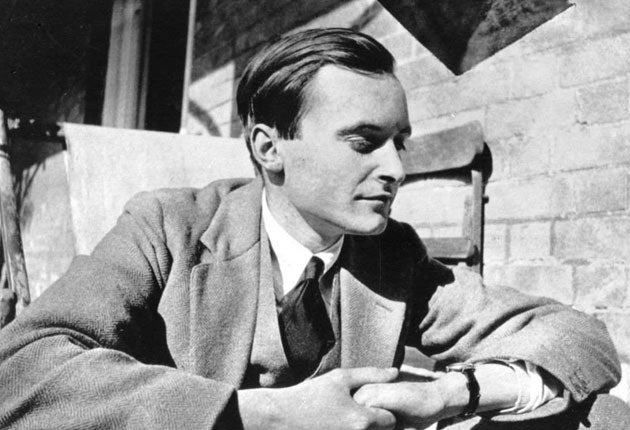

Edward Upward: Writer of politically charged novels and short stories who was a contemporary of W.H. Auden

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The death of Edward Upward at the age of 105 breaks the final link with that extraordinary group of left-wing writers who dominated English literature in the 1930s.

The literary editor John Lehmann recalled that in 1932 he had "heard with the tremor of excitement that an entomologist feels at the news of an unknown butterfly, that behind Auden and Spender and Isherwood stood the even more legendary figure of an unknown writer, Edward Upward". Upward had not at this stage actually published a book, and never attracted a wide readership, but he was in effect the fourth man behind that famous 1930s triumvirate.

By far the most politically committed of the group, he joined the Communist Party at Bethnal Green in 1934 and did not leave it until 1948. Stephen Spender recalled that it was after discussing the uncertain political future with Upward in Berlin in the early 1930s that his "vaguely distressed consciousness began to formulate itself along lines laid down by Marxist arguments". Auden, too, was influenced both by Upward's politics and his writing: The Orators in particular owes a great deal to Upward's imaginative landscape.

It was Christopher Isherwood, however, who was closest to Upward, having first met him at school and then followed him to university. "Never in my life have I been so strongly and immediately attracted to any personality, before or since," Isherwood wrote in 1938. "He was a natural anarchist, a born romantic revolutionary." As undergraduates, Isherwood and Upward invented a surrealist-gothic English village called Mortmere, about which they wrote fantastical and cheerfully obscene stories, featuring coprophagy, necrophile brothels and the like. The most accomplished of these, Upward's "The Railway Accident", was eventually published (bowdlerised, pseudonymously and in America) in 1949. Throughout their lives the two writers always showed each other work in progress, and Upward, Isherwood wrote, remained "the judge before whom all my work must stand trial and from whose verdict there is no appeal".

In describing "The Railway Accident" as "a nightmare about the English", Isherwood might have been speaking for all Upward's work, in which paranoia, dreams and hallucinations frequently feature. Upward's most significant achievement was The Spiral Ascent (1962-1977), an autobiographical trilogy of novels about a poet and schoolmaster, Alan Sebrill, trying to reconcile his literary ambitions with his political beliefs. It is undoubtedly the most comprehensive account we have of middle-class involvement in the Communist Party of Great Britain, and is therefore an important historical document. Arguments over its literary merit persist: several commentators who ought to know better have dismissed it as unreadable, which only makes one suspect that they haven't really tried. Although the narrative occasionally gets bogged down in Marxist dialectic, the trilogy is hugely rewarding to read, and is shot through with genuine lyricism and high comedy.

The son of a doctor, Edward Falaise Upward was born in Romford, Essex, in 1903. He was educated at Repton School, Derbyshire and obtained a scholarship to read history at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. His initial ambition was to be a poet and his "Buddha" was awarded the Chancellor's Medal for English Verse in 1924. It says much for his natural diffidence that he stopped writing poetry after showing some to Auden. "He said it was no good and that was it," he recalled.

He never found writing easy and after graduating spent several years trying unsuccessfully to complete a novel set in a golf club. He did however publish some fine stories in influential magazines of the 1930s.

A brief and unenjoyable spell as a private tutor provided Upward with the background for his first novel, Journey to the Border (1938). By the time it was published, Upward was an active member of the Communist Party and had contributed a grimly doctrinaire "Sketch for a Marxist Interpretation of Literature" to Cecil Day Lewis's symposium The Mind in Chains. In it, Upward proclaimed with all the zeal of a recent convert that unless a writer "has in his everyday life taken the side of the workers, he cannot, no matter how talented he might be, write a good book".

Upward, fortunately, had written a good book, in which a disaffected young tutor is driven to the brink of insanity by his job but eventually saved by joining a local workers' movement. The descriptions of the tutor's employers and of the hallucinations the young man suffers allowed Upward's considerable satirical and visionary gifts free range, while the ending advocated serious political commitment.

By now Upward had become a full-time teacher and, after working in some highly eccentric private schools, joined the English department of Alleyn's School, Dulwich, where he remained for twenty-nine years, retiring to Sandown on the Isle of Wight in 1962. He had married Hilda Percival, a teacher and a fellow-member of the Party, in 1936, and they had a son, Christopher (named after Isherwood, who was appointed 'Marxfather'), and a daughter, Kathy (named after an early literary idol, Katherine Mansfield).

After the war, the Upwards felt that the Party was straying from its Marxist-Leninist roots and becoming unacceptably revisionist, and when they were hauled up before a committee to explain why they had publicly criticised Harry Pollitt's Looking Ahead, Hilda tore up her Party card.

Leaving the Communist Party proved very traumatic for Upward, particularly since he was trying to write a novel about his political experiences. He fell prey to a number of psychosomatic illnesses and eventually suffered a breakdown. All of this is described in The Spiral Ascent, in which Upward, like Isherwood, treated autobiographical fact with the freedom of fiction.

It was not until 1962, however, that the first volume of the trilogy, In the Thirties, finally appeared in print. It proved difficult to publish such a book in the Cold War period: Leonard Woolf suggested that Upward should remove the communist element – which would have left him with a very slim volume indeed. Heinemann eventually agreed to publish the novel and its sequel, The Rotten Elements (1969), but refused the final volume, No Home but the Struggle, on financial grounds, until lobbying by Upward's admirers and the offer of an Arts Council grant persuaded them to publish it along with its predecessors in an omnibus volume (1977).

Once the trilogy was complete, Upward appeared to fall silent again, although occasional stories appeared in Alan Ross's London Magazine and elsewhere, and were collected in The Night Walk and Other Stories (1987). By the time Upward celebrated his 90th birthday in 1993, none of his work was in print; yet a profile published in the Independent magazine to mark the occasion attracted the attention of Stephen Stuart-Smith of the Enitharmon Press, who subsequently oversaw an extraordinary late flowering.

The surviving Mortmere stories, a revised version of Journey to the Border, and a new volume of stories appeared in 1994. Two further volumes of short stories followed, along with two beautifully produced pamphlets. This revival culminated in an extensive bibliography of Upward's work (2000) and a selected volume of his short stories, A Renegade in Springtime (2003), both edited by Alan Walker.

In September 2003, friends and family gathered in Sandown to celebrate his 100th birthday. In 2005, shortly before his 102nd birthday, he became the oldest ever writer to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and was awarded the Society's Benson Medal. He left all of his papers, including his diaries, to the British Library.

Edward Falaise Upward, writer and teacher: born Romford, Essex 9 September 1903; married 1936 Hilda Percival (1 son, 1 daughter; died 1995); died Pontefract, Yorkshire 13 February 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments