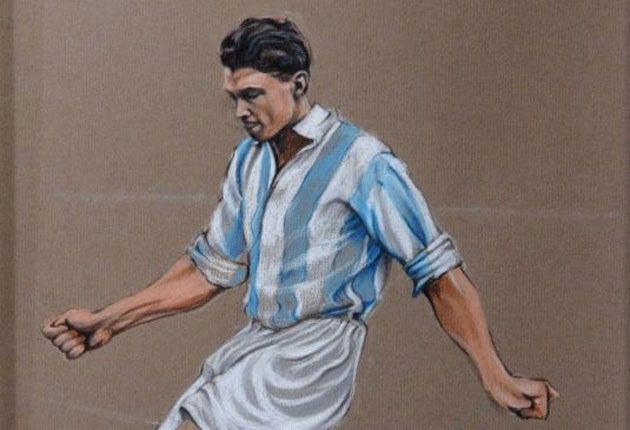

Jeff Taylor: Footballer who went on to forge a career as a popular singer and inspirational teacher

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the early 1970s Radio Three broadcast a most unusual talk.

It began with a Bellini aria, sung by Maria Callas, which faded intocommentary on a Bobby Charlton goal. "Whatever could be the connection?" Neilson Taylor, the well-known baritone, then asked. In an earlierlife he had been Jeff Taylor, the quick-footed centre-forward for Huddersfield Town and Fulham, and for 10 minutes he explored the affinities between the two activities: the muscular control, the self-discipline, the poise and balance. "Certainly for me," he concluded, "football and singing are not so far apart."

His was a rare combination of talents, and his younger brother Ken was no less remarkable. Also a professional footballer for Huddersfield in the old First Division, he played cricket for Yorkshire and England and studied fine art at The Slade. The two of them were like gentlemen amateurs from the Edwardian age, yet they came from the humblest of backgrounds in the Primrose Hill district of Huddersfield. Their father struggled to find work through the 1930s, and they lived in a small terraced house where, till he was 15, Jeff shared a bed with his younger brother.

Jeffrey Neilson Taylor was born in 1930 into a working-class community that valued music. "You were an outsider," he said, "if you didn't sing." Every Sunday evening after chapel the choir would gather around a piano at somebody's house, and as a boy soprano Jeff won a talent contest in Greenock Park with a rendition of the Victorian hymn "The Holy City". He also had a taste of popular entertainment when as a boy he accompanied his grandfather to Blackpool beach for his Punch and Judy show. Jeff's task was to attract a crowd by performing a tap dance on a small mat.

He scored goals aplenty in junior football – 62 in nine matches in the local under-15 league – and, after attending Almondbury Grammar School, he was signed by Huddersfield Town. He scored on his debut against Chelsea in November 1949, and he used his wage of £6 a week to support himself through a geography degree at London University, travelling each Saturday to meet up with his team-mates. In two years he played 71 matches, scoring 29 goals.

One football magazine tipped him for international honours. "Taylor," it wrote, "is only of medium build buthe moves like quicksilver, has good ball control and is very dangerous anywhere near goal with either foot or head." His university professor advised him to cut back on football in his final year but, instead, Jeff gothimself transferred to Fulham, who paid him a £10 signing-on fee. Theclub was known for its showbusiness atmosphere: the chairman Tommy Trinder was a popular comedian,and the board also included Chappie d'Amato, the bandleader. "It wasmore of a Christmas club than a football club," Jeff said. "A fun club. Not at all like Huddersfield. I felt very much at home."

Fulham were relegated to the Second Division, but they had a forward line of rising stars – the future England captain Johnny Haynes, the future England manager Bobby Robson and the ever-loquacious Jimmy Hill, who would become the face of football on television. Taylor stayed with them for three seasons before moving to Brentford, where he became club captain.

All the while he continued his studies. He trained to be a schoolteacher, but an unhappy placement at Chiswick Grammar School convinced him that he was on the wrong path. "They put me to teach a class ofsix sixth-form girls, and it frightened me to death. I didn't know anything about girls."

He remained an active amateur singer. Once, after a match at Liverpool, he hurried off to sing the baritone lead in Merrie England with the Colne Valley Male Voice Choir, and he was prominent in the university's Music Society. So, when teaching no longer appealed, he applied to the Royal Academy of Music, where he began training as an opera singer.

His football ended one Saturday in December 1956 when his cheekbone was fractured in a Cup tie against Crystal Palace. He stayed on the pitch, scoring a late goal, and was sent for plastic surgery to East Grinstead. "I had to go down on my own on the train, and nobody in the club got in touch till Tuesday." All his life he had a numb nerve from the operation, and he decided to call it a day as a footballer, resisting Brentford's offer of a £1-a-week pay rise.

The Brentford chairman Vic Oliver offered him work on his radio variety show Band Box, and this led to years with the Cliff Adams Singers, on Friday Night is Music Night and Sing Something Simple.

By now he was Neilson Taylor, his working life taking in both light music and opera. One time he was in Australia, training a backing group for Tommy Steele; another he was at Glyndebourne, playing Arbace in Mozart's Idomeneo alongside a young Italian tenor on his first visit to England, Luciano Pavararotti. He spent a year in Mantova in Italy, studying with Pavarottis's teacher Ettori Campogalliani, and this led to opera work in Covent Garden and Rotterdam.

The promise of those early years was never fulfilled. When his performance as Montfort in Verdi's Sicilian Vespers was rereleased a few years ago, one reviewer wondered why, with such a fine voice, "his tone so rich and secure", he was not a household name. Perhaps, as with his football, he lacked a little in self-belief, and he was not helped when his Yorkshire stubbornness led to a dispute with an influential impresario.

He found his calling in 1974 when he became Professor of Singing at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music in Glasgow, staying there for 18 years and coaching several singers, male and female, who went on to greatness, notably Anthony Michaels-Moore, Iain Paterson and Simon Neal. He was an outstanding teacher, a perfectionist who understood the technicalities of singing and the individual requirements of each of his students. Through his will he has established a fund to help young singers at the start of their careers.

Neither of his two marriages lasted, but he enjoyed many friendships in his final years which he spent amid the beautiful countryside of the Holmfirth area, south of Huddersfield. He despaired somewhat of the cynicism of modern football, but he never grew weary of the company of musicians. Several of them continued to visit him for coaching, even in his last months when he was very ill. For years Michaels-Moore, wherever he was singing a leading role, would fly Taylor out to hear the final run-through.

From the terraced house inPrimrose Hill to the roar of the crowd at Fulham's Craven Cottage, fromthe Methodist chapel choir to the opera at Glyndebourne, he movedfar beyond the horizons of his parents' world. "But I'm still a Yorkshireman," he would say proudly. "Whatever I've done, nothing has knocked that out of me." His brother Ken, a working artist, survives him.

Jeffrey Neilson Taylor, footballer, singer and teacher: born Huddersfield 20 September 1930; married twice; died Holmfirth 28 December 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments