Jacques Hétu: Composer whose modernist works never lost sight of traditional forms

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jacques Hétu died just too soon to enjoy the first performance of his Fifth Symphony, on 3 March, with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra under its chief conductor Peter Oundjian. But he did not want for public hearings: although his music is unfamiliar in Britain, he was one of the most frequently performed of all contemporary Canadian composers.

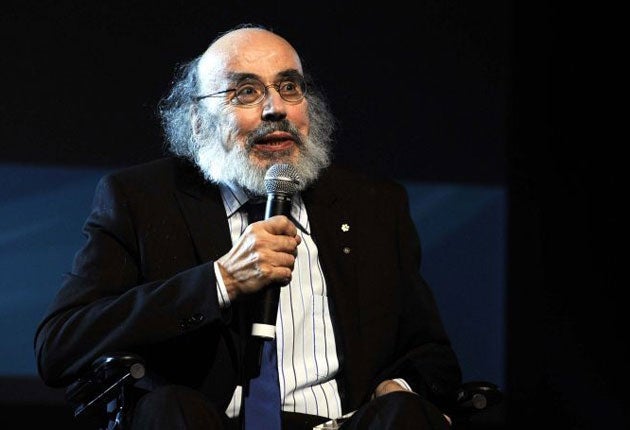

Despite a year-long battle with cancer, Hétu began 2010 on a wave, attending the first performance of his Concerto for Two Guitars and Orchestra on 14 January, and receiving a Prix Hommage from the Conseil Québécois de la Musique on 31 January, his Old-Testament beard and professorial pipe making him a familiar figure wherever he went.

Hétu was a late starter in music, taking up the piano only at 15 and composing prolifically soon after; it brought him relief from disruption in the family home. He began his formal musical education in 1955–56, studying piano, harmony and Gregorian chant with Father Jules Martel at the University of Ottawa before spending five years at the Montreal Conservatoire. There he broadened his abilities, studying composition and counterpoint with Clermont Pépin, and signing up for Jean Papineau-Couture's fugue class, though he never actually took it; there was also harmony with Isabelle Delorme, piano with Georges Savaria and oboe with Melvin Berman, while a summer course at Tanglewood in 1959 brought him under the aegis of Lukas Foss. He left in 1961 with prizes in composition, counterpoint and harmony.

In 1961 a mix of prizes and bursaries – first prize in a composition competition run by the Quebec Music Festival, a Canada Council grant and the Prix d'Europe – allowed him to continue his training in Paris, where he studied composition with Henri Dutilleux at the École normale de Musique (1961–63) and took Olivier Messiaen's analysis course at the Conservatoire national (1962–63). He wrote his First Symphony, for strings, just before he went to Paris; while there he composed his Second Symphony, a Prélude for orchestra and a trio for flute, oboe and harpsichord.

Back in Canada, Hétu began the career as teacher that ran parallel to his life as composer. He taught at the Université Laval in Quebec from 1963 until 1977, with courses in analysis and music literature; he introduced classes in composition and orchestration. In 1979 he joined the University of Quebec in Montreal, remaining until his retirement in 2000; in 1980–82 and 1986–88 he was head of the music department. Over those years he became an important factor in shaping the skills of the generations following in his wake.

Hétu's earliest influences, he said, were Schubert and Puccini, with his teachers Pépin and Dutilleux also inflecting his language. He explained that his music grew slowly, from small thematic cells, often in a slow movement, which would then expand outwards as he built up a work as a whole. Those cells could be chromatic, even atonal, but they were always set in a firmly tonal framework.

That allowed Hétu to have his cake and eat it: his music sounds modern without rejecting the tradition from which it emerged – although his refusal to write what he called "du Boulez" cost him the support of the modern-music establishment. Instead, his music has something of the angularity of Bartók and the astringent lyricism of Honegger; a keen sense of drama and colour gives it immediacy; and his readiness to invoke extra-musical images – as in the arresting and moving five-movement suite Images de la Révolution of 1989 – allowed audiences ready points of contact.

Musicians, too, took to his music from the start. His early Adagio et Rondo (1960) is one of the most frequently performed Canadian works for strings. Glenn Gould's iconic status in Canadian culture meant that his recording of Hétu's Variations for Piano of 1967 carried extra-musical punch, helping bring attention to the young composer. From then on Hétu enjoyed a steady stream of commissions. Major Canadian soloists came to him for something new for their instrument, explaining the unusual number – over 20 – of concertos in his output: works for piano (1969 and 1999), bassoon (1979), clarinet (1983), trumpet (1987), ondes Martenot (1990), flute (1991), guitar (1994), trombone (1995), marimba (1997), horn (1998), organ (2001), a triple concerto for violin, cello and piano (2002), a double concerto for oboe and cor anglais (2004), viola (2006) and, most recently, the Variations on a Theme of Mozart, in effect a concerto for three pianos (2009).

The choral Fifth Symphony was Hétu's Op. 81, the final addition to a voluminous vocal output that ranges in scale from songs to a one-act opera, Le prix (1992). A fondness for the poetry of Émile Nelligan produced the song-cycles Les Clartés de la Nuit (1972/87) for voice and piano/orchestra, Les Abîmes du Rêve (1982) for bass and orchestra and the choral Les Illusions Fanées (1988). Other large-scale pieces involving the voice are Les djinns (1975), for small and large chorus, six percussionists and piano, and the Missa pro trecentesimo anno for chorus, organ and orchestra (1985). There is also a generous quantity of chamber music.

Hétu's work, said the conductor Jacques Lacombe, "always bears a very personal signature". Singling out "his lyricism, his harmonic language, his sense of structure, the clarity of his orchestration", Lacombe described Hétu as "a real musician who knew how to write for musicians, without laying traps for them – not that his music doesn't present challenges or difficulties for its performers. But ... he always wrote well for the orchestra and that is doubtless one of the reasons that orchestral musicians take so much pleasure in playing his music and that he is one of the Québecois and Canadian musicians most performed both at home and internationally."

Hétu himself despatched the idea of any "Canadian" qualities in his music: he was a Canadian composer, he said, because he lived in Canada but the music would have sounded the same if he had lived in Australia.

Nevertheless, in 1990 it was Hétu whom Pinchas Zukerman chose to accompany the National Arts Centre Orchestra of Ottawa, taking the Third Symphony (1971) and Antinomie (1979) on a tour of Germany, Denmark and Britain. One sees why Zukerman might choose the Third Symphony: its driving energy makes it an ideal visiting card for a musical culture insufficiently appreciated outside Canada's borders.

Jacques Joseph Robert Hétu, composer; born Trois-Rivières, Quebec 8 August 1938; married firstly (two sons, one daughter), secondly Jeanne Desaulniers; died Saint-Hippolyte, Quebec 9 February 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments