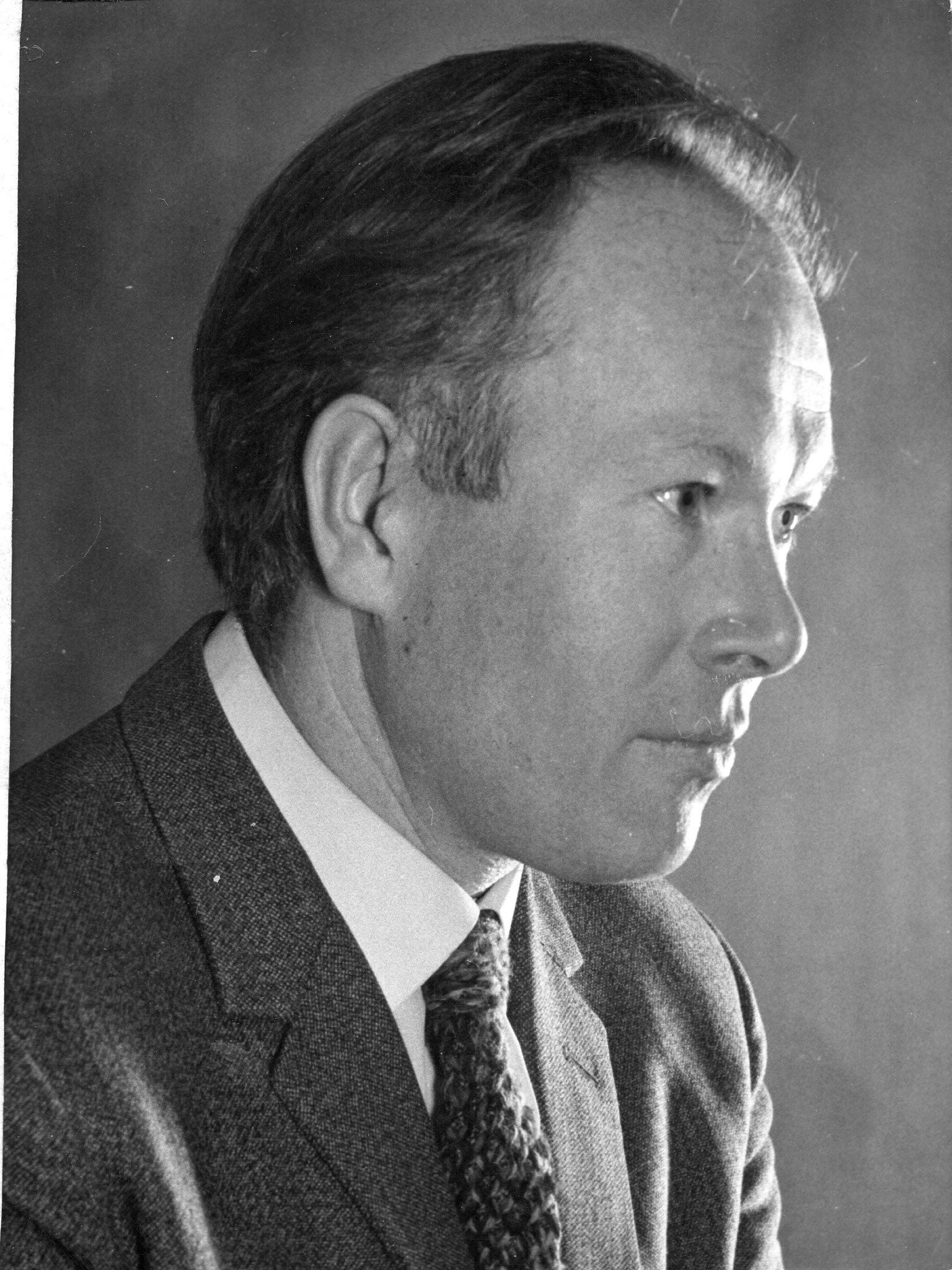

Doctor Jim Birley: Pioneer of local care who also changed the way we view schizophrenia

Jim Birley was one of the most distinguished figures in British psychiatry, whose eminence and humanity brought discernible benefits to the global psychiatric scene. He combined an acute brain with a towering moral sense, a lack of pretension and an irresistible sense of fun. With Birley, the kindest, most generous-spirited of men, the joke was never far away.

Born in 1928 near Harley Street to a neurologist father famed for his work on fatigue in First World War pilots, Birley moved to his grandparents' house in Essex after his father died. He was educated at Winchester College, where he was head boy, and at University College, Oxford. He became interested in psychiatry while working as a (conscript) Junior Medical Specialist in the army in Germany. He returned to the UK and after further medical experience spent a year working with the controversial Dr William Sargant before taking a clinical position in 1960 at the Maudsley Hospital. He was to remain there for the remainder of his career.

One tribute referred to Birley as "the caring face of psychiatry", and those who knew him would readily testify to his warmth and humour. He championed the cause of social psychiatry, having spent three years at the Maudsley's MRC Social Psychiatry Unit. He learned much from Douglas Bennett on how to take social psychiatry from the blackboard into the real world. He became a consultant at the unit in 1968 and helped engender an ethos of what he later called "buck stops here" psychiatry, whereby the patient, often living locally, had their needs catered for on the spot with the help of the appropriate social structures.

Among these was the Windsor Walk Housing Association, which provided houses for loose-rein supervised accommodation. Birley secured the first house with a deposit from a local philanthropist, persuaded the council to provide the rest of the mortgage and had the residents in within months. Three more followed in the next four years, with more later. The revolutionary schemes involved houses with multiple occupancy and, instead of an authority-figure "warden", employed a manageress who lived locally. People would be treated as far as possible as residents rather than patients, and given as much opportunity as possible to live an autonomous life unhindered by family ties.

"These houses gave people their own space and much more freedom," he later observed. "They were expected to act responsibly in the house and indeed they did so, coping well with the crises which occurred there." This was unlike in a mental institution, said Birley, where people's natural capacities atrophy because they are never tested. "It was quite novel, in those days, to set up a house like this without any resident staff. But we were determined to do that and never regretted it." The association is in existence to this day.

Birley's own research made a major contribution to early studies showing how "life events" can be associated with the onset of psychiatric disorders. In 1960 he had conducted research which showed how patients suffering from psychotic attacks were likely to have recently undergone some sort of crisis. He noted with wry amusement years later that, so far-fetched was the notion that schizophrenia could be precipitated by a life event, the British Journal of Psychiatry rejected his article. But the American Journal of Health Behavior ran it, and it became the set text on the subject.

Birley also founded the Southwark Association for Mental Health. One facet of this was vigorous fund-raising at the local fête, held on the (now built-on) lawn of the Maudsley, which raised considerable sums and, in typical Birley fashion, persuaded patients, staff and members of the public to drop their inhibitions and muck in. It would amuse Birley to recall that among the most popular attractions was the fortune-teller, supplied by the Maudsley's most disturbed ward. "The long line of clients waiting to hear their fate was largely composed of Maudsley staff," he recalled with his throaty laugh.

He also pressed for local catchment area services, expanded outpatient and community services as an alternative to long-term institutional care. He ran the Maudsley's Emergency Clinic, which some felt got local GPs off the hook by providing a walk-in service. But research suggested that those referred by GPs tended to be less ill than those who came spontaneously, so it was serving its purpose. He was also the moving spirit behind the Thorn Nursing initiative, a training curriculum for community psychiatric nurses that aimed to include family and patients in deciding best care. The Maudsley's 18-bed facility for acutely ill women bears the name the Jim Birley Unit. He was later a part-time adviser to the Samaritans.

His main task was in confronting the Thatcher government at its most ideologically driven. "All of us, once we had read Working for Patients, realised that it had been written by people who didn't understand the NHS," he said. "Struggling with a government who quite clearly hadn't thought it out and weren't prepared to listen was a very unnerving experience." He failed to see the logic of encouraging both care and competition, which "results in Bradford providing care for learning disabilities in Surrey", and he spoke forcefully about the effect on morale and recruitment.

The latter stages of his career will be associated mostly with his work in the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc. In 1989 he represented the World Psychiatric Association, showing steel and diplomacy in persuading the Soviet delegates to admit to its political use of psychiatry in the past. The USSR was readmitted under strict conditions, observance of which he continued to help monitor. He was prominent among those who sought to help a battered profession as the Cold War came to an end.

He retired from clinical work at the beginning of 1991. He and his devoted wife, Julia, left London for an enviable retirement on the Welsh-Herefordshire border, where he tended a vast and rich garden and catered for his encyclopaedic knowledge of flora and fauna. They were visited frequently by their children and 10 grandchildren, in whose memory – his godson presumes to testify – he, for all his professional brilliance, will live on as the most benign, lovely and fun grandfather.

James Hanning

James Leatham Tennant Birley, psychiatrist: born London 31 May 1928; Dean, Institute of Psychiatry 1971–82; Dean, Royal College of Psychiatry 1982–87, President 1987–90; CBE 1990; married 1954 Julia Davies (one son, three daughters); died 6 October 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments