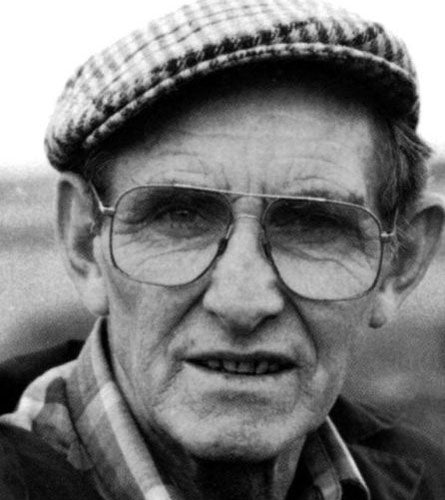

Dic Jones: Archdruid of Wales and master poet in the strict metres of Welsh prosody

When Dic Jones won the Chair at the National Eisteddfod in 1966 he was hailed as a master of the traditional metres whose like had not been seen since medieval times. By this was meant he wrote cynghanedd – the intricate system of metrics, syllable counts and rhyme which Gerard Manley Hopkins called, somewhat inadequately, "consonantal chiming" – and with such brilliance that he could be compared with poets like Dafydd ap Gwilym, a contemporary of Chaucer, whose work is one of the chief glories of Welsh literature.

The poem which brought him prominence on a national stage was entitled "Cynhaeaf" ("Harvest") and it was praised by one of the three adjudicators, Thomas Parry, the sternest of critics, for its consummate craftsmanship and rich imagery drawn from the poet's observation of the natural world and the passing of the seasons. When Dic Jones came to publish his second volume of verse three years later, it was natural that it should take the title of his magnificent poem, "Caneuon Cynhaeaf" ("Harvest songs"). His reputation as Prifardd, or Chief Poet, was now made and he took his place among the most accomplished Welsh poets of his day. To the post of Archdruid, to which he was appointed in 2008, he brought a ready wit and an impressive stage presence which relied on his rugged countenance and broad grin.

It would be a mistake to remember Dic Jones merely as a bardd gwlad or country poet, a rhymer on bucolic themes with straw behind his ears, for he was heir to a centuries-old tradition as sophisticated as, say, that of the Jocs Florals in Provence or the poetry of the great makars of Scotland such as Dunbar and Henryson. Technical virtuosity may be at its heart but it also has room for a world-view that is as much intellectual as it is lyrical. Dic Jones wrote poems in which he addressed famous politicians and commented on the wonders of technology such as the Telstar space satellite and the military base at Aber-porth.

Dic Jones farmed Yr Hendre at Blaenannerch near Aber-porth in lower Cardiganshire, as his people had done for hundreds of years. He knew himself to be a poet while still a pupil at the Cardigan County School and was soon taken under the wing of Alun Cilie, a member of a famous family of poets who lived at nearby Llangrannog, and it was he who tutored the budding poet in the craft of Welsh prosody. It was not long before Dic Jones could turn out a perfect englyn, the four-line poem that is as precise as the haiku or tanka, except it has rules of alliteration, stress, consonant-count and rhyme that make the Japanese forms seem crass in comparison. One simple example, about the Christmas tree, must suffice:

Pren y plant a'r hen Santa – a'i wanwyn

Yng nghanol y gaea',

Ni ry' ffrwyth nes darffo'r ha',

Nid yw'*ir nes daw'*eira.

("The children's tree and old Santa's, its springtime is in the middle of winter, it bears no fruit until summer is over, it flourishes only when snow has come.")

Like many poets who are devoted to the form, Dic Jones had hundreds of englynion by heart; make that thousands, for there seemed to be no bottom to the well from which he drew inspiration. So adept was he that his conversation sparkled with whole sentences in cynghanedd and witty couplets in seven-syllabled lines which he composed at the drop of a hat. There may be something mathematical about the requirements of the craft -- it can be learned in a few years by a gifted amateur – but the master-poets, of whom Dic Jones was one, rise above the form's restrictions and makes their verses sing. Many of his shorter poems (he also wrote epigrams, limericks and topical ballads) rely for their effect on humour and satire and he could always be relied upon to cause laughter among his listeners.

For this reason he was in constant demand at weddings and parties, and when asked for a celebratory poem on any occasion, large or small, he would readily oblige, thus carrying out the function of the country poet that has for long enlivened the cultural ambiance of rural Wales. On his own behalf, he wrote a poem requesting a loan from his bank, another greeting his fellow-poet T. Llew Jones, in hospital after an accident, and another protesting about a rise in water-rates, all in immaculate cynghanedd and to a high standard. One is hard put to think of any other language in which literary activity of this kind is the norm.

Dic Jones first came to public notice by winning the Chair in five consecutive years at the Eisteddfod held by Urdd Gobaith Cymru (Welsh League of Youth), but unlike many youngsters who carry off that prize he went on to fulfil his early promise by publishing his first collection, Agor Grwn ("Cutting a furrow"), in 1960. It was followed by Storom Awst ("August storm", 1978) and Sgubo'r Storws ("Clearing out the storehouse", 1986). Many of these poems celebrate the close-knit communities of Cardiganshire, giving the lie to the hate-writing of Caradoc Evans who, a generation or two before, had pilloried them for their grudging soil, brutish peasantry and perverted religion.

There is something joyous and uplifting about Dic Jones's portraits of his neighbours, their dogs and livestock, and even their machinery, for he wrote poems extolling the Ffyrgi and the Jac Codi Baw – the Fergusson Massey tractor and the JCB that have brought such improvements to the ways the land is worked. His example reminds us that poetry is not always written out of a tortured or neurotic mind but is sometimes produced by a sunny temperament and an uncomplicated lifestyle close to the soil and the elements.

Two events cast a cloud over the serenity of Dic Jones's view of Wales and the world. The first was the death, at three months, of his daughter Esyllt, a Downs Syndrome child, and the controversy that followed a most unfortunate mix-up in the Chair competition at the National Eisteddfod of 1976, an important occasion since it was the eighth centenary of that venerable festival. The adjudicators chose his poem on the subject "Gwanwyn" ("Spring"), submitted under a pseudonym as usual, as the best in the competition but, because it turned out he was a member of the Literature Panel and had thus had fore-knowledge of the set subject, he was disqualified and, at the very last moment, the Chair was awarded to a reluctant and dark-browed Alan Llwyd.

Acrimony followed and opposing camps emerged, the incident doing considerable damage to the amour propre of both poets and showing up a degree of administrative bungling on the Eisteddfod's part. Dic Jones took such setbacks with the dignity of the true poet: "When a man manages to write a verse that is completely to his liking, or a couplet he can recite to himself as it brings a tear to his eye, he knows deep down that it makes no difference what any adjudicator, or anyone else, says of it. He has received his prize and will spend the rest of his life trying to savour again that fleeting moment."

Dic Jones's last years were taken up in trying to find ways of maintaining Yr Hendre against the ravages of the foot-and-mouth epidemic and the myriad difficulties facing the farming industry. One of his initiatives was to hire out part of his land for summer visitors who were put up in teepees under the supervision of one of his sons, Brychan Llyr, a well-known pop musician. A muscular man, with a handshake that made strangers wince, Dic Jones never lost his sense of humour, his delight in choral singing, his social obligations and his devotion to the craft of poetry. Many younger poets sought him out and he continued to take part in the popular poetry contests held annually in the Literature Pavilion at the National Eisteddfod. He became Archdruid of Wales in 2007 but officiated only once, at the Eisteddfod held in Cardiff in 2008, and illness prevented him from taking part in the ceremonies at Bala this year.

He gave an account of his life up to 1973 in Os Hoffech Wybod ("If you'd like to know", 1989) and published a last collection of topical poems and articles, Golwg Arall ("Another view", 2001), which he had contributed to the weekly magazine Golwg. The title of his autobiography has resonance for Welsh readers for it is a quotation from Ceiriog's famous poem, "Alun Mabon", which reads (in translation): "If you'd like to know how a man like me lives: I learned from my father the first craft of humankind." Dic Jones may have been, by his own admission, an indifferent farmer, but as a poet he takes his place among the finest practitioners of an art that rewards them with everlasting renown – everlasting, that is, for as long as Welsh remains a language in which literary genius can find expression.

Meic Stephens

Richard Lewis Jones (Dic Jones), farmer and poet: born Tre'r-ddôl, Cardiganshire 30 March 1934; married 1959 Siâ*Jones (three sons, two daughters and one daughter deceased); died Blaenannerch, Ceredigion 18 August 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments