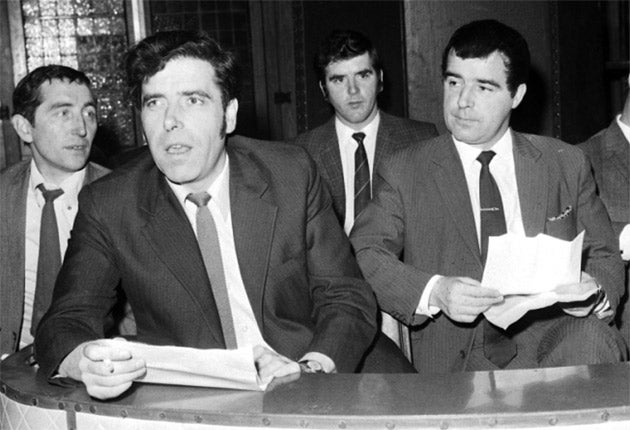

Jimmy Reid: Inspirational trade unionist who led the work-in at Upper Clyde which reversed government policy on the docks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jimmy Reid gripped the nation's imagination when he became the public face of working class opposition to Conservative Party policies in the early 1970s. Along with his friend and colleague Jimmy Airlie he led the "work-in" at the Upper Clyde shipyards in 1971 and 1972 which helped reverse the government's decision to close the yards.

The Amalgamated Engineering Union in those days had developed a "two-party system" of left and right. Even the right-wing general secretaries, Jim Conway from 1964-75 and Sir John Boyd from 1975-1982, exasperated though they might have been, developed a respect for the left wing of the union. In turn the left-wingers like Hugh Scanlon and his young Clydeside friends also developed respect for the tradition of the right. This meant that the union was a formidable force. Tony Benn told me yesterday that Jimmy Reid inspired the work-in and by his oratory created worldwide interest, with vivid pictures of him addressing mass rallies on Clydeside.

The ideas of Reid and Airlie were not only anathema to the government of Ted Heath, but also at first to Harold Wilson. Benn recalls that as a shadow cabinet minister who had been minister of technology, a huge government department, he went to Clydeside and pledged his support. "Harold was furious," Benn told me, "but then decided that he had better go up to Clydeside himself and see what was happening rather than rely on political colleagues such as the Shadow Secretary of State for Scotland, William Ross. The ex-prime minister, by then leader of the opposition, changed his tune and realised that the work-in led by Reid and Airlie was an extremely important event."

What Reid had done was to initiate a form of constructive protest which was far more difficult for governments to deal with than simply walking out away from the job. The hallmark of what Reid said in his moving speeches was that the dignity of workers demanded discipline and that it was their duty to continue production as far as they were able to do so. This attitude at the time was novel, and made a tremendous impression among those who would normally have been quick to condemn strike action.

Reid, always a generous man, repeated time and again that the organising brains were that of his friend Airlie, who in 1983 was to become the executive member of the AUEW responsible for Scotland. But it was Reid who supplied the necessary ingredient of oratory. He was far too intelligent ever to be a ranter and that was what gave him such a lasting impact. Years later, when Upper Clyde shipbuilding had ceased to exist, the memory of what Reid had set in motion became indelible in the history of the trade union movement.

I go back a long, long way with Jimmy Reid. In 1962 as Labour candidate at a by-election in West Lothian, I was opposed by the charming and able communist nurse, Irene Swan. At one of the hustings her supporting speaker was the young Jimmy Reid, then secretary of the Young Communist League, but well known in Scotland at that time for having led a much publicised strike of apprentices in the shipyards of the Clyde. After the hustings Swan and Reid came to talk to me and apologised for standing against me. "We would not have stood against you if we thought that there was any chance of your losing to the Tories," Reid told me, "but we think that it is our duty to the [communist] Party to stand in this democratic election." All his life Reid was personally courteous to those with whom he disagreed.

Some 40 years later my wife and I were invited to his 70th birthday hosted by himself and his ever-supportive wife, Joan, at the golf club at Haggs Castle in Glasgow. We found a number of guests who we never expected to see at the festivities of a great left-wing tribune. It revealed his capacity for friendship across political divides and the interests he displayed in cultural matters – far beyond those that might be expected of one who to so many was undeservedly a left-wing bogeyman.

At the 1964 general election I was opposed by Gordon MacLennan, later general secretary of the British Communist Party. Reid again came as supporting speaker and in conversation afterwards told me in very polite terms what he expected of the 1964 Labour Government. He was deeply serious and thoughtful and emphasised that in his opinion youth unemployment was a sin. However it was only later that he was to join the Labour Party.

One of the proofs that Reid was his own person was the huge anger he displayed against what he saw as the recklessness and foolishness of Arthur Scargill during the miners' strike. In 1959 Reid, as secretary of the Young Communist League, was one of those involved in a summer school attended by Scargill as a young man from the Yorkshire coalfield.

Reid recalled: "I have got no recollections of thinking, 'this is of great potential politically'. Scargill wasn't on very long. I cannot remember any significant contribution." The one thing he could remember was Scargill's passion for cars. "Scargill has always been fascinated with big cars," he told me with a smile. "He had bought a second-hand Jaguar and couldn't afford to run it." Reid added that Scargill's fascination did not evidently run to orthodox communist theory. "I have never seen Arthur Scargill, while he was in the YCL or subsequently, revealing any evidence of having studied Marx."

In 1984 there was a huge fall-out between the two ex-comrades. Reid made the interesting parallel between Scargill and Mrs Thatcher. "Those two deserve one another," he told me. "She has closed her mind to the possibility of being wrong; Scargill never admitted to having any doubts at all. He has that frightening certitude, like Mrs Thatcher. Although they are both apparently poles apart, politically, philosophically and ideologically, they are both dogmatists. The difference is that she has the whole state machine at her disposal."

In a devastating critique that confirmed the total political break with his former comrade, published some weeks before the end of the miners' strike, Reid wrote: "I reject the notion that Scargill is leading some crusade against Thatcherite Toryism. Beneath the rhetoric Scargillism and Thatcherism are political allies. I would put it this way: the political spectrum is not linear but circular. In my experience the extreme left always ends up rubbing shoulders with the extreme right. They are philosophically blood brothers."

Things might have been different, Reid believed. He said, "If only the manipulative Joe Gormley, president of the NUM, had allowed himself to be succeeded by Mick McGahey and not the hot-headed Arthur Scargill, the miners would have had more success and the British coal industry would have been saved. Whatever you think of the old communusts, they understood discipline, and what was possible and what would end in failure."

In 1979 he contested for Labour the Dundee East seat held by the parliamentary leader of the SNP, Gordon Wilson. Unexpectedly, because the SNP lost 10 seats that year, Reid went down by 20,497 votes to 17,978 with the Conservatives gaining 9,072, and the Liberals 2,317.

In the 1980s I and others tried to persuade Reid to put himself forward again as a Labour candidate. He declined, partly because he wanted to remain with his family in Scotland and partly because he had become an extremely good and well-read columnist. Harry Reid (no relation), one of the great editors of the Glasgow Herald, for whom Jimmy wrote a column and was television critic, told me: "Jimmy had the Glasgow way with words: he could make you laugh and cry and think in one sentence. Admittedly, he was sometimes fancy-free with the facts."

Reid remained a cult figure and was elected by the students as rector of Glasgow University. His rectorial address was hailed by the New York Times, who printed it in full, as "the greatest speech since the Gettysburg Address"

"A rat race is for rats," Reid said in his speech. "We're not rats. We're human beings. Reject the insidious pressures in society that would blunt your critical faculties to all that is happening around you, that would caution silence in the face of injustice, lest you jeopardise your chances of self-promotion and self-advancement. This is how it starts and, before you know where you are, you're a fully paid-up member of the rat pack. The price is too high. It entails the loss of your dignity and human spirit. Or as Christ puts it, 'What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul?'"

In the evening of his life Reid was a fierce opponent of the war in Iraq and warned that no good would come of military involvement in Afghanistan. It was partly on account of his exasperation with New Labour, particularly on foreign policy, that he left the Labour Party and in 2005 became a card-carrying member of the Scottish National Party. This in no way injured the friendship that many of us in the Labour Party had towards him. He was a human being enormously intelligent, and lovely in his personal relations.

Tam Dalyell

James Reid, trade union activist, politician, journalist and broadcaster: born Govan 9 July 1932; married Joan Swankie (three daughters); died Greenock 10 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments