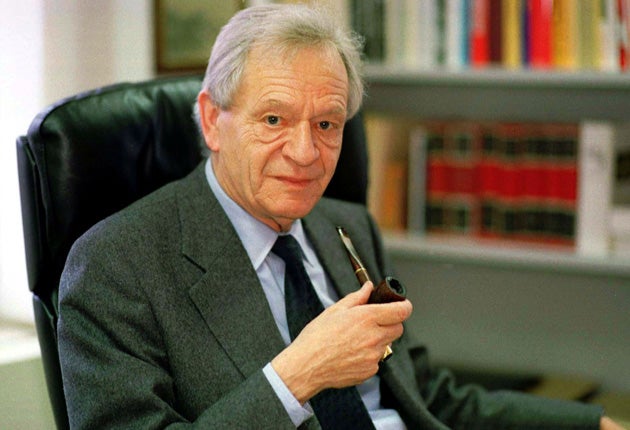

Jean-François Bergier: Historian whose commission exposed Swiss wrongdoing during the Second World War

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jean-François Bergier was a respected Swiss historian who exposed his country's dark deeds during the Second World War. He led the Independent Commission of Experts (ICE), which was set up in December 1996 by the Swiss parliament and given a wide range of powers to examine neutral Switzerland's relationship with Nazi Germany during the war. The investigation came about following a scandal involving dormant Swiss bank accounts belonging to victims of the Holocaust. There was much criticism from Jewish groups, particularly in America, that Swiss banks had made it difficult for heirs of Holocaust victims to claim assets deposited by their relatives. The saga became a huge national embarrassment and received worldwide coverage, much to the annoyance of the Swiss authorities.

The ICE's mandate was to investigate the volume and fate of assets moved to Switzerland before, during and immediately after the war. With about 100 staff at their disposal, the report took five years to complete and contained 27 volumes. Published in 2002, the report was damning, shattering many myths about Switzerland's wartime history.

Bergier's team of nine historians from Switzerland, the United States, Israel, Britain and Poland found that government and industry had co-operated with the Nazis, and that Switzerland had turned away thousands of Jewish refugees at its borders. The report, named after Bergier, concluded that Switzerland "became involved in [Nazi] crimes by abandoning refugees to their persecutors", even though the Swiss government knew by 1942 of the Final Solution, and that rejected refugees would face probable deportation and death. It also destroyed the idea that Switzerland's defences had saved it from Nazi invasion, and highlighted the uneasy relationship the Swiss had maintained with Germany. The historians also criticised the banks' failure to return Jewish assets after 1945, but said it resulted from poor judgement and a desire to safeguard Swiss banking secrecy rather than pure profiteering.

Upon presenting the commission's 11,494-page report Bergier said, "Large numbers of persons whose lives were in danger were turned away – needlessly. Others were welcomed in, yet their human dignity was not always respected." This policy contributed to "the most atrocious of Nazi objectives – the Holocaust," he added. It was reported at the time by the Swiss media that the country's "hero image changed, almost overnight, to that of villain."

Bergier was disappointed by the Swiss government's response; it seemed to want to emphasise what the report said had not been proven, namely that Swiss aid to Nazi Germany had helped to prolong the war, that deportation trains had travelled through Switzerland, and that assets from Jewish victims had made a major contribution to the Swiss banking system. On the whole, Bergier saw the authorities as attempting to ensure that the reports made "as little noise as possible" rather than stimulating much needed debate and further historical research. None the less, following the report, the Swiss government formally apologised to Jewry for its Second World War policies.

The son of a pastor, Jean-François Bergier was born in Lausanne in December 1931. His family had left Italy before his birth, following the rise of Mussolini. Bergier studied at the University of Lausanne and graduated with a degree in humanities in 1954. He also studied in Munich, Oxford and Paris. In 1963 he gained his doctorate and in the same year became Professor of Economic History and Social Economics at the University of Geneva, where he remained until 1969, when he became Chair at the Zurich Federal Polytechnic. He remained there until his retirement in 1999. He was also a visiting professor at the Sorbonne from 1976 until 1978.

After accepting the government's offer to lead the commission in 1996, he recalled, "everything changed, including my private life. I couldn't escape it for a moment." It was noted by friends and colleagues that Bergier was under enormous pressure during the five-year investigation and that smoking his pipe was one of the few releases he had for the stress.

In the end, the commission was unable to give an exact number of Jews turned back; however, estimates are as high as 30,000, with about the same number allowed in. The exact numbers have been the subject of a continuing emotional debate in Switzerland, the wartime generation reacting furiously to the Commission's findings. While some Swiss citizens did help, a "more flexible and magnanimous attitude" would have allowed many Jews to escape death, Bergier concluded.

The international dispute over the Holocaust accounts was defused somewhat, and a certain degree of guilt acknowledged, when the country's biggest banks agreed to a $1.25bn settlement in August 1998. The banks were also forced to publish thousands of names on dormant wartime-era accounts to try to locate the owners or their heirs. Elan Steinberg, executive vice-president of the World Jewish Congress, who helped to negotiate the 1998 settlement, said of the report, "It warns that neutrality cannot be a watchword for callousness and insensitivity."

In 2007, reflecting on his role and on the report itself, Bergier said, "above all there's the issue of Switzerland's historical responsibility. You have to be responsible for your past. On that condition you can face the future clearly and calmly."

Martin Childs

Jean-François Bergier, historian: born Lausanne 5 December 1931; married (two sons); died Blonay, Switzerland 29 October 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments