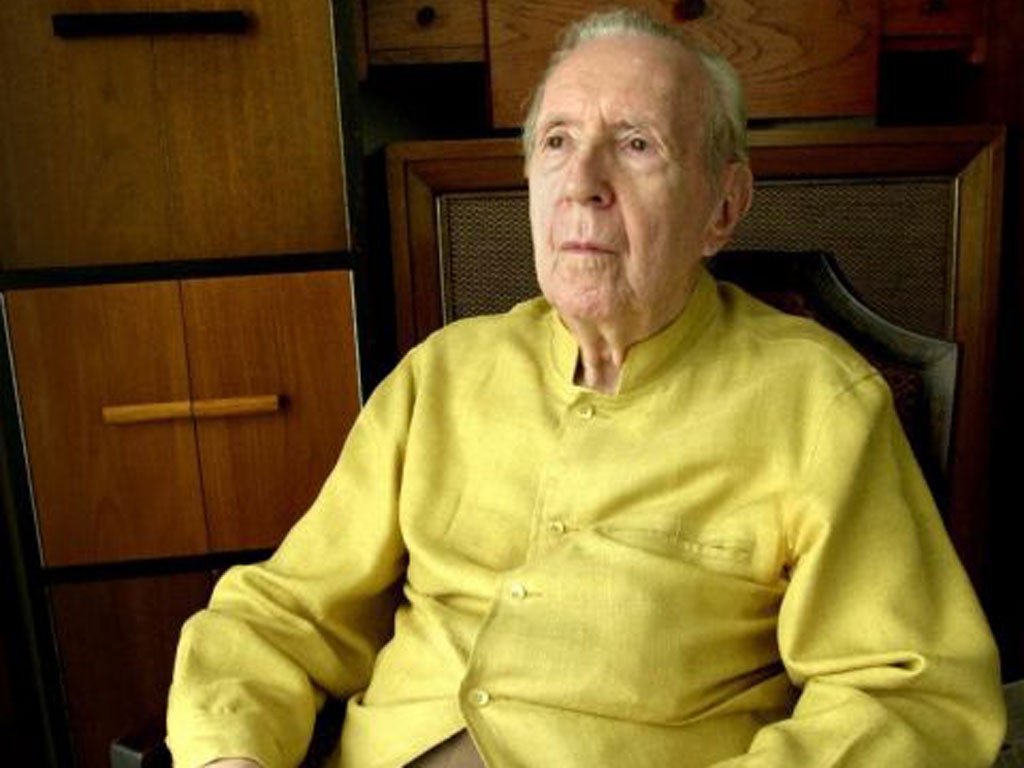

Jacques Barzun: Historian who believed that Western culture was descending into trivia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The long career of Jacques Barzun culminated in his publication, at the age of 94, of From Dawn to Decadence (2000) a survey of five centuries of Western cultural life in 900 pages, proving him the perfect don, yet a don who refused to imprison himself in a single subject. He wanted to share with others his relish for all that humanity has achieved, and wrote with authority in more than 40 books on Berlioz, Wagner, Hazlitt, Goethe, baseball and detective fiction, among many other subjects. His 1945 book Teacher in America, was regularly reprinted for 50 years. He had strong, original ideas about teaching, and once wrote that “there are more born poets than born teachers, something with which the spread of education has to contend.”

His rich father, Henri-Martin Barzun, was a writer, and at his home at Créteil, near Paris, had established l’Abbaye, a community of artists. So the boy grew up on Cubism, heard Stravinsky from his début, listened to stories that Apollinaire wrote for him and visited Duchamp’s studio. The advent of the Modern seemed to Barzun as he grew up just a part of the natural order of things. Art and the discussion of art were the only concern of all who counted in his universe, at least until the First World War and its aftermath. Perhaps it was this period that gave Barzun that controlled pessimism which tempered his otherwise Candide-like determination to seek out all that makes life delightful.

In 1920, his family moved to America, and by 1927 he had taken a degree at Columbia, with which he was to be associated ever after. While at work on a PhD he lectured in history, and in time became associate professor, dean of graduate faculties and provost. His power at Columbia went unchallenged.

Philip Lopate, a student there in the 1960s, wrote that he had asked Lionel Trilling for help over censorship of a magazine, and that Trilling had spoken to Barzun (“the Cardinal Richelieu” of the university) who assured him that the censorship was justified: “Barzun’s hunger for machinations and power was a campus joke ... We all knew that Trilling and Barzun had been close friends for years ... but that friendship had always puzzled me. Now I saw it as a kind of deal, with clear complicity on Trilling’s part. Barzun was his shadow, his worldly brother, who protected the senior faculty’s interests with administrative cunning, leaving Trilling free to continue his detached scholarly life.”

Not all Barzun’s time can have been absorbed in machinations: his shelf of books is rather longer than Trilling’s. The pull of history was stronger, though, and he was among those who helped invent the theory and practice of cultural history, that recognition of ideas and artefacts which exist in the marketplace and in circumstance.

His first book, in 1932, was The French ‘Race’: Theories of Its Origins and Their Social Implications, and he returned to the subject later in the decade, emphatic that dwelling on race ran counter to the human spirit, and quashed creativity.

From the start, perhaps as a result of his childhood, he could assimilate several points of view. In a life of 104 years he saw changes in taste, and the resurgence of artists after decline and eclipse. He was an informed populariser, at the vanguard of the mid-20th-century American vogue for the study of civilisations, and was an adviser to Life magazine: with WH Auden and Trilling, he formed a panel that chose books for the Reader’s Subscription club. In a spin-off, they had a television slot where, teacups in hand, they discussed the books: Edmund Wilson’s journal records watching when there was a great crash off-camera. He was later told Auden’s cup had contained neat gin and he had fallen to the floor. Barzun talked on unfazed.

As Carolyn Heilbrun wrote of him: “No picture of him I have seen ... captures either his physical or his inner qualities. With a taste for impeccable clothes (quite possibly the last man on earth to wear sock garters), he had neat hair and was given to studious speech ... he was not prone to sloppy, personal suffering.” He also had a rare ability to write against a background of administrative demands, even taking on such extra positions as being a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge.

Enough of Barzun’s works deal with specific matters, such as his monumental A Catalogue of Crime (1971), to show an interest similar to that of Edmund Wilson. Others could have easily made a book from the amount that Barzun put into an essay, such as his entry for the Journal of the American Medical Association about Thomas Beddoes, the great-grandfather of Gerard Manley Hopkins, who had been attendant on the ailments of Wordsworth and Coleridge. That eclecticism in depth was exemplified in his best, and best-selling, From Dawn to Decadence, which synthesised a lifetime’s study yet was no rehashing of old notes; its novel format had a boxed-off running commentary of contemporary quotations linked with, and just as rewarding as, the text of the main narrative.

There is no need to accept the thesis of its title, that culture is fragmenting into trivia, a subject Barzun had written about before in God’s Country and Mine (1954), in which he claimed that Walt Disney was “immortal for his black-and-white animated cartoons and lamentable in his vulgar fairy tales and fantasies in colour”. In Dawn he focused often on the way a place, incident or person can encapsulate a movement in history, showing, for example, how the 17th century revolution in science produced artistic forces. The book is full of detail, as vigorous as it is off-beat, comparing, say, the world of the Renaissance poets with Graham Greene. Perhaps administrative skill aids large-scale history. Barzun certainly knew how to get to the essence of a matter.

He was never a superhuman guru. Despite his formality, he was human, if only sometimes. Carolyn Heilbrun used to talk about detective stories with him, and, “one day Barzun asked me if I had any idea who Amanda Cross was... I told him I was. His astonishment was satisfying indeed. I had never before – and would never again – see him dumbfounded.”

Christopher Hawtree

Jacques Barzun, academic, historian and teacher: born Créteil, France 30 November 1907; married 1936 Mariana Lowell (died 1979), two sons, one daughter; married 1980 Marguerite Davenport; died San Antonio, Texas 25 October 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments