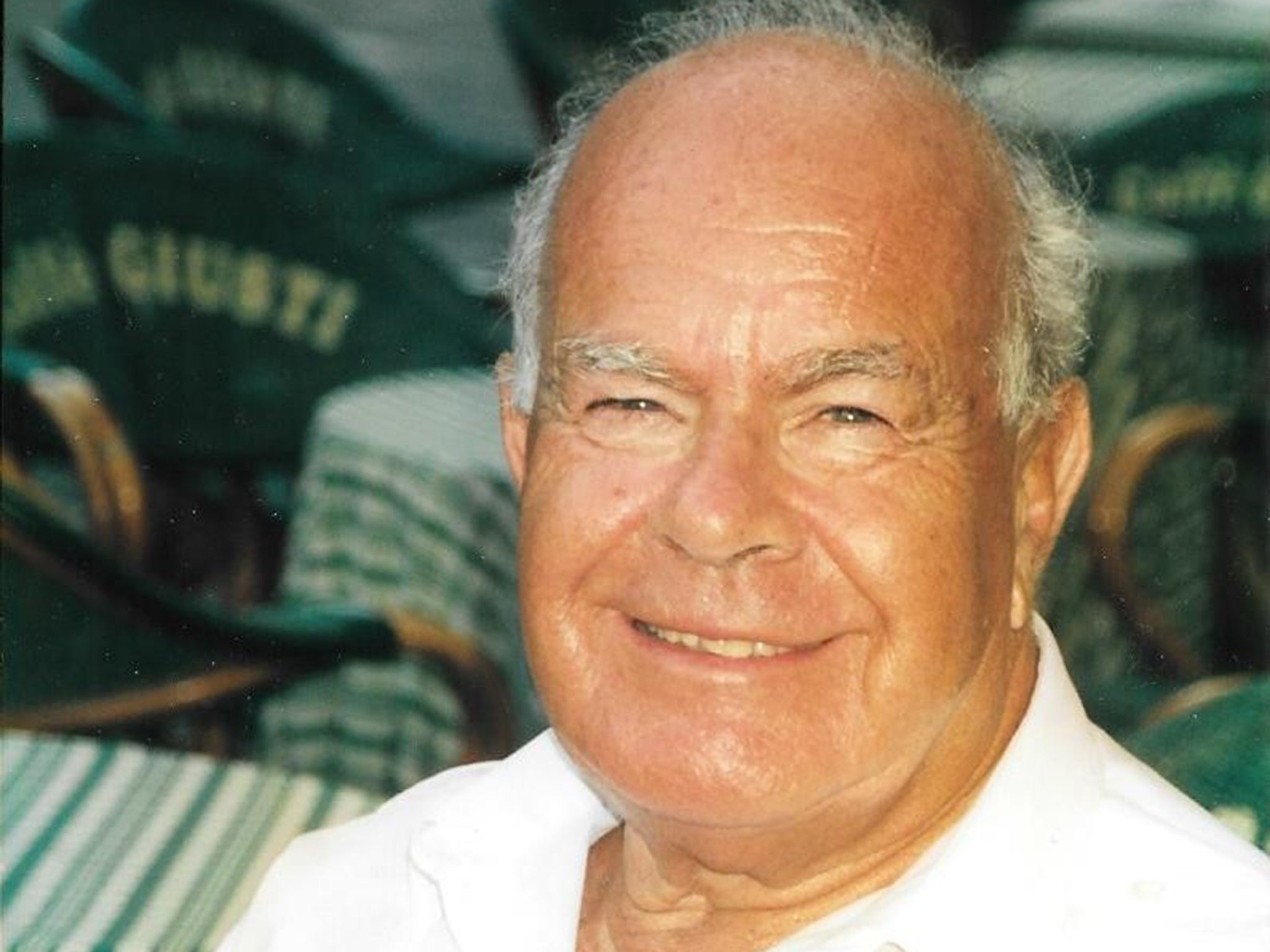

Geoffrey Perry: Soldier who captured Lord Haw-Haw by shooting him in the backside then forged a noted publishing empire

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Geoffrey Perry’s bullet made four neat holes in his quarry’s bottom, into each cheek and out again in turn, and with them a moment in history.

It was the come-uppance of Lord Haw-Haw, the sneering voice of menace from Hitler’s Reich that had enthralled British listeners throughout the Second World War.

For six years millions in bomb-hit cities and blacked-out countryside alike had defied official discouragement in order to tune in and hear the enemy broadcaster, real name William Joyce, bray: “Germany calling, Germany calling” before trumpeting Nazi propaganda in his distinctive haughty English tones.

Now, on 28 May 1945, the villain lay clutching his behind, and would soon know, like all of victorious England, that his captor was a man of the very race his hero Hitler had wanted to destroy – a Jew. The Jew, no less than Haw-Haw, who carried false documents, possessed an assumed name, and their chance meeting in a forest near Flensburg close to the Danish border would put it on everyone’s lips. For Perry, whose question, “You wouldn’t be William Joyce, would you?” had hit the spot, was himself, in truth, Horst Pinschewer, a Berlin-born boy who had been evacuated to England as the Nazi shadow loomed.

He had changed his name to “something pronounceable” when promoted Lieutenant in the British Army’s Pioneer Corps, which he had joined after his adopted country had, early in the war, interned him for some months as an enemy alien. Now, less than three weeks after the war’s end in Europe he was enforcing the Allies’ military occupation of the defeated Reich.

Perry and his comrade in Britain’s special-duties “T-Force” (“T” for “Target”), Captain Bertie Lickorish, had entered the forest, near a house they had occupied, in search of firewood for its stove. Joyce had gone there seeking calm after a quarrel with his wife, Margaret, the pair being under strain as they sought somewhere to flee to. Perry and Lickorish had paid the lost-looking fellow no attention; his mistake was to approach them and offer help, his voice immediately betraying him.

At the question, Joyce immediately thrust his hand down into his trouser pocket for papers made out in the fake name of “Wilhelm Hansen”. The movement made Perry fear a hidden gun, and fire his own. It happened to be a German one, a Walther pistol he had confiscated days earlier from a Hamburg policeman.

“Beaten to the draw!” crowed newspaper reports days later, and on a brief furlough home soon after Perry was asked for his autograph, the story having appeared, with pictures, worldwide. In fact Perry had at first feared he had made a dreadful mistake. “Suddenly I thought I was in a great deal of trouble,” he said later. “I had just wounded a German civilian... I had visions of being court-martialled.”

Only a few minutes later, when Lickorish had pulled out a second set of papers saying “William Joyce” were they sure this was their man, the American-born Fascist sympathiser raised in Ireland who while still holding a British passport had transferred his loyalty to Hitler. Joyce would be found guilty of high treason and hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 3 January 1946; Perry would go on to become a British publishing entrepreneur, prison visitor and Justice of the Peace.

Perry, whose parents had sent him to be educated at Buxton College, Derbyshire after Nazi restrictions on Jews in Germany became unbearable, had already briefly been the youngest staff photographer on the Daily Mirror, aged 17, just as war broke out, before his “enemy alien” status interrupted his advance.

His war included landing in Normandy in July 1944 a month after D-Day, seeing the decisive battle of the Falaise Pocket that August in which German forces sustained huge losses; and later in Lower Saxony, witnessing the opening up of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. With the Second Army Order of Battle unit, he also interrogated prisoners, his task being to find out from them what the enemy’s next military ploy might be in resisting the advancing Allies.

With T-force, once on German soil, he gained incomparable journalistic experience: he seized Radio Hamburg’s transmitter, acted as announcer at the microphone used hours before by Joyce for his last broadcast, and relaunched Hamburg’s newspapers. He took over virtually every paper in Germany’s northern region of Schleswig-Holstein, was one of the handful of Allied military personnel who set up Die Welt, the German national paper that still appears today, and began the German news agency DPD (Deutscher Presse-Dienst).

After the war, having left the Army in the rank of Major, he would use that experience to start, in 1948, his own company, Perry Press Productions. This ran house magazines for large industrial concerns, and was so successful that he was able to sell it to Thomson Publications, the group founded by the Canadian newspaper magnate Roy Thomson, in 1963. He became Thomson’s managing director of illustrated newspapers, then rose to be the company’s assistant managing director responsible for all its magazines. While at Thomson he set up Family Circle, the magazine that began the habit in Britain that was to catch on, of selling journals at supermarket check-outs.

After leaving Thomson in 1983 he set up a joint venture with Dutch and German publishers, introducing a version of Family Circle to Germany, then established and ran another company of his own, latterly with one of his two sons, retiring in 1992.

In 1952 he had married Helen Weissberger, the daughter of a comrade of his from the Pioneer Corps, and she was to be the model for the “ideal reader” Perry had in mind for his many magazines aimed at home-makers. Perry composed his memoir, When Life Becomes History, published in 2002, largely in tribute to her. She preserved all his wartime mementos, and shortly before her death in 2001 asked him to write it.

Horst Pinschewer (Geoffrey Howard Perry), soldier and publisher: born Berlin 11 April 1922; married 1952 Helen Weissberger (died 2001; two sons); died Elstree, Hertfordshire 14 September 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments