Gillian Lowndes: Potter and sculptor noted for incorporating a wide variety of materials into her work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

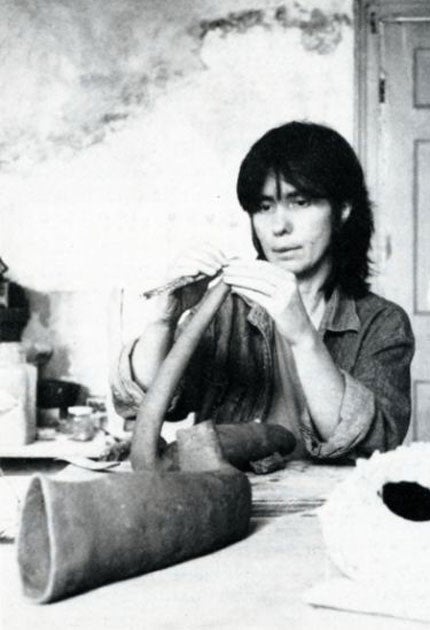

Your support makes all the difference.Although trained as a potter, Gillian Lowndes incorporated a range of other materials in her objects that took on all the strength and intrigue of sculpture. Taking an experimental approach that drew on a diverse range of objects that included traditional artifacts seen and collected in Africa, the detritus of everyday, as well as clay, Lowndes produced work that challenged perceptions of what clay could be and how it could be used to comment on waste, culture and tradition.

Much of her childhood was spent in India but she and her twin sister attended a private school in England where she showed an aptitude for art, which led to her studying sculpture at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. Although the school was generally viewed as progressive, the course involved much life-modelling, which Lowndes enjoyed, but she gradually found it too restrictive and drifted into the lively and more relaxed atmosphere of the pottery department. In the mid-1950s it was energetic and experimental, encouraging enterprise and innovation. Students were given a grounding in a variety of hand-building techniques, processes that Lowndes was to use throughout her life. It was there that she met her future husband and follow potter Ian Auld.

A year in Paris, where she attended the École des Beaux Arts and made pots in a garage, convinced her that clay was her medium, and on her return to London she shared a studio in Bloomsbury with Robin Welch and Kate Watts. Here her work was spotted by the gallery owner and entrepreneur Henry Rothschild, leading to a solo exhibition at Primavera in 1961 where she showed, among other forms, pinch pots. The exhibition marking the start of a new body of work using techniques such as pinching, coiling and slabbing with forms including tall slender vessels and wall pieces.

In 1966 she moved with Auld to Wiltshire, where she taught at Bristol Art School and continued to hand-build. The offer to Auld of a two-year research scholarship in Nigeria in 1970 was too attractive to turn down. Africa proved a revelation: close encounters with the traditional artifacts of the country, be they pots, textiles, shells or beads, brought a new appreciation of their beauty, both potters falling in love with such objects.

Auld became a thoughtful and sensitive dealer in ethnographica, their home filled with masks, textiles and artifacts. The work was to have a profound influence on Lowndes' ceramics in that it introduced a freer approach to making, and the idea of combining other materials. In Nigeria she produced ceramics made from local clay and fired in a bonfire.

Back in England they settled in London, where Lowndes taught at Camberwell and the Central, where she was respected as a thoughtful and encouraging teacher. Inspired by her experience in Africa, Lowndes used clay to replicate such things as the appearance of rope or the smoothness of quills, each piece laid on top of the other in the manner of basketwork. Dry glazed surfaces in muted colours, made largely from wood ash, suited the forms.

In the late 1970s Lowndes made the breakthrough that has come to define her work when she started to incorporate non-conventional materials into her objects, most notably fibreglass tissue dipped in porcelain slip in an attempt to capture the appearance of bark cloth, a material that has ceremonial use in Samoa and Fiji. Forms included bag-like shapes set on bits of old bricks and wall pieces that rested on foam rubber. These, she described, as "melting my own organic mass". Shown in the 1979 touring exhibition "State of Clay", the new work confirmed Lowndes's status as a leading innovative potter and sculptor.

As the forms developed so the range of materials broadened to include glossy Egyptian paste, 18th-century brick, nichrome wire, bits of broken cup, granite chips, bulldog clips, curled bus tickets and wire mesh, the clay acting as a "glue" to hold the form together. One series was based on American Indian quivers, the shapes of horns and a motif she called "Tail of the Dog", derived from a pattern seen on an appliqué wrapper from the Congo.

Undeterred by the high failure rate, Lowndes looked and learnt, relentlessly pursuing new directions. Her eye was later caught by the familiar shapes of sardine tins, loofahs dipped in clay slip, forks and can-openers. A high profile solo exhibition, New Ceramic Sculpture, at the Crafts Council Gallery in 1987, proved a revelation in demonstrating Lowndes's talent to amaze and engage with table- and wall-based pieces that combined the literal with the metaphorical, all intriguingly linked to the processes of ceramics.

After a period of living in Toppesfield in Essex and following the death of Ian 10 years ago Lowndes moved to an 18th-century house in Spitalfields, restoring the building, setting up a studio and cleaning up the garden. In the process she discovered fragments of bricks and other objects that became part of her work, a sort of autobiography that reflected her concern with where she lived.

Increasing ill-heath prevented her making extensive use of the studio but the final pieces had lost none of her power or verve. Quiet and intense, Lowndes' seeming reticence disguised a sharp and penetrating intelligence. Once describing herself as "a bit of an outsider", she was an uninhibited investigator of material, metaphor and allusion. Her work is in many major collections including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Crafts Council Collection.

Gillian Marjorie Lowndes, potter: born Kirby, Cheshire 19 June 1936; married Ian Auld (one son); died London 2 October 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments