Gene Wilder obituary: Willy Wonka and Blazing Saddles star who grew to dislike the business of 'show'

'As a child I wanted to be loved for who I was,' he once said. 'When I was not, I settled for applause.'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

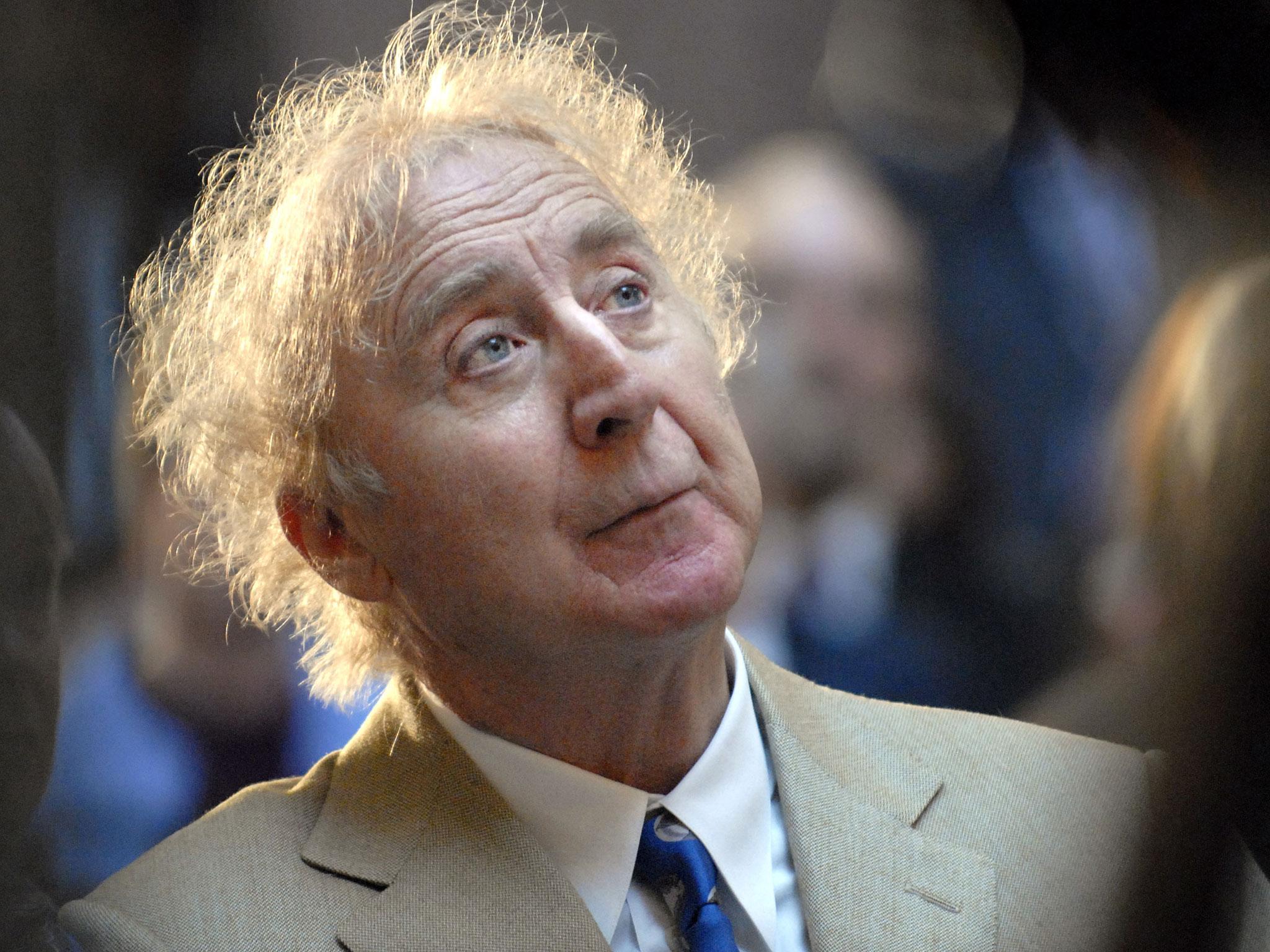

Your support makes all the difference.With his wide, quizzical eyes, his shock of curly hair and puckish features, Gene Wilder was a totally original comic actor, whose classical training lent his performances a sometimes disconcerting depth and whimsical irony.

He first attracted major attention with a memorable cameo in the film Bonnie and Clyde, after which he was cast as the naive and gullible accountant in Mel Brooks’ classic comedy The Producers. He went on to do some of his best work in further Brooks projects, including Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein, and later he scored a personal success on the London stage in Neil Simon’s comedy Laughter on the 23rd Floor. His private life in later years, though, was dogged by tragedy – his wife Gilda Radner died of cancer in 1989, and last year Wilder was himself diagnosed with lymphatic cancer.

The son of an immigrant Russian who had prospered from the manufacture of miniature liqueur bottles, he was born Jerry Silberman in 1933 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A bug-eyed and curly-topped child, he found his appearance caused chuckles and decided the best response was to be deliberately funny. “As a child I wanted to be loved for who I was. When I was not, I settled for applause.”

At the University of Iowa he attended drama classes, and upon graduation he travelled to England and enrolled at the Old Vic Theatre School in Bristol, where he won the school’s fencing championship. Returning to the United States, he taught fencing for a while, then worked as a chauffeur and toy salesman while studying at the Lee Strasberg Studio in New York. “My greatest dream came true when I was accepted from thousands of applicants into Lee Strasberg’s class at the Actors’ Studio. The so-called Method enabled me to arrive at an interpretation of a role through seeking equivalent emotions in my own experience. I use it all the time.”

While at the Studio, he decided on a change of name. “I picked Gene because of the hero of Thomas Wolfe’s novel Look Homeward Angel, and Wilder from Thornton Wilder whose Our Town was my favourite play.” He made his stage début off-Broadway in 1961, then played in several shows on Broadway, including Graham Greene’s The Complaisant Lover with Michael Redgrave and Googie Withers, and Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage with Anne Bancroft (who was later to marry Mel Brooks), before his breakthrough, when the director Arthur Penn cast him in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), his film début.

In that ground-breaking and much-acclaimed film, Wilder attracted favourable comment with his portrayal of the young man whose car is stolen by the outlaws and, after initially giving chase before thinking better of it, finds himself and his sweetheart pursued and forced to travel with the gang. Wilder’s look of stunned disbelief when his girlfriend inadvertently blurts out to Bonnie that she is 33 years old, and his queasy refusal of a half-eaten hamburger, were indications of his low-key comic style.

His next film, The Producers (1968), won him an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of the hyper-neurotic accountant cajoled by a wily producer (Zero Mostel) into deliberately producing a flop musical called Springtime for Hitler so that they can keep the over-subscribed investment money. Years later the actor, who spent several years in therapy, admitted, “I don’t think I could play that kind of character again. I’m probably too healthy emotionally. In those days I was afraid of my own shadow. I was afraid of life. When my life got straightened out, the parts changed.”

Wilder gave one of his funniest screen performances in Bud Yorkin’s Start The Revolution Without Me (1970), a frequently hilarious farce on the twins-switched-at-birth theme and the first of several pastiche films made by Wilder, who had loved movies since his childhood and delighted in parodying the various genres. In Brooks’ Blazing Saddles (1974), every cliché of the western was mercilessly lampooned, and in Young Frankenstein (1974), developed by Brooks and Wilder from an idea by Wilder, it was the monster-horror genre, with its highlight a song-and-dance rendition of “Puttin’ on the Ritz” performed by Frankenstein (Wilder) and his creation (Peter Boyle).

Taking inspiration from his mentor Brooks, Wilder himself wrote and directed a pastiche of detective movies, The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother (1975), with Wilder also playing the lead as the manically jealous sibling who is determined to outdo his famous brother in everything, from fencing and inventing to fiendishly clever detection. (Other Brooks alumni Madeline Kahn and Dom DeLuise were among his co-stars in this enormously popular spoof.) Wilder’s quirky personality also found apt outlets in Mel Stuart’s musical version of Roald Dahl’s children’s book Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971) as the enigmatic and wickedly mischievous factory-owner, and Woody Allen’s Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About Sex But Were Afraid To Ask (1972).

In the latter, Wilder starred in the episode most people recall best, as a mild-manned doctor who falls hopelessly in love with an Armenian sheep named Daisy. It was a quintessential Wilder role. “I suppose what I liked to do, from a young age, was something bizarre and play it straight.” He added, “The thing you ought to know about sheep is that when there’s a loud noise you’re going to get about 50 to 100 pellets dropped. And I was in bed with a sheep. Luckily, they had someone there with a vacuum cleaner to suck up all the pellets.”

In Stanley Donen’s surprisingly ineffectual musical version of Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s classic children’s tale The Little Prince (1974), about an aviator who crashes in the desert and encounters a little boy from another planet, Wilder was the wily fox who tries to lure the child into danger with the Alan Jay Lerner-Frederick Loewe song “Closer and Closer”. Wrote Lerner bitterly later, “The director took it upon himself to change every tempo, delete musical phrases at will and distort the intention of every song, until the score was entirely unrecognisable.” The same year Wilder was reunited with Zero Mostel in an updated and misconceived film of Ionesco’s Rhinocéros.

He teamed up for the first time with the former night-club comic Richard Pryor (who had been one of the writers of Blazing Saddles) in Arthur Hiller’s Silver Streak (1976), an enjoyable comedy-thriller deliberately conceived in Hitchcock style by writer Colin Higgins, in which exhausted businessman Wilder finds mystery and murder on a cross-country train he has boarded hoping for relaxation. Wilder and Pryor complemented each other beautifully and were to make several more films together.

Wilder took creative control of his next venture, when he wrote, produced, directed and starred in a tribute to Chaplin, The World’s Greatest Lover (1977), playing Rudi Valentine, a baker in mid-Twenties Milwaukee whose ambition is to be recognised as the greatest lover alive. Sidney Poitier’s raucous prison comedy Stir Crazy (1980) was uneven, but it reunited Wilder with Pryor and their teamwork was frequently a joy. The film took over $100m at the box-office and Hanky Panky (1982) was planned as a sequel, but Pryor’s part was re-written for the comedienne Gilda Radner, with whom Wilder had fallen in love.

The couple were married in 1984, the year the pair starred in Wilder’s adaptation of the French hit Pardon Mon Affaire. Re-titled The Woman in Red and starring Wilder (who also directed) as a mild, happily married man who becomes obsessed with a gorgeous young woman (Kelly LeBrock), it was considered inferior to the sparkling French original, but did very well at the box-office. Wilder then conceived an old-dark house comedy-mystery as a vehicle for himself and Radner, but the result, Haunted Honeymoon (1986) sadly misfired. In 1989, after a long battle with ovarian cancer, Radner died.

Wilder had been married twice earlier, to the playwright Mary Mercier and to Mary Joan Schutz, but would never discuss these earlier failed marriages. “He avoids interviews like the plague,” said a friend. Having been absent from the screen for some time, he returned after Radner’s death to make two more comedies with Pryor, See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989), in which they were a deaf man and a blind man who witness a murder for which they become prime suspects (Kevin Spacey played one of the villains) and Another You (1991), with Wilder as a psychotic liar put into the care of a street hustler (Pryor) performing community service. Both films had critics lamenting the fact that the team’s material was unworthy of their talents, and although the first made a small profit, Another You quickly disappeared.

In 1996 Wilder travelled to London to appear in a stage production of Neil Simon’s comedy Laughter on the 23rd Floor. Based on Simon’s youthful experience working on the Sid Caesar television show (with Wilder’s role a thinly disguised Caesar) it had been only a modest success on Broadway and fared similarly in London, though it was generally agreed that Wilder was better casting in the leading role than the more manic Nathan Lane had been on Broadway.

The critic Clive Hirschhorn wrote in the magazine Applause, “Wilder’s angst-ridden persona, his pained, neurotic body language, mesmerised deadpan stare and ‘clenched hair’ (to quote Neil Simon) are perfect...You care about this loveable, infuriating eccentric and, as a consequence, about the people around him.”

“I wasn’t sure I was right for the part,” Wilder told the interviewer Ronald Bergan, “so I called Mel. He said that on Broadway they had missed something essential about Caesar. ‘They didn’t understand that Sid was a shy man like you. When he was performing he could be a giant, but otherwise he was painfully shy.’ I realised then why they wanted me, because I am all emotion. Everyone else is wisecracking, but I’m funny, not because of jokes, but because my behaviour is so crazy.”

During the last decade and more, since the death of Radner, Wilder worked hard to raise awareness of ovarian cancer, spearheading a public campaign and helping to establish a support group, Gilda’s Club. “Since Gilda’s death,” said a friend, “he has been a real health nut.” But in 1998 he told People magazine, “I don’t want to talk about cancer any more.” Later it emerged that he was undergoing treatment for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Among those to offer comfort was his fourth wife Karen Webb, a speech pathologist, whom he married in 1991, and friends such as actor Mandy Patinkin, who commented, “Attitude is everything, and Gene has the gift of laughter.” Wilder was said to be in complete remission in 2005.

Even before he became ill Wilder had slowed down on the performing front - although he won an Emmy award for an appearance in comedy series Will & Grace. “I don’t like show business, I realized,” he said in 2008. “I like show, but I don’t like the business.” But Wilder would later turn his hand to books. In 2005 Wilder produced a memoir, Kiss Me Like a Stranger: My Search for Love and Art; a collection of stories, What Is This Thing Called Love? (2010); and three novels: My French Whore (2007), The Woman Who Wouldn’t (2008) and Something to Remember You By (2013).

Wilder died at his home in Stamford, Connecticut, from complications of Alzheimer's disease, according to his family. Wilder's nephew, Jordan Walker-Pearlman, said the actor had chosen to keep his illness secret so that children who knew him as Willy Wonka would not equate the whimsical character with an adult disease.

Gene Wilder, born 11 June 1933; died 30 August 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments