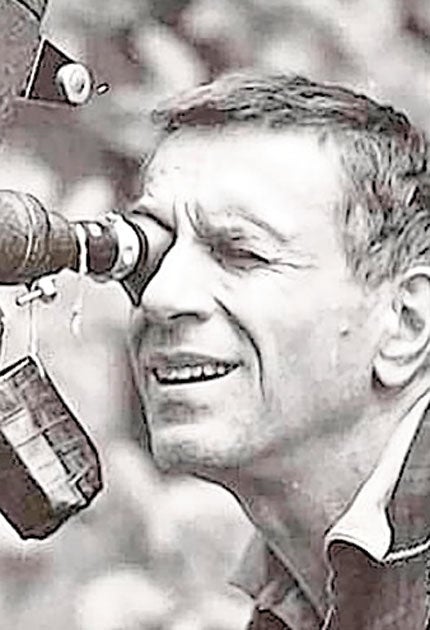

Gunnar Fischer : Bergman cinematographer best known for ‘The Seventh Seal’ and ‘Wild Strawberries’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Gunnar Fischer was the great cinematographer of Ingmar Bergman's early period, shooting 12 of his films in as many years and matching his move from the neo-realist Port of Call through the expressionist The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries to the theatrical The Devil's Eye.

After studying painting in Copenhagen and illustrating children's books, Fischer became a chef in the Swedish navy. An actress visiting the ship helped him join Filmstaden Studio as an assistant cinematographer in 1935. Fischer was strongly influenced by Gregg Toland's deep-focus photography on Citizen Kane, which allowed the viewer's eye to roam over the scene. But Carl Theodor Dreyer preferred intense close-ups of the actors' faces. Before they started Two People (Tva manniskor, 1945) Dreyer described Fischer's previous work as "milk and porridge" and the deeply shaken cameraman completely changed his style, employing strong modelling lights.

Fischer's first collaboration with Bergman was Crisis (Kris, 1946), an unhappy experience for both. The novice director saw the studio replace Fischer with Gösta Roosling, though he was a documentarist, happier on location. In fact Port of Call (Hamnstad, 1948), shot by Fischer at Gothenberg docks, does have a semi-documentary feel.

Bergman and Fischer agreed that they should never defer to each other, but be completely honest in discussing their work, though the director later intimated that his unyieldingness contributed to their parting. Bergman increasingly began to favour long takes, as in the portmanteau Thirst (Torst, 1948), though it made Fischer's job much harder as he sometimes had to light large sets through which the camera and actors could move freely.

In 1951 some Swedish film companies shut down in protest at high taxes and over the next two years the financially pressed Bergman made nine amusingly playful soap commercials with Fischer. The conflict also encouraged him out of the studio. The short and intense Swedish summer has inspired many directors, and features in the titles of three Bergman-Fischer films: Summer Interlude (Sommarlek, 1951), where Bergman felt he found his style; Summer with Monika (Sommaren med Monika, 1953) and Smiles of a Summer Night (Sommarnattens leende 1955).

Monika attempts to dispel that season's mythic idyll but its sexuality was strong meat even for Sweden's censor and was cut. For Smiles, an erotic comedy of manners, Fischer gave the velvet night a chillier edge. Along with the comedy Secrets of Women (Kvinnors Vantan, 1953) and The Magician (Ansiktet, 1958), Fischer's diamond-sharp images contrast with gloomy scenes to reflect the characters brittle relationships or their changing fortunes.

As Bergman's work became more expressionist, exteriors like the mythic wood in the medieval morality tale The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet, 1957) were often shot on the back-lot. Challenged that the film's most famous scene is cross-lit, making it seem asif there are two suns, Fischer responded: "If you can accept that there is a knight sitting on a beach playing chess with Death, you should be able toaccept that the sky has two suns."When Victor Sjostrom, the star of Wild Strawberries (Smultronstallet, 1957)was too ill to film inside a travelling car, Fischer had to use back projection though he felt that, with no time for tests, it came out badly and he hated the effect. Ironically, it adds to the uncanny atmosphere.

Fischer didn't enjoy making The Devil's Eye (Djavulens oga, 1960),feeling that Bergman was scapegoating him for the film's other failings.The director's taste was also changing and he wanted Fischer to change his sculptural style to something softer.It was their last collaboration and Sven Nykvist took his place for the next phase of Bergman's career. Despite aninvitation, Fischer did not return for The Silence (Tystnaden, 1963) as hewas working on Disney's Hans Brinker or the Silver Skates. He was lured back for the title sequence of The Touch (Beroringen, 1971).

Fischer's career was almost exclusively in Sweden. Among the other directors with whom he regularly worked were Lars-Erik Kjellgren and Alf Kjellin, who later carved out a career as a US television actor and director.

One of his few films with a foreign director was Anthony Asquith's Swedish-set Two Living, One Dead (1961) about the guilt suffered by the survivor of a violent robbery. Kjellin appeared in it and that year Fischer also shot the Kjellin-directed, Bergman-scripted Pleasure Garden (Lustgarden). In 1965 Fischer directed his one film, the short The Devil's Instrument (Djavulens instrument), a mysterious romance featuring a jazz bassist. In the mid-1970s he moved into television and, with his son Jens (both he and his brother Peter followed in their father's steps), worked on Jacques Tati's last film Parade (1974).

Erling Gunnar Fischer, cinematographer: born Ljungby, Sweden 18 November 1910; married Gull Söderblum (two sons); died 11 June 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments