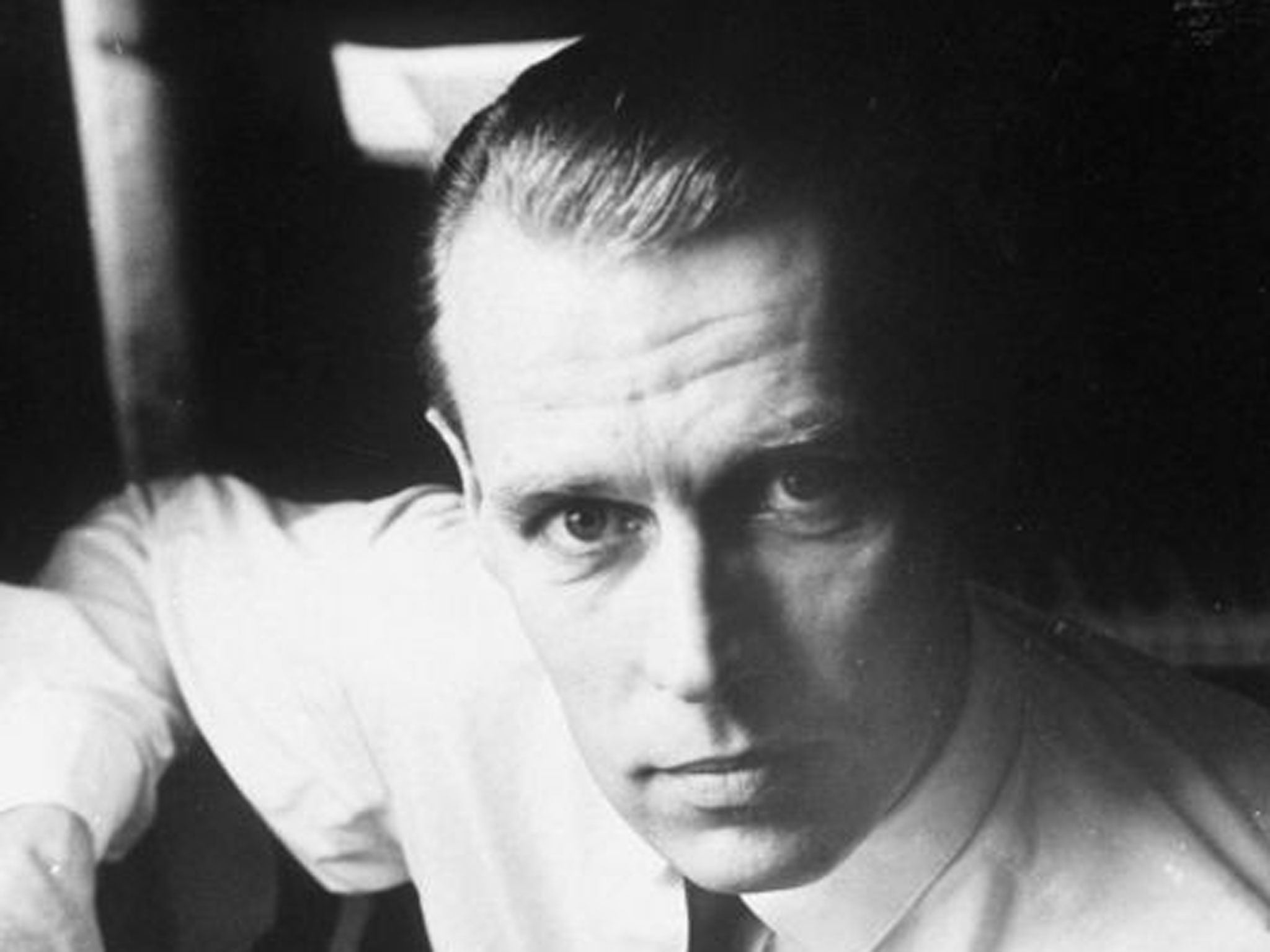

George Martin: Groundbreaking producer who oversaw The Beatles' best work and elevated art of album-making

Martin's work with The Beatles changed popular music forever but he was charmingly modest about his achievements

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As well as being the world's most respected and best-known record producer, George Martin redefined the role as a collaborative one. His work with The Beatles changed popular music forever – and even at the time, he was referred to as "the fifth Beatle".

He was charmingly modest about his achievements. "Whatever I did shouldn't be stressed too much," he said in 1974. "I was merely the bloke who interpreted their ideas. The fact that they couldn't read or write music and I could has absolutely nothing to do with it. Music isn't something which is written down on paper. Music is stuff you hear... I was purely an interpreter, rather like a Chinese interpreter at the League of Nations. But the genius was theirs, no doubt about that."

George Henry Martin was born in 1926 in Holloway, north London, the son of a carpenter. He started piano lessons when he was eight, only to have them cut short when his mother argued with the teacher. He continued on his own and became adept at learning by ear.

When he was 16, he ran a local dance band, The Four Tune Tellers, with his sister, Irene, as a vocalist. He served in the Fleet Air Arm during the war and when demobbed, he had the bearing of a military man. He deliberately lost his working-class accent.

He befriended a Wren, Sheena Chisholm, but his mother objected to their relationship. He married against her wishes in 1948. His mother died of a stroke three weeks later, and at the time he also had to cope with his wife's agoraphobia. They were married for nearly 20 years and had two children, Alexis (known as Bundy) and Gregory.

A professor at the Guildhall School of Music, Sidney Harrison, encouraged his talent and urged him to obtain a grant and study there. Upon graduation, he took up the oboe professionally, but needed regular income, and worked for a time in a dreary job at the BBC's music library. Harrison came to the rescue again, recommending him to Oscar Pruess, the head of Parlophone Records, one of EMI's in-house labels. Martin was appointed assistant recording manager in November 1950.

Martin discovered that Parlophone had an eclectic catalogue with a reasonable budget but no major performers. "We recorded artists like Jimmy Shand and we never talked about pop," he said. "All our releases were put into the categories classical, jazz, dance band and vocal."

Preuss retired in April 1955 and Martin became the youngest label manager in the UK. Preuss's secretary, Judy Lockhart-Smith, remained with him and, following an affair which led to his divorce, Martin married her in 1966. They had two children, Lucy and Giles.

Martin felt that there was a market for comedy – and in 1957, he produced Peter Sellers' parody of the skiffle craze, "Any Old Iron". It reached No 17 in the charts, and led to the albums The Best of Sellers (1959) and Songs for Swingin' Sellers (1960), which remain funny today. As Sellers felt that he could not parody Frank Sinatra adequately, Martin recruited a young singer to play Fred Flange on the latter album. Martin recognised his potential and, as Matt Monro, he recorded "Portrait of My Love" (1960) and "My Kind of Girl" (1961).

In 1960, Sellers and Sophia Loren capitalised on their successful film, The Millionairess, by having Martin produce a witty song about an Indian doctor and his patient, "Goodness Gracious Me". Bernard Cribbins performed some humorous takes on modern-day living ("The Hole in the Ground", "Right, Said Fred", "Gossip Calypso"), while Charlie Drake had a more frenzied approach ("Splish Splash", "Mr. Custer", "My Boomerang Won't Come Back"), all of which were hit singles.

There were few recording studios outside of London, so Martin would periodically take a mobile unit to Scotland to record Jimmy Shand and several other performers. He realised that the unit could be put to good use nearer to home if he recorded albums of West End successes. They included At the Drop of a Hat (1959) with the comedy songs of Flanders and Swann, and Beyond the Fringe (1961) with his first Fab Four, the iconoclastic satirists Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller. When television responded with That Was The Week That Was, Martin and the show's producer, Ned Sherrin, devised and recorded a special LP of their sharpest sketches.

Tangentially, Martin was intrigued by the BBC's radiophonic workshop, which came into its own with its sound effects for Doctor Who. Calling himself Ray Cathode, Martin made an exploratory single, "Time Beat" (1962). He recorded the highly eccentric and experimental group the Alberts, and allowed Rolf Harris to bring his Aboriginal instruments into the studio – all of which proved to be invaluable grounding for his work with the Beatles.

In 1961, Martin discovered The Temperance Seven (there were nine of them, which was thought funny at the time). Their deadpan versions of Twenties hits, "You're Driving Me Crazy" and "Pasadena", found their way into the Top 10, and the former was also Martin's first No 1 as a producer. The Temperance Seven were featured in the comedy film It's Trad, Dad! (1962), directed by Richard Lester, who would be behind the camera for the Beatles films A Hard Day's Night (1964) and Help! (1965).

From 1959 to 1962, Adam Faith became Parlophone's first consistent hit-maker, but the records were not produced by Martin. By May 1962, Faith's popularity had nose-dived and Martin wanted an act that could duplicate the success of Cliff Richard and the Shadows for another EMI label, Columbia. The Beatles' manager, Brian Epstein, had called at the HMV store in Oxford Street to have copies made of some tapes in their home recording service.

Martin recalled, "The engineer, Jim Foy, liked the sound and he rang me up on the fifth floor. I saw Brian and heard the tapes. Quite frankly, they weren't very impressive, but there was something peculiar about the way they sounded that I thought should be looked into. I asked Brian to bring them down from Liverpool so that I could have a look at them. I was immediately impressed by them as people, not particularly as musicians, but I did think that they sang in a very unusual and engaging style. I put them under contract knowing that I couldn't lose very much."

At that audition, Martin did not care for Pete Best's drumming and planned to replace him with a session musician.

Ringo Starr joined The Beatles and Martin released "Love Me Do" as a single with a lacklustre version of Mitch Murray's song "How Do You Do It?", being discarded. The Beatles thought "How Do You Do It?" was formulaic and Martin challenged them to come up with something better. They submitted "Please Please Me" and after the recording, Martin told them, "Gentlemen, you have just made your first No 1."

The Beatles took a free day from their tour with Helen Shapiro to make their debut album, Please Please Me. Much has been made of this, but four songs had previously been recorded – and it was standard practice to record four songs in a three-hour session.

Brian Epstein recommended Gerry and the Pacemakers for "How Do You Do It?", and together with "I Like It" and "You'll Never Walk Alone", they became the first act to hit the top of the charts with their first three records.

When Epstein returned from a trip to America, he gave Martin a copy of "Anyone Who Had a Heart" by Dionne Warwick. Martin thanked him and said that the song would be ideal for Shirley Bassey, whose 1963 hit "I (Who Have Nothing)" Martin had produced. Epstein insisted that he record it with his latest protégé, Cilla Black. Her version went to No 1 – and it led to the song's composers, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, writing "Alfie" for her. Bacharach played piano and wrote the arrangement, and Martin produced. The film of the event shows Bacharach insisting on take after take. "I think we got it that time," says Bacharach finally. "I think we got it on Take 2, Burt," replies Martin, laconically.

Another of Epstein's charges, Billy J Kramer with the Dakotas, had a string of hits, often with Lennon and McCartney songs. In one extraordinary year from April 1963 to April 1964, Martin's productions were at No 1 for 40 weeks.

He soon realised that The Beatles were something extraordinary. "The 'yeah, yeah, yeah' in 'She Loves You' was a curious singing chord. It was a major sixth with George Harrison doing the sixth and the other two the third and the fifth. It was the way Glenn Martin wrote for the saxophone." He chose the best musicians to supplement their sound, notably recruiting David Mason from the New Philharmonia Orchestra to play piccolo trumpet on "Penny Lane". Martin himself played an electric piano (which was speeded up) on "In My Life".

To begin with, Martin, his engineer (Norman "Hurricane" Smith, who became a hitmaker in his own right) and his tape operator (Geoff Emerick) tried to accurately reproduce how The Beatles would perform a song in a club, but that soon changed.

The Beatles had feedback on the start of "I Feel Fine", a sitar was brought in for "Norwegian Wood" and Paul was backed by a string quartet on "Yesterday". Simplistically, Martin realised Lennon's ideas and orchestrated McCartney's compositions.

Martin's role became more complex as more tracks became available, although even as late as 1968, he used only four-tracks for most of The White Album. He would experiment with different speeds, repeated loops and backward tapes.

In November 1966, "Strawberry Fields Forever" provided evidence of Martin's experimental intuition. They recorded the song in two different arrangements, in different keys and tempos. Lennon was not satisfied with either, and asked Martin to merge them. By changing the speed on the recorders, Martin combined the versions, culminating in what we hear today.

Martin had nearly left EMI at the start of 1962 as he believed he should be getting a cut of the royalties of successful records he produced. Even in 1965, he was only earning £3,000 a year – a decent salary, but minuscule compared to the millions of pounds his records were generating. Unable to persuade EMI, he established a team of independent producers, AIR (Associated Independent Recordings) with himself, John Burgess, Ron Richards and Peter Sullivan.

It was a gamble and EMI could have decided, out of spite, not to use them again. However, they still wanted Martin to produce The Beatles, but this time they would have to pay. Even so, the royalty rate that Martin negotiated was only one-fifth of one per cent.

Martin wrote the familiar "By George! It's the David Frost Theme" (1967) and his "Theme One" was an energetic composition for organ, brass and percussion for the opening of BBC Radio 1, also in 1967.

As Martin explained it, the watershed came in 1967. "It's very difficult for me to be impartial, but my personal favourite with The Beatles is Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. I do think that it is the best thing that they ever did. I suppose it was a producer's daydream. I was able to do everything that I've ever wanted to do and the boys were similarly anxious to make it a far-out thing for its time."

The Beatles returned from India in 1968 with many new songs. Martin tried to persuade them to make one great single album, but they insisted on a double album of 30 tracks, some of which he regarded as substandard. He subsequently discovered an ulterior motive: in order to negotiate a new contract, The Beatles were fulfilling their quota on the existing one.

In January 1969, and this time to honour a film contract, The Beatles allowed the cameras to capture them creating Let It Be. The album was intended to be totally honest, and Lennon told Martin that there was to be "no echoes, no overdubs and none of your jiggery-pokery". Martin approved of their aims, but the collapse of the friendships within the group created tension. There were great songs ("Let It Be", "Get Back") and a wonderful session on the roof of their Apple headquarters, but overall, it was disappointing.

The Beatles realised their mistake, and later in the year, they asked Martin to take control. The result was the mature-sounding Abbey Road, and the merging of song fragments into a symphonic suite on side two was Martin's idea. He said, "It proved to be a very happy album and I was very pleased that the group went out on a note of harmony and not one of discord."

While Lennon was working on the song "Instant Karma" with Phil Spector, he asked him if he could do anything with the tapes of the Let It Be sessions. Martin said, "John gave them to Phil Spector and asked him to overdub them, which was in direct contradiction of all he had said. He kept it very quiet and the first thing I knew about it was when the album came out. I was pretty annoyed, and so was Paul. The album credit reads 'produced by Phil Spector', but I wanted it changed to 'produced by George Martin, over-produced by Phil Spector'."

When The Beatles split up in 1970, both Lennon and Harrison preferred Spector for their solo recordings. McCartney recorded by himself, but returned to Martin in 1973 for the orchestral title song for the James Bond film Live and Let Die. He later produced McCartney's albums Tug of War (1982) and Pipes of Peace (1983).

Martin found that his hearing had been damaged as a result of working with The Beatles, but knew that he would not receive further commissions if this were widely known. For this reason, he grew his hair to cover his ears and accepted short-term work. His most durable relationship was with the soft-rock group America, and he produced their US hits "Tin Man" (1974) and "Sister Golden Hair" (1975).

Among his many one-off projects were the score for the Mickey Rooney film Pulp (1972), Tommy Steele's musical autobiography, My Life, My Song (1974), Jeff Beck's album Blow By Blow (1975) and Gary Brooker's No More Fear of Flying (1979).

Martin wrote his autobiography, All You Need Is Ears, in 1979 and a further volume, Playback – The Autobiography of George Martin, followed in 2002. The award-winning The Making of Sgt Pepper, a 1992 programme in The South Bank Show series, led to a book of the same name three years later, which Martin also developed into a stage presentation.

The first AIR Studios opened in Oxford Street in October 1970, the first client being Cilla Black. The studios were soon being used around the clock and the takeover of AIR studios by Chrysalis meant that Martin was a board member of several related companies, including the radio station Heart FM. A new AIR Studios in a converted church in Hampstead was opened in 1992. Martin also took a keen interest in the training of young musicians, notably at the Brit School in London and the Liverpool Institute of Performing Arts.

In the late 1970s, Martin drew up plans for a second studio complex in Montserrat. Many rock stars enjoyed working in this quiet, tropical paradise, but the island was devastated by Hurricane Hugo and a volcano in the early 1990s.

His later productions included a recording of Dylan Thomas's Under Milk Wood in 1988, with Anthony Hopkins reprising Richard Burton's role and a new score by Martin. In 1994, he worked with the harmonica player Larry Adler on The Glory of Gershwin, with several guest performers including Kate Bush, Cher and Sting. His farewell to the industry, In My Life (1998), featured celebrity performances of Beatles songs, including Sean Connery narrating the title song.

Martin's final production was Elton John's homage to Princess Diana, "Candle in the Wind '97", which became the biggest-selling record of all time. He undertook a considerable amount of fundraising for charities and he organised the unique Party at the Palace concert in 2002, which involved Brian May playing "God Save the Queen" from the roof of Buckingham Palace.

George Henry Martin, record producer and composer: born London 3 January 1926; CBE 1988, Kt 1996; married 1948 Sheena Chisholm (marriage dissolved; one daughter, one son), 1966 Judy Lockhart-Smith (one daughter, one son); died 8 March 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments