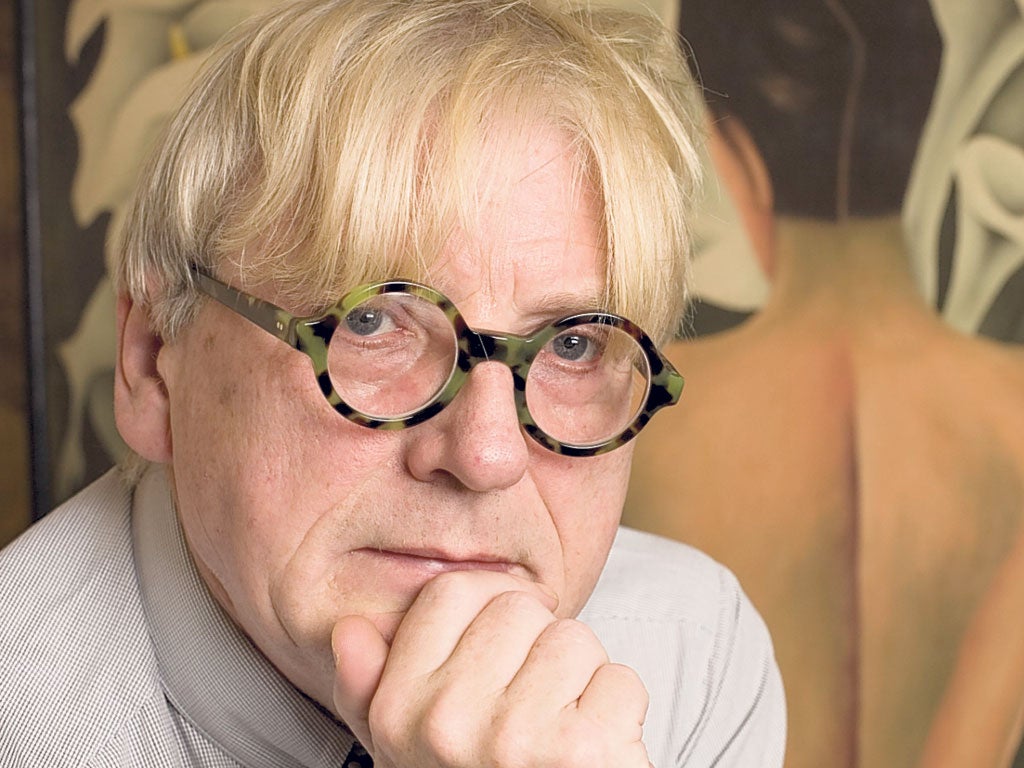

Gilbert Adair: Novelist, critic and screenwriter whose work shone with wit and playfulness

An author has died. Let us begin to quote him. "Have I any posthumous last words?" Gilbert Adair asked at the end of his 1992 novel, The Death of the Author. "Not really. As I have discovered to my disappointment, death is merely the displaced name for a linguistic predicament, and I rather feel like asking for my money back – as perhaps you do too, Reader, on closing this mendacious and mischievous and meaningless book."

That is typical of Adair's wit and playfulness, and his lifelong attempt to extricate feeling from the congealed theories of literature and cinema and being helplessly post-modernist. In what may be the book that most fully expressed Gilbert, he wrote as follows: "In Reflections on The Name of the Rose, the little volume that Umberto Eco wrote to explain the genesis of his best-selling novel, there is a brief essay on postmodernism from which I never tire of quoting. Eco defines the postmodern attitude in this way: 'as that of a man who loves a very cultivated woman and knows he cannot say to her, "I love you madly", because he knows that she knows (and that she knows that he knows) that these words have already been written by Barbara Cartland. Still,' continues Eco, 'there is a solution. He can say, "As Barbara Cartland would put it, I love you madly." At this point, having avoided false innocence, having said clearly that it is no longer possible to speak innocently, he will nevertheless have said what he wanted to say to the woman: that he loves her, but he loves in an age of lost innocence. If the woman goes along with this, she will have received a declaration of love all the same.' "

That comes from Flickers: An Illustrated Celebration of 100 Years of Cinema, published in 1995. I just hope it's still in print, because it may be the best book to give a smart child, an insomniac grandparent or a cultivated woman who realise they know nothing yet about the movies, so perhaps the time has come. You may not credit this, but the paragraph I quoted, with quotation marks I had to check over again, as if they were motes in a mirage, serves to introduce Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, the film Gilbert chose to represent 1992 in a survey – one still and a page and a half of text – that reaches from the Lumiere brothers' Workers Leaving a Factory to Ed Wood.

Gilbert Adair, 1944 to 2011, died last week of a brain haemorrhage, days short of being 67. He was born in Edinburgh. He lived in Paris through the '70s. He wrote. He wrote for a time as film critic for the Independent on Sunday, and it was my honour to be on the same page and to meet him a few times. He was a wisp of man. I only knew him with white hair. And he liked to seem waspish, acerbic, bad-tempered, lofty, and he could be convincing sometimes, though I don't think he was ever persuaded or quite sure what he was as a person. So he was a writer. He wrote articles, and reviews and columns, but he wrote books – as a rule, short books – and they were filled with his amusing, amused, learned, interrogatory tone.

He was restrained, or forgiving, about how much he wrote. The list is hard to believe for so young a man. I have never read it, or seen it, but he had done a parody of Alexander Pope called The Rape of the Clock. There were two books that took off after the conclusion of children's classics: Alice Through the Needle's Eye and Peter Pan and the Only Children. There was Hollywood's Vietnam, the only one of his books I know that was remotely conventional and felt like an assignment. There were two non-fiction books, Myths and Memories and The Postmodernist Always Rings Twice. He had translated the correspondence of François Truffaut, and also undertook the translation of George Perec's book, A Void, which is composed without use of the letter "e". There were also novels: The Holy Innocents, The Death of the Author and Love and Death on Long Island, and his three Agatha Christie pastiches, beginning with The Act of Roger Murgatroyd in 2006.

Richard Kwietniowski made a film of Love and Death... and Bernardo Bertolucci did a movie called The Dreamers that comes from The Holy Innocents. Gilbert did the scripts for both, and he wrote several scripts for Raoul Ruiz: The Territory, Klimt (he only translated that one), and A Closed Book, based on his own novel, which opened in 2010. Gilbert knew enough film history to be very wary of what happened to either the novelist or the screenwriter when a picture was made. He might sigh over the end product but I suspect he was proud of them all just because he understood the sweet cut between the years of ordeal and compromise in putting any film on the screen, and the inevitability it had once there, whether it was good or bad.

He was a natural contrarian: I never got him to admit that Mitchell Leisen was more than an interesting but minor director – and I suspect he was right. If I had proposed that Leisen was lightweight, he would probably have adopted a view of greatness on his behalf. Not that he didn't take appreciation and value seriously. Still, I think that he was not quite a natural, journalistic reviewer. He was too interesting for that and too inclined to take an idiosyncratic direction. Introducing Flickers, he promised not to write anything like a history: "Its ambition," he said, "is the rather more modest one of celebrating, and at the same time interrogating, an unashamedly personal selection of images from a century of cinema, images which have spoken to me over the half-century of my own life..."

I believe that it was his great wish to write a book about Jean Cocteau that might have been large. I was going to say definitive, but Gilbert would have avoided that. He also had Anthony Burgess's words ringing in his ears – a review of The Holy Innocents that said, "manifestly in the tradition of Jean Cocteau's Les Enfants Terribles, considered a masterpiece, this is a far better book."

I was going to say that Gilbert Adair was irreplaceable, but that somehow suggests that he knowingly took up a central and necessary position, whereas until he came along no one could have dreamed of being Gilbert, or close to him. He was out there on one wing or another, and like winged creatures he flew. He was magisterial and cheeky, a believer and irreverent, So remember those children, grandparents and cultivated women and start them off with Flickers.

I'm going to quote again. This is what he said about Orson Welles: "... he was the life and soul of the cinema, as of a party. He was the medium's only actor-manager of the old, flea-bitten Henry Irvingish school, overacting in other people's bad movies, overdirecting his own masterpieces and, as it were, overliving his own life. His curse, yet it was arguably also his salvation, wasn't merely to have been interrupted, like Coleridge, by a person from Porlock. It was, wilfully, perversely, to have chosen Porlock – in a word, Hollywood – as the place in which to build his Xanadu."

Gilbert Adair, a writer – "overdirecting his own masterpieces"! Four words that just get Welles, with an accuracy that never buries fondness. An author has moved on. Read him.

***

The first time I ever encountered Gilbert Adair's work was in the early '80s, when he was a regular contributor to Sight and Sound, where his dazzling, thousand-angels-dancing-on-the-head-of-a-pin prose stood out among most of the other worthy contributors like an opera singer at a dentist's convention, writes Kevin Jackson. His deliriously subjective review of Coppola's The Outsiders introduced me, and doubtless the majority of other readers, to the anatomical term "incisive fossa" – that small, generally unremarked bump between the upper lip and the nostrils. Gilbert was eloquent and yearning on the fossa of one of the attractive young men in the film, and he fantasised about running up and down that bump in trainers.

I was hooked, on the gorgeous prose if not the sentiment, and hungrily hunted down all his other film reviews. At the time I was working as a producer on the Radio Four programme Kaleidoscope, so I invited him to review movies and plays and books for me.He proved as deft a broadcaster as he was a prose stylist; and we gradually became friends.

Though I was well aware that Gilbert could be difficult – he took offence easily, and was at times as mopey as Eeyore – I was lucky enough never to offend him, and can honestly say that his company was always charming. Every time we met, he would casually let slip some new area of arcane knowledge, from, let us say, the Soviet silent cinema, to all but forgotten minor American composers such as John Alden Carpenter. His tastes were mostly mandarin, and fastidious: he loved modern French poetry, and the giants of European cinema, but he had a lynx eye for excellence in the popular arts, too: he loved Tintin, and The Simpsons, and Chaplin. One of his most moving articles bore the typically apt yet ingenious title "On First Looking Into Chaplin's Humour".

Above all other qualities, Gilbert was, simply, delightfully intelligent. He was always keen-witted, and playful, and he relished both serious debate and playful intellectual sparring. A heavy smoker, he used to assert that cigarettes made one more intelligent. (Yes, there was a touch of Wilde about him.) In much the same way, simply being in his company could give you the impression that your own IQ was on the rise.

In some respects, he was more Parisian than British – or, to be exact, than Scottish, as he grew up in Edinburgh, and kept a trace of the city's accent. He had lived in Paris for much of his twenties, and had been stimulated by the writings of Barthes, Derrida and company without becoming a mindless, humourless slave to them. His critical essays owed something to the example of Barthes, but they had a richer comic sense, and an impishness that was all his own.

Memories to cherish? The shy, almost boyish grin on his face when a crowd of us applauded him at the launch of his first novel, The Holy Innocents. The lunch at which he read a few of us some extracts from A Void, including his "translation" of "The Raven" by Edgar Allen Poe into "Blackbird", by Arthur Gordon Pym. (We applauded then, too.) The long train journey, when we mutually confessed to a liking for the short stories of JD Salinger. The evening when, almost 20 years after we first met, he finally told me he was gay, and I tried to seem surprised.

Gilbert once said that he wanted to write in the same spirit with which Fred Astaire danced. Well, he pulled it off. He was always graceful, always entertaining, always staging apparently impossible verbal stunts. Without him the world seems less agreeable, less interesting, less bright.

Gilbert Adair, writer: born Edinburgh 29 December 1944; died London 8 December 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

4Comments