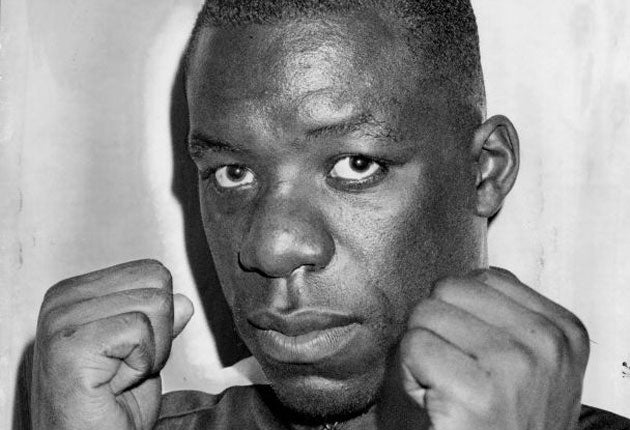

Gary Mason: Former British heavyweight boxing champion

There was a moment of raw drama in the seconds between rounds six and seven of Gary Mason's last proper fight as a professional boxer in Wembley's grand and stained ring in March 1991.

Mason was the defending British heavyweight champion and after six rounds two judges had him level. The referee, a kindly ex-amateur star called Larry O'Connell, had Mason in front by a slender margin. However, Mason's left eyebrow was cut and bleeding and his right eye was totally lost under a grotesque swelling; more disturbingly, his young opponent, Lennox Lewis, was hitting him at will. Twelve months earlier, Mason had undergone surgery on his right retina, an eye that was no longer even visible. "The pain was unbelievable," Mason said.

O'Connell traipsed to the corner, peered anxiously over the shoulders of the men desperately working on Mason's wounds, and was clearly intent on stopping what was slowly becoming too painful to watch. Instead, Mason's cutsman and good friend Dennie Mancini mouthed: "Don't, it's his living." O'Connell, with his head a little lower, backed away, but had no alternative 44 seconds later when he finally rescued Mason from the fists of Lewis. It was, as the great British boxing writer Harry Mullan wrote, "pure blind courage" that kept Mason going.

Mason entered the ring that night unbeaten in 35 fights, ranked No 4 in the world and as the slight betting favourite. He exited the orchestrated savagery facing an uncertain future, with no chance of ever being allowed to box again in Britain with his damaged eye. Lewis fought on, became the undisputed world heavyweight champion, the best fighter of his generation and a relaxed family man with $100m safely stashed. Three years later, Mason somehow acquired an American licence and knocked out two bums before finally quitting the ring in 1994 when he was correctly refused a British licence. "I made peanuts for those two fights. Rubbish money," Mason said.

There are wins on Mason's record that prove he was a massively underestimated British heavyweight, but the damaged retina, sustained in a March 1990 fight, finally ruined a proposed Mike Tyson fight and eventually, after the Lewis loss, forced Mason to retire having lost just once in 38 fights. Perhaps his best win was against the 1984 Olympic champion Tyrell Biggs in 1989; a win that moved him close to a Tyson fight.

The Tyson fight never happened and Mason never really had the same profile as Frank Bruno. He was known as "the other British heavyweight" for so long and toiled in Bruno's shadow – and sparred with his great neutral nemesis for years. Mason always maintained that it was Bruno's fists, during sparring, that damaged his eye, a simple declaration without malice from a man with few, if any enemies. His smile and deafening laugh eased all situations, even on the streets of Battersea, Wandsworth and Clapham where he grew up after leaving Jamaica as a baby.

"Me and Frank have very different aims. He wants to be the world champion and I just want the money!" Mason said.

Away from boxing, Mason ran a jewellery store called Punch 'n' Jewellery, made an attempt at promoting boxing in which he pushed himself as the British Don King, and embarked on an arm-wrestling adventure that was briefly screened. "Honest, it's the greatest sport in the world," Mason said.

He played three professional games of rugby league for the London Broncos, scoring a try in his first match, but there were dull stints as a security guard in a hospital and too many anonymous years driving a taxi. He also tried his hand in the music business with a white rapper. "Buncey, trust me. He's Stockwell's Eminem," Mason implored me at the time.

He also briefly had a prominent position at Sky as part of their fledgling and entertaining boxing team in the early Nineties. Sadly, what he thought was an off-air rant about a fellow presenter's garish tie ended with his sacking, and no doubt the first of countless visits to the job centre. "I wait in line and I still have to sign autographs at the job centre," said Mason.

In September 1991 Mason arrived at St. Barts Hospital late one night to meet with stricken boxer Michael Watson's mother, Joan, who was staying in a tiny room next to the intensive care unit. A week earlier, over 17 million people had watched on ITV as Watson collapsed in the 12th round of a fight against Chris Eubank. A few weeks before the fight, Mason, who had been forced to retire six months earlier, had been given £10,000 after a benefit evening at the Circus Tavern. Mason was never a wealthy man.

He sat with Mrs. Watson, prayed with her and then visited Michael, who had boxed on the same night when Mason made his debut in 1984. Mason cried as he stood over Watson's still body in the eerie glow of the intensive care unit. They had been friends for a long time. When Mason left Barts that night, long after midnight, he was £10,000 pounds lighter. "Michael's family needs it more than me," he said. He refused every effort by me to make the donation public.

Just over a year ago I bumped into Mason in Shepherd's Bush one morning and invited him to be a guest on my BBC London show. He agreed; we talked about his heavyweight days, fights at Battersea Town Hall and the lack of depth and excess of cash in the division now. He just laughed that great big booming Mason laugh and smiled.

"I don't regret a thing or envy anybody," Mason told me. "Nobody said it was going to be easy."

Gary Mason, boxer: born Jamaica 15 December 1962; died London 6 January 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies