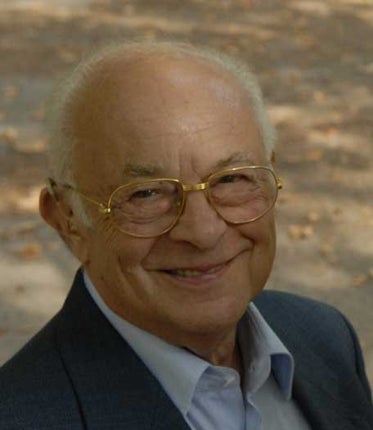

Jean Samuel: Auschwitz survivor who featured in Primo Levi's Holocaust masterpiece 'This Is A Man'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jean Samuel lived through and survived some of the very worst tortures of the Nazi Holocaust.

Although he remained silent about his experiences for many years, he came to wider notice for his part in one of the very greatest works of testimonial writing to have come out of the Holocaust, Primo Levi's This is a Man.

Born in 1922 in Wasselonne in the Franco-German border region of Alsace, Jean Samuel grew up in a close-knit Jewish family and community. His father ran the town pharmacy and Jean, too, would study pharmacology at university in Toulouse, after attending a lycée in Strasbourg.

After the occupation of France in 1940, Samuel and his extended family moved to live in Dausse in the Lot-et-Garonne region in south-west France, where in March 1944, they were betrayed and rounded up by the Gestapo. Along with seven other family members (of whom two survived), Jean was arrested and imprisoned in Toulouse and then Drancy, and from there deported to Auschwitz. For nine months he was interned in appalling conditions along with around 12,000 slave labourers, mostly Jews, in Auschwitz III (Monowitz), a satellite camp of the main Auschwitz-Birkenau complex, run by IG Farbenindustrie.

By pure chance, as he always insisted, he was still alive on 18 January 1945, when, shortly before the Soviet Army reached the camp, the Nazis forcibly evacuated all but a handful of prisoners on the horrifying death marches westwards, towards the rump of the Reich. Samuel crossed Poland and Czechoslovakia by foot and open convoy, reaching Buchenwald in late January. Many thousands died on the march, including, at the last, his uncle René. After more weeks of hard labour and violence, he was finally liberated by the American army on 11 April.

After his return to Alsace, in 1946 Jean married Claude and in 1950 he took up his father's job as town pharmacist. For many decades, he said little or nothing in public, or indeed in private, about his devastating experiences. He only began to take up the role of public witness in the 1980s, a role to which he became ever more devoted, speaking with great clarity and force at schools and commemorative events in France and more widely in Europe. On 27 January 2005, to mark Holocaust Memorial Day, he addressed the European Parliament in his local capital Strasbourg (his lecture is online at: http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/shh/samuel/jsfilm.htm ). And in 2007, he published his only book, written with the French historian Jean-Marc Dreyfus, entitled Il m'appelait Pikolo ("He Called Me Pikolo").

In his late career as an oral chronicler and educator about the Holocaust, Samuel was one of an heroic cohort of survivors, largely unsung and mostly now gone, who persisted through the post-war era and into old age in passing on to as many who would listen, above all the young, the terrible message from the concentration camps.

But he also had something extra to recount, a further, rather remarkable claim on our attention. It was his strange destiny – one he bore with great dignity and humility – to exist in the public eye, and for posterity, too, not so much in his own right, but instead as a "character" in someone else's book, a friend he had met in the dark days at Auschwitz. It just so happened that the friend was Primo Levi, the book he went on to write Se questo è un uomo ("If This is a Man", 1947). The chapter in which Samuel appears, in an extraordinarily moving and humane cameo, is the most famous of the book and of Levi's entire work, entitled "The Canto of Ulysses".

One of Levi's biographers, Carole Angier, sets its significance very high indeed: "If one day there is a new Holocaust, and we can save only one chapter of one book from the twentieth-century, it should be this one: Chapter II of If This is a Man, 'The Canto of Ulysses'".

Samuel had briefly shared a bunk with Levi's closest Italian companion in the camp, Alberto Dalla Volta, and then recalled being thrown together with Levi as they sheltered from a bombing raid. Both trained in chemistry, Levi and Samuel were then assigned to the so-called Chemical Kommando, part of the somewhat farcical pretence that IG Farben was running a rubber plant out of Monowitz. Jean was the Kommando's "Pikolo" (hence the title of his book) – that is, the youngest member and assistant to the Kapo, Alex, with certain responsibilities and privileges, including fetching the watery liquid that passed for nourishment.

As Levi accompanied him on one such occasion, as related in If This is a Man, Samuel asked him to teach him some Italian; and on a whim, Primo decided to recite and translate and explain to the patient and perplexed young Frenchman the greatest of all moments of poetry in Italian, Ulysses' speech to his crew in Dante's Inferno. In a crescendo of half-remembered fragments and almost delirious excitement, Levi and Samuel seem to stand on the verge of a great revelation about history, human nature and evil ("the reason for our fate, for our being here today"). But perhaps as important a rare bond of friendship, in this place of all places, is born out of the effort, a friendship that existed not only in the pages of If This is a Man but in reality also.

Levi wrote "The Canto of Ulysses" back in his native Turin in 1945 – according to another biographer, Ian Thomson, in one lunch break – assuming Samuel was dead. When he discovered through another survivor, Charles Corneau, that Samuel, too, was still alive, he contacted him, sent him the draft chapter, and they exchanged a series of moving letters reflecting on their duty to remember, and the strange friendship that bound them together.

They arranged to meet at the French-Italian border at Menton, but their papers were still in a mess, and so, somehow appropriately, these two young survivors struggling towards rebirth were allowed by officials to meet and talk in no-man's land, between their two countries, to get to know each other for the first time as "normal" human beings, and to reflect on how utterly changed they had been by what they had suffered.

Their friendship would last until Levi's death in 1987; and it is no coincidence that Samuel's own work as a witness took off after his friend's death, as if he were taking on the duty to remember they had talked about in 1946, now that Levi could do longer do so.

Jean Samuel, Holocaust survivor and pharmacist: born Wasselonne, Alsace, France 18 July 1922; married (two sons); died 5 September 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments