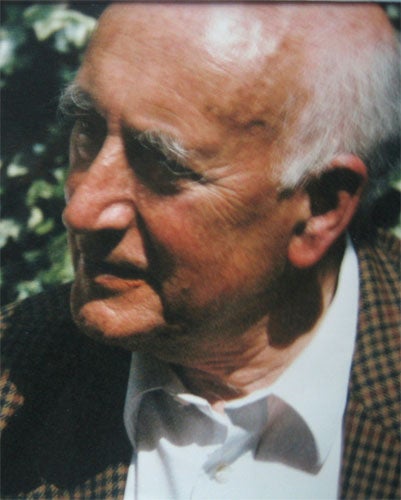

Dr Arthur Williams: Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst noted for his work with offenders

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Arthur Williams was a noted psychiatrist and psychoanalyst whose pioneering work with offenders, including murderers, influenced generations of forensic clinicians.

Born in Birkenhead during the onset of the First World War, he spent his childhood on the Wirral, where he developed a passionate love of nature. At the age of 13 he visited Liverpool Museum, where he discovered its large collection of butterflies, and was encouraged in his interests by the museum. This inspired him to want to train as a zoologist. Later, he felt torn between this wish and a calling to medicine.

A scholarship to study medicine settled the matter. From medicine he went on to train in psychiatry, and then at the Institute of Psychoanalysis in London. He was Melanie Klein's last patient before her death. His original inspiration to study psychoanalysis was Jonathan Hanaghan, Dublin's first psychoanalyst, who had earlier lived on Merseyside and who held evening discussions on the subject at his house, which the young Williams attended. There, an inner course was set that led to a career that spanned 60 years of exploration of the disturbed mind. Williams influenced a great many clinicians and psychotherapists working with pre-psychotic and highly disturbed adolescents, in addition to his work in the forensic clinical field.

He was a distinguished chairman of the Adolescent Dept at the Tavistock Clinic in London in the early years of its existence. A typical phrase that he used to describe the predicament of many failing adolescents who came to the clinic was that they were in thrall to the "false gods of drugs, drink and delinquency", which he considered could be used to evade necessary psychic pain at the cost of psychological development. Professor Christopher Cordess recalls inviting him to undertake specialist consultation to an adolescent forensic case conference at the Maudsley Hospital. It was a remarkable meeting because the chairman, out of courtesy, asked Williams to give his opinion first: such was the profundity, sympathy and clarity of Williams' Kleinian-influenced formulation that the senior Maudsley clinicians present had little of interest to add. This enormously impressed the trainees, of whom Cordess himself was one. Later, Williams and Cordess were to co-author a highly influential article entitled The Criminal Act and Acting Out in Forensic Psychotherapy – Crime, Psychotherapy and the Offender Patient.

Many trainees in supervision with Williams came to appreciate his emotional warmth, generosity and professional modesty. His pioneering treatment of men detained in HMP Wormwood Scrubs, where he worked over a number of years, achieved remarkable results. He developed a special method of analysis and reconstruction of the homicidal act: in particular, for the explosive, sudden, catastrophic type of homicide in which the arousal at the time of the killing frequently produced amnesia for the circumstances of the event and its precursors. His aim was to help the individuals face the reality of what they had done to enable them to have a more genuine remorse and an understanding of the enormity and irreversibility of killing. He was aware that they could never make full reparation for their act of killing and that this truth, when it came home to them, could precipitate a risk of suicide or overwhelming depression. For Williams, helping these lost individuals manage their guilt and anxiety was a great deal more creative than punishment or preaching.

His innovative theoretical model included both historical theories of memory recovery based on the early work of Freud and the psychologist Pierre Janet, and anticipated some of the recent developments on traumatic stress, including amnesia of shocking events as an unconscious avoidance mechanism. He used Klein's theories of psychotic mental mechanisms to help his patients incorporate undesirable and repudiated aspects of themselves as part of the recovery process. He advanced the view that catastrophic homicide was often dependent on a final significant event that short-circuited a constellation of traumatic experiences so that an otherwise successful defensive organisation within the individual became overwhelmed and then collapsed. These ideas are reflected in the work from Broadmoor on the "over-controlled personality" and Williams wrote many influential articles. His papers were collected together in the book Cruelty, Violence and Murder, which I had the good fortune to work on with him.

Williams was an active participant, along with Leo Abse, on a committee working towards the abolition of the death penalty. He firmly believed, on the basis of his clinical experience, that even the most hardened criminals were not beyond repair. Williams chaired the London Clinic of Psychoanalysis, a unique low-fee psychoanalytic treatment service, which continues to this day. He was widely admired for his freedom of thought and lack of subservience to any particular theoretical doctrine.

Less well-known was the delicacy and insight of his writing on his beloved poets – especially Keats and Coleridge. For now this is sadly only available in French, but his short articles attest to a depth of insight and knowledge of great poetry which, alongside the beauties of his successive gardens, must have sustained him through his darker areas of thought. He will be remembered above all for his gift of friendship across generations, the ever-present twinkle in his eye and his lovely, ready sense of humour.

Professor Paul Williams

Arthur Hyatt Williams, psychiatrist: born Birkenhead 23 September 1914; married 1939 Lorna Bunting (deceased, four sons), 1972 Shiona Tabor née White (deceased, two stepdaughters), 1987 Gianna Henry née Polacco (two stepdaughters); died Cheltenham 27 August 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments