nations peacekeepers, into Israel at a considerable pace. For me, the pace was because I was worried about a bullet in the back. For Bulloch it was because that's the speed he always walked.

When Israeli troops shelled the journalists' beloved Commodore Hotel in Beirut during their 1982 invasion of Lebanon, it was Bulloch who persuaded a taxi driver, at considerable cost to the Telegraph, to drive up to the Israeli lines at Baabda, above the city, where he told the Israeli commander. "Cut this nonsense out!" The commander did so, and Bulloch got back down to the Commodore in time to finish his drink, with a free top-up from the bartender. He then proceeded to write 1,000 words of colourful copy to the Telegraph in no more than 45 minutes.

Had Tony Blair or George W Bush sat down with Saddam Hussein and demolished a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label – as Bulloch was wont to do – perhaps they might have realised that Saddam had nothing more than weapons of mass deception. Whether he was with mercenaries in the Congo, the Shah of Iran, the Sultan of Oman, the sheikhs of the gulf, British spooks, or Palestinian refugees, Bulloch came out with the story.

John Angel Bullock was born in Penarth, South Wales, just southof Cardiff, on 15 April 1928, and attended Penarth County School for boys. He said later in life that Bullock became Bulloch after his byline was misspelt early in his career by an editor who considered Bulloch the typical Welsh spelling. The "Angel,"for which he took some stick during his life, probably came from his father's travels as a merchant sea captain, including to South America and Spain where that male Christian nameis common.

A story that could only have come from John, but was never verified, was that his father, while a seaman, ran guns to the Republicans during the Spanish civil war. Some say young John, newly into the merchant navy, was with him, and that Barcelona was their destination. When you asked John to elaborate, you got the same twinkle in the eye. I don't believe he ever said to me "you don't really need to know that," but, strangely, it's a phrase that still comes to mind when I think of him.

As a teenager during the Second World War, young John watched British gun layers and radar operators set up camp in Nissen huts in his home town to track and shoot down Luftwaffe aircraft. He could not know then that he would look down many a gun barrel during his life but he, too, joined the merchant navy, first on the training frigate HMS Conway. He was caned many times for insubordination but it was during his time on the Conway that he first saw the Persian/Arabian Gulf which he would revisit as a correspondent and author years later.

He fought as an amateur boxer in the late 1940s before joining the Cardiff-based Western Mail newspaper as a reporter at the age of 23 for a salary of £8 a week. He went on to work for the Northern Daily Mail in Hartlepool, the national news agency the Press Association and, after a spell at the BBC, the Telegraph in 1958, where he would remain for 28 years.

While at the Telegraph's offices at 135 Fleet Street, Bulloch quickly became known for his intelligence connections. Secretaries at MI5 and MI6 were told to deliver any Bulloch article to their bosses before their croissants. His first book, Spy Ring, co-written with a fellow Telegraph correspondent Henry Miller, came out in 1961. Bulloch then wrote The Origins and History of the British Counterespionage Service MI5 (1963).

He went on to write breakthrough books about the Middle East. In The Gulf (1984), he described the rise of the Arabian Gulf nations, notably Dubai, which was still emerging as a city from the desert at the time. By explaining that nation and area to the world, Bulloch was hugely instrumental in bridging the cultural and religious gap which has seen Dubai transformed into a celebrity and tourist attraction today.

Later books included Saddam's War, co-written with the Independent correspondent of the time Harvey Morris, which largely predicted the events which would lead to Saddam's downfall and the loss of many British service personnel. More recently, along with another Independent Middle East expert, Adel Darwish, Bulloch wrote Water Wars, which predicted that water would be "the new oil" in terms of future Middle East conflict.

According to the Washington Post's Jonathan Randal, another great foreign correspondent of the era: "John was one of the rare colleagues I enjoyed meeting, especially in the diciest of situations. I knew he would make me laugh. And laughter and luck remain the war correspondent's best, and arguably only, friends."

It was while working for The Independent as Middle East editor that Bulloch and his wife Jill, both of whom knew, understood and loved Turkey, adopted an infant brother and sister from that country, Mehmet (now James) and Oya, in 1988. John is survived by Jill, his sons Adam and James and daughters Jilly and Oya.

John Angel Bullock (John Bulloch), foreign correspondent and author: born Penarth, South Wales 15 April 1928; married three times (twice divorced; two sons, two daughters); died Oxford 18 November 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments