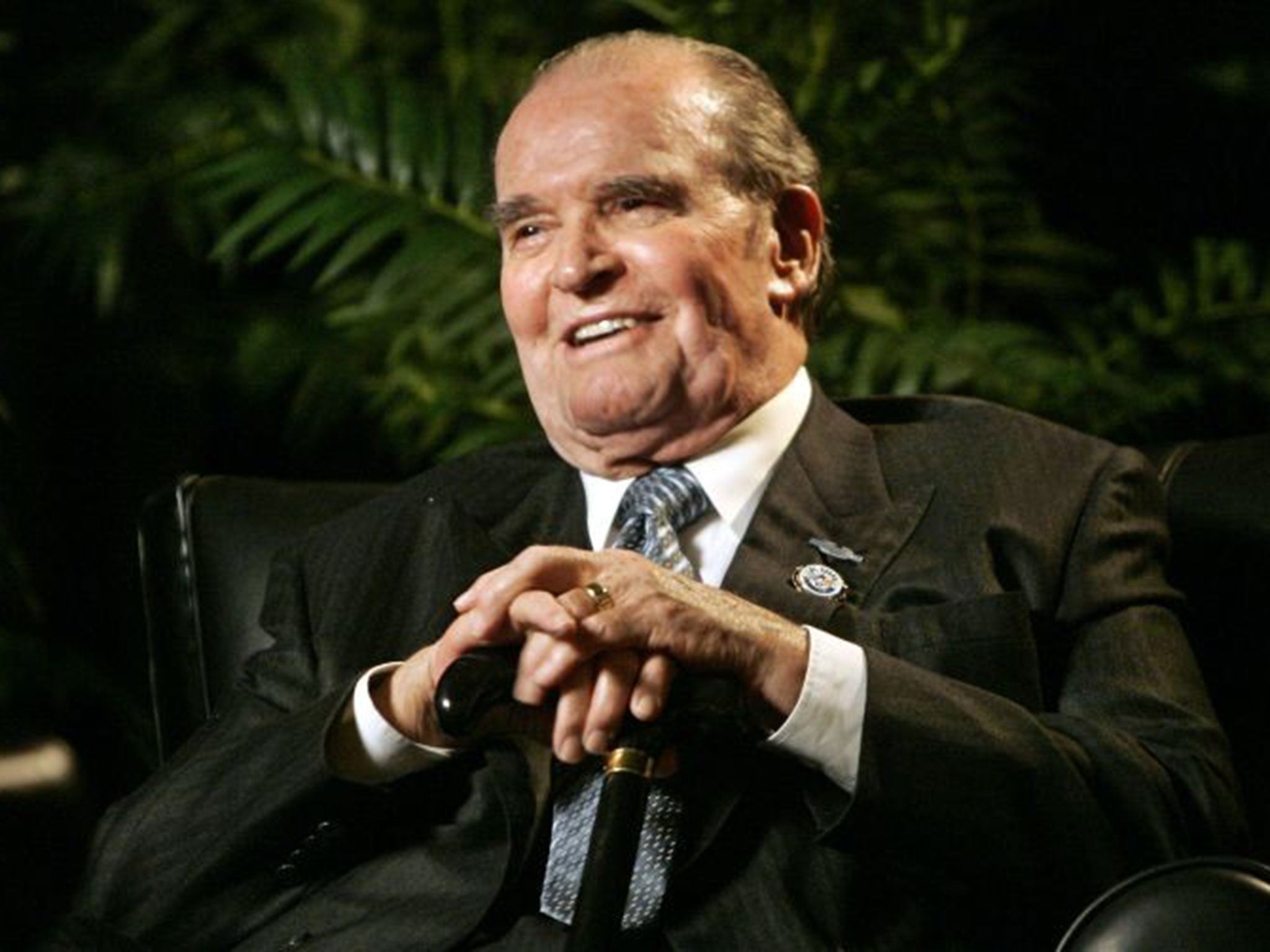

James Garner: The actor known for his portrayals of an honourable man in a dishonourable world

A look at the six-decade career of The Rockford Files star

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

For the majority of the 1960s and 1970s James Garner seemed to epitomise the honourable man in a dishonourable world that the American public in particular took to their hearts. But the public image so carefully cultivated thanks to roles like Maverick and private eye Jim Rockford, characters that worked because they were so close to the real person, hid a complex personality that even his most ardent fans wouldn’t have recognised, that of a man who suffered years of pain and a childhood of abuse, loneliness and deprivation.

He was born in 1928, the third son of Weldon and Mildred Baumgarner, in Norman, Oklahoma, where his father worked in the upholstery and carpentry business. His mother died when he was five, and with her went any hope of a traditional upbringing. For two years he and his brothers lived with a succession of relatives until their father remarried. But the young Garner despised his stepmother, Wilma, who used physical violence as a means of punishment. These mental scars, and the memory of being taunted as a child, left him with an acute inferiority complex that never truly left him. Even as a successful actor the fear of being laughed at still haunted him, which made his choice of profession in the first place, with its propensity for public humiliation, a curious one.

Finally his father divorced Wilma and headed for California, leaving his three sons to fend for themselves. Garner funnelled his pent-up aggression into sports, excelling at athletics and football, but at 16 left school to join the merchant marine, only to quit after discovering he suffered from sea sickness. Travelling to Los Angeles, where his father was running a carpentry business, Garner worked a succession of dead-end jobs until the Korean War, when he became the first draftee from his home state of Oklahoma. He served 14 months as an infantryman, was wounded twice and won a Purple Heart.

Discharged, Garner returned to Los Angeles, but found it difficult readjusting to civilian life. At 25 he was unsure what to do with his life so drifted back into menial work, until driving down a street one day he noticed a familiar name on an office plaque, that of Paul Gregory, with whom he’d worked as a teenager at a gas station. Gregory was now a theatrical producer and gave Garner a job in his production of The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial. During 1954 Garner appeared in hundreds of performances on Broadway and on tour, sharing the same stage as Henry Fonda, later a lifelong friend and, Garner once admitted, his greatest acting “teacher.”

He fell into acting by chance, but the profession curiously suited Garner’s personality. A self-confessed hermit, someone who preferred hovering on the periphery of society, he was able to observe his fellow man from a distance. But at auditions his introverted nature manifested itself in terrific nerves which he overcame by sheer willpower. He also eradicated his thick Oklahoma twang with the help of Charles Laughton, who advised him to read Shakespeare aloud on the beach and try to make himself heard over the waves.

With the knowledge that if he failed he could always go back to pumping gas or laying carpets Garner gave himself five years to make an impact. His dark good looks (he was part Cherokee Indian) quickly landed him small roles on television and eventually a contract with Warner Brothers. His film debut was in 1956’s Toward the Unknown starring William Holden. He was incredibly nervous but Holden boosted his confidence by declaring on set, “Jim, you’ve got something. You’re gonna be a big star.” Garner never forgot his generosity.

After he co-starred in a handful of mediocre films Warner Brothers put Garner into their new western TV series, Maverick. Playing a wandering gambler Garner perfected what became his trademark, the self-effacing charmer who solved problems more with his wits than his fists. In real-life, however, Garner’s temper, when aroused, which was fortunately seldom, became legendary in Hollywood circles. He once famously assaulted television producer Glen Larson (the man behind Battlestar Galactica), whom he accused of stealing scripts from The Rockford Files. “I only hit him with my left hand.” Garner explained later to a friend. When asked, “How come the left?” Garner replied, “If I’d hit with my right, I would have killed him.”

Maverick was a runaway hit and turned Garner into a household name, but it didn’t make him rich. Still under contract, he resented being paid peanuts for a show making millions. After three years he sued to break his contract. It was a huge gamble: Hollywood could have blacklisted him. Instead William Wyler cast him opposite Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn in The Children’s Hour (1961). More offers poured in and over the next nine years Garner made 20 films including The Great Escape (1963), Grand Prix (1966) and Marlowe (1969), where he played Raymond Chandler’s famous private eye and shared a memorable fight scene with a young Bruce Lee.

Coming comparatively late to acting, Garner never allowed fame to go to his head. He always viewed his career in terms of longevity, of staying the course. If you’re No 1 at the box office, he reasoned, there was only one way to go after that – down. But by the early 1970s his film career was less than healthy and so he returned to television and hit the jackpot with The Rockford Files.

As Jim Rockford, a private investigator who lived in a house trailer with his dad in Los Angeles, Garner won an Emmy award and a new generation of fans. For the next six years it was the most consistently successful show on American TV. But the price was steep; it left him mentally and physically exhausted and almost cost him his marriage when he separated from his wife for two years, a situation Garner blamed on the emotional toll of starring in a long-running series.

Garner walked away from The Rockford Files in 1980 and, echoing his time on Maverick, broke from his Mr Nice Guy image to successfully sue the studio for money he felt he was owed. Though he would never again find another role that brought him the popularity of a Maverick or Rockford, Garner never lost his appetite for work and was one of the few Hollywood stars who moved back and forth between film and television, winning Golden Globe awards and nominations in numerous mini-series and television movies and scoring big in the cinema with roles in the gender bender comedy Victor/Victoria (1982), returning to his roots co-starring with Mel Gibson in the big screen version of Maverick (1994) and Space Cowboys (2000), directed by HIS friend Clint Eastwood, whom Garner had known for 40 years, both having started out at the same time in TV westerns.

Throughout his career Garner’s forte was light comedy, and it worked best because here was a macho stud willing to make fun of himself. One critic called him his generation’s Cary Grant. Like Grant, Garner was never really taken seriously as an actor, not until 1985 and his Oscar-nominated performance in the romantic comedy-drama Murphy’s Romance. Yet he rarely took his own acting seriously, even on occasion belittling his talent. But cinema was the loser when he more or less semi-retired in the early 2000s, making a handful of appearances notably in the successful TV comedy 8 Simple Rules for Dating My Teenage Daughter, playing a maverick grandfather looking after three teenage girls when their father dies, and The Notebook (2004), as the husband of a victim of Alzheimer’s, a role Garner confessed was one of his most emotionally challenging.

Garner had that uncanny knack of making what he did on the screen look easy. He once said: “When people see me in something and say, “that’s just you – that’s not acting,” it’s the best compliment I can get.” His peers finally agreed, when in 2005 Garner received the Screen Actor’s Guild’s highest honour, a Lifetime Achievement Award.

James Scott Baumgarner (James Garner), actor: born Norman, Oklahoma 7 April 1928; married 1956 Lois Clark (two daughters); died Los Angeles 19 July 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments