Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Francis Golding was one of the country's leading architectural, planning and conservation consultants, and had a big influence on the look of contemporary London. He died from injuries sustained in one of the cycling accidents that occurred in Central London on 5 November. Golding's major clients included Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Terry Farrell, Rick Mather, Rafael Viñoli, Jean Nouvel and Michael Hopkins. With Foster he worked on the "Gherkin"; with Nouvel on One New Change, also in the City of London; and with Rogers he consulted on the controversial Chelsea Barracks. He was cross about the Prince of Wales's intervention, though in the case of the Prince's Poundbury development in Dorset, he said, "I've seen the past and it works."

He was born in Macclesfield in 1944, where he attended grammar school. His father, who fought in the First World War, had a private income and only took to repairing vintage cars after some poor investments following the Second World War. His mother cooked school meals until almost the end of her life. Francis went up to Clare College, Cambridge with an Exhibition in 1962 to read English (under FR Leavis) and Fine Arts, taking his degree in 1966. He sat the Civil Service exams and in 1967 joined the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works (which was absorbed into the Department of the Environment in 1970).

From 1975-77 he savoured being attached to the Royal Commission on the Press. The next year he became Assistant Secretary at the DoE, and was particularly proud of his role in the creation of the 1977 Rent Act. In 1984 he joined English Heritage as Head of Secretariat, where he worked closely with Lord Montagu of Beaulieu. Subsequently he was Head of Properties at English Heritage from 1986-90.

The summer of 1981 saw the worst urban riots of the 20th century and Golding was in charge of the Urban Programme, the effort to save Britain's inner cities. Friends remember him being impressed by Michael Heseltine's honourable behaviour, visiting Liverpool almost every week. The release of Cabinet Papers in 2011 revealed that Heseltine, in a paper called It Took a Riot, had demanded £100m a year of new money for Liverpool alone, a measure other members of the Thatcher cabinet defeated.

Golding's career acquired a wider focus in 1992 when he became Secretary of the International Committee on Monuments and Sites, until 1994. He delivered a paper to the 10th General Assembly in Sri Lanka in 1993 entitled State Intervention for Conservation in a Mixed Economy Policy and Practice in the United Kingdom, presenting his thoughtful, balanced approach to conservation: "The British system of protecting historic buildings and sites has grown and developed in complexity for a hundred years. Individually its separate components make sense in policy terms. Viewed collectively from an economic point of view, they present many paradoxical consequences, especially when their secondary effects are considered. Anyone thinking of adopting them as a model would do well to keep this in mind."

From 1995-99 Golding was Secretary of the Fine Art Commission (succeeded by the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, with Golding as its executive chairman) – the government's adviser on architecture, design and urban space in England, presided over by Lord St John of Fawsley. In 1998 The Independent presented Golding's "robust" defence of the Commission against the charge of cronyism, insisting that "three of the last four plans Sir Michael Hopkins has brought here have been roundly condemned … and Richard Rogers completely redesigned an office in Soho after comments from the Commission." The writer of the piece, James Fisher, continued: "Sitting in his august office beneath a painting by Howard Hodgkin [a friend], Golding also swiftly dismisses the idea that the Commission is partial to a particular architecturalism – modernism, classicism, post modernism. 'Buildings have to be appropriate to their place,' Golding said, 'and that has nothing to do with style and everything to do with quality.'"

The nature of the work meant that controversy was always near at hand. In January 2000 David Taylor reported in the Architectural Journal that just before Christmas the Architects' Registration Board had "descended into farce… when four enraged architect members of the board resigned in protest at … a remarkable U-turn [when it] dropped its preferred candidate [for chief executive], Francis Golding." In 3 February the AJ quoted Francis saying, "My whole career has been about writing things down in a clear way." The writer further remarked, "Those who have worked with him admire his 'nose for bad projects' and his 'fair-mindedness'."

In a speech for the Melvin Debates at the Royal Institute of British Architects in 2011 entitled "The Architectural Uneasy," Golding said: "On the whole I go to enormous lengths to tell clients not to change their architects but to get better work out of the architects they have chosen."

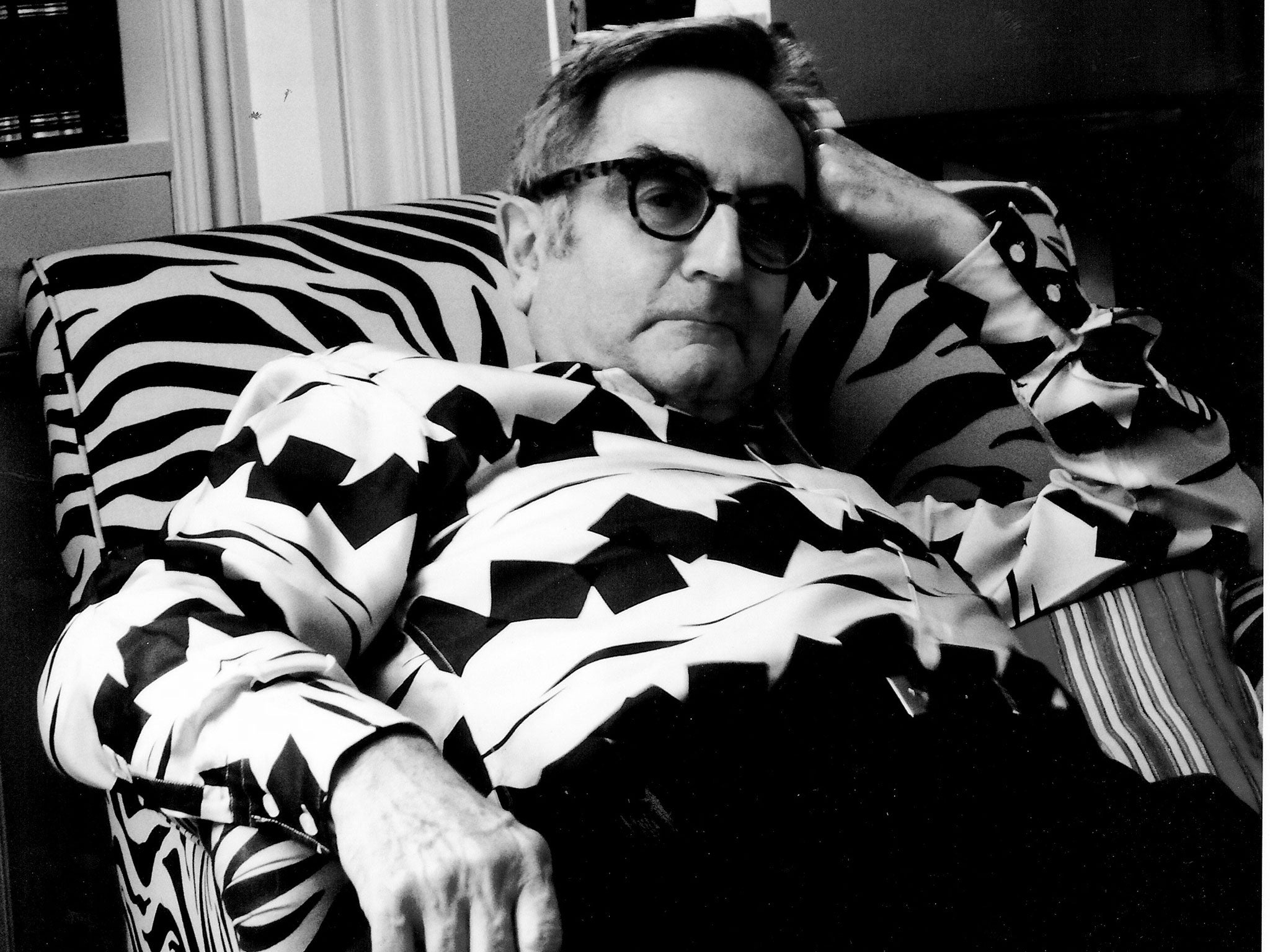

In 2002, he published Building in Context, a book of which he was justifiably proud. Laconic, with a bone-dry sense of humour much relished by his friends, Francis dressed elegantly, even flamboyantly. He was a connoisseur of Chinese jade and pots, of which he had an exquisite collection, while his other recreation in Who's Who was "visiting India". He had lived in a beautifully appointed 1823 house in Islington for the last 30 years with his civil partner since 2006, Satish Padiyar, an art historian at the Courtauld Institute. There they entertained, with Francis cooking imaginative, delicious food for their wide and remarkable social circle that included artists, collectors – and even a few architects.

Francis Nelson Golding, architectural, planning and conservation consultant: born Macclesfield 28 January 1944; Honorary Fellow, RIBA 2000; civil partner 2006 Dr Satish Padiyar; died London 7 November 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments