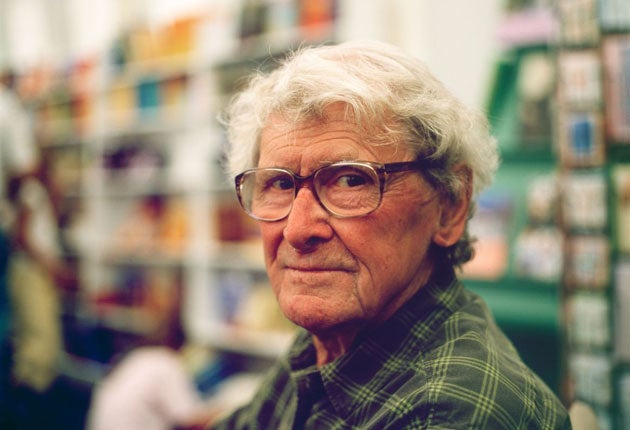

Dick King-Smith: Late-blossoming children's author whose tales of the countryside sold in their millions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The bestselling author of animal-based stories of his times, Dick King-Smith was a stylist as well as an instinctive storyteller. Drawing on his classical education, he never used 10 words when five would do, producing stories that were models of literary economy. Sticking mostly to what he termed "farmyard fantasies", he still made sure that his talking animal characters stayed as close as possible to the realities of agricultural life. Quizzically ingenious and unfailingly good-humoured, his books were a natural choice for younger readers looking for a good tale.

Born in a corner of the Gloucester countryside where he was to stay for most of his life, Dick – christened Ronald Gordon – was the eldest son of an affluent paper-mill owner. His nickname arose from a remark made to his nanny one day, advising her to look at the dicky birds in the sky in an attempt to divert her from seeing him crying over a scraped knee. He soon had a number of pets, determining early on to be a farmer, which would mean he could look after more animals. But first there was prep school and then Marlborough College. Working after that as an apprentice farmer at a small holding in Wiltshire, he was helped along by sympathetic, older workmates still following immemorial countryside ways. Their speech, mannerisms and range of skills were recorded by him years later in his endearingly meandering autobiography Chewing the Cud (2001).

In 1941 King-Smith enlisted in the Grenadier Guards. Marrying his childhood sweetheart, Myrle, in 1943, he saw action in Italy the same year, barely surviving serious injuries caused by an exploding British grenade lobbed back at him by the other side. Saved by the new wonder drug penicillin, it took him around two years to fully recover. By that time there was a daughter, Juliet, followed three years later by Betsy.

After attending an agricultural course set up for ex-servicemen, King-Smith settled into Woodlands Farm in 1948, acquired for him by the family business with the intention that he could then supply the mill canteen with milk and eggs. Surrounded by a miscellaneous collection of farm animals bought on the cheap, King-Smith worked hard, happily but unprofitably. Never concentrating on one speciality, he treated his stock as an extension of the beloved pets he owned when young, each valued for their own particular personality but none of them effective cash-earners. In 1961 he moved to a larger farm, no longer buttressed by family money. Six years later the whole operation went bust.

By now the father of three children, King-Smith was faced by the urgent need to earn money by some other route. Employment as an unlikely travelling salesman was followed by a spell as a work-study engineer in a shoe factory. Neither experience was successful. Finally, aged 49, he trained to be a teacher, going on to work for seven years at a nearby village primary school. Already contributing light verse for Punch, he moved on to children's books with The Fox Busters (1978), published to immediate success. An affectionate pastiche of the film The Dam Busters, it featured militant hens making an ultimately triumphant stand against their old enemy the local fox. More stories followed, also well received. But it was the publication of his famous The Sheep-Pig (1983) that changed King-Smith's life for ever.

Winner of the Guardian Award for children's literature, this novel drew on King-Smith's long experience of working with pigs, animals he both liked and respected. But Babe – the young hero of the title – lives in a much tougher world than the one inhabited by popular porcine characters in the stories of Beatrix Potter and Alison Uttley. Every animal on the farm other than Babe knew that his life was destined to be short. But by showing how it was possible to herd sheep using respect rather than aggression, Babe finally wins everyone over. Add in an exciting adventure seeing off rustlers, plus a near-fatal misunderstanding resolved in the nick of time, and here was a story destined to become a classic. The film version of the book, Babe, produced by Universal Pictures and released in 1995, was also a huge hit. After a lifetime of money worries, King-Smith could at last afford to take things easy.

In fact, the opposite happened. Producing around ten books a year, he now had the writing bit well between his teeth. Never afraid to be didactic when he thought the occasion demanded, and regularly returning to plots where Cinderella characters still manage to win out by the end, writing came increasingly easy to him. Sophie's Snail (1989) proved particularly popular, featuring an engaging small girl living in the countryside and intent on farming as a career. This character was based on how King-Smith imagined his wife, Myrle, to have been as a child; the book was the first of a series of six.

Not every story ends on a note of happy fulfillment. Godhanger (1996) describes how a cruel gamekeeper who tyrannises all the animals in Godhanger Wood is defeated by the mysterious white eagle Skymaster, who sacrifices his own life in the process. Written for older children with an intensity that recalls Richard Jefferies' neglected fable Wood Magic, this book took King-Smith's fictional range into new directions. It was followed by his equally impressive The Crowstarver (1998), a moving story about a slow-witted country boy whose love of animals illuminates a life destined to end in tragedy. Set in the recent past, it is packed with affectionate descriptions of working practices now disappeared. There were too occasional excursions into poetry, in particular Alphabeasts (1990), consisting of nonsense poems offering a light-hearted introduction to the alphabet, illustrated with all his usual brio by Quentin Blake.

For much of this late-blossoming time King-Smith also enjoyed another career as a children's television presenter. In 1983 he appeared on Anne Wood's morning show Rub-a-dub-tub, filmed in the company of various creatures, from badger cubs to white tigers. After 50 episodes, he was then taken on by Channel 4 for Pob's Programme, a televisual treasure hunt within which King-Smith and a Labrador dog followed various clues in their attempt to find whatever had been hidden away that week. After that, Yorkshire TV's Tumbledown Farm continued with the hands-on animal theme, ending each week with King-Smith telling a story while his dog dozed by the fire.

Author of over 100 books, translated into 21 different languages with sales in the millions, Dick remained an essentially modest man, delighting in his success while slightly disbelieving in it at the same time. A handsome, erect figure, he lived for years in a small 17th-century cottage near Keynsham, Avon, tucked out of the way between Bristol and Bath and only three miles from where he was born. Frequently visited by grandchildren and great grandchildren, he was popular with all who knew him. After Myrle's death in 2000, he subsequently married Zona, an old family friend. Still writing almost to the end, with The Mouse Family Robinson appearing in 2007, he was awarded an OBE in the 2010 New Year's Honours List.

His death deprives children of one of the last authors with experience of the British countryside as a traditional working community. They have also lost someone who always told a good story in prose, whose every sentence consistently rang true.

Nicholas Tucker

Ronald Gordon "Dick" King-Smith, children's author: born Bitton, Gloucestershire 27 March 1922; married first 1943 Myrle (two daughters, one son); second Zona; died near Bath, Somerset 4 January 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments