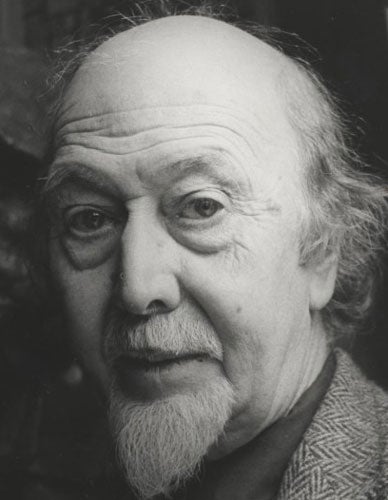

Desmond MacNamara: Pivotal figure in Bohemian Dublin

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Desmond MacNamara, artist and writer: born Dublin 10 May 1918; married first Bevelie Hooberman, secondly 1953 Skylla Novy (two sons); died London 8 January 2008.

Desmond MacNamara was born in 1918 in Mount Street Crescent in Dublin, in the shadow of the beautiful St Stephen's Church, affectionately – if irreverently – known by locals as "the Pepper Canister Church". A quiet Georgian backwater between the elegant Merrion Square and the tree-lined Grand Canal, it was an appropriate birthplace for the future artist.

Thirty years later, this area would be the centre of the Bohemian quarter known as "Baggotonia", in which MacNamara would play a pivotal role. Its inhabitants would include such diverse characters as the playwright Brendan Behan, the poet Patrick Kavanagh, the novelist Flann O'Brien, the artists Jack Yeats, Patrick Pye and Owen Walsh, and the sculptor John Behan.

After the early death of Desmond MacNamara's father, his mother set up as a couturier. She encouraged her son's artistic interests and he studied sculpture at the National College of Art in Dublin, as well as becoming involved with a progressive theatre group.

Politics ran in the MacNamara family; Desmond's grandfather had participated in the Fenian uprising. Desmond MacNamara worked with the veteran socialist Peadar O'Donnell, and it was on a Spanish Civil War demonstration that he first met the 16-year old Brendan Behan – "Despite a very bad stutter and a very broad Dublin accent, he was even then a very loquacious young man."

MacNamara started to make a precarious living from producing papier mâché sculpture and props for the Abbey and Gate theatres, and for the odd movie, such as Laurence Olivier's Henry V (1944), which was filmed in Ireland. His studio at 39 Grafton Street was a hospitable place where his first wife, Bevelie Hooberman, kept a constantly bubbling coffee-pot which soon attracted a procession of impecunious but talented guests.

The studio evolved into a literary salon where Mac, as he was known to his friends, introduced would-be writers and artists to publishers and potential benefactors, and calmed the most recalcitrant with his ready wit. He introduced Behan to John Ryan who published the newly released prisoner in Envoy magazine, and also to Alan and Caroline Simpson, who first staged The Quare Fellow, which catapulted Behan on to the London and world stage.

Other visitors included the writer J.P. Donleavy and Gainor Crist (the model for the central character in Donleavy's The Ginger Man), the actor Dan O'Herlihy, the novelist Ernest Gebler and the exiled mathematician Erwin Schroedinger. "Gainor Crist was much nicer than he appears in the Ginger Man book," said MacNamara. "He was also a bit of a rapscallion and quite recognisable as the Ginger Man." MacNamara himself was portrayed as the generous "MacDoon" in The Ginger Man; "Small dancing man. It is said that his eyes are like the crown jewels."

The overflow from the MacNamara salon trickled across Grafton Street to a spit-in-the-sawdust pub in Harry Street. Within a short time, McDaid's was established as Dublin's leading literary pub. Sharing the counter and disputations with MacNamara would be Behan, O'Brien, the poets Patrick Kavanagh, James Liddy and Val Iremonger, and the former revolutionary Tony McInerney.

MacNamara started to frequent London in the early 1950s. "I did a lot of toing and froing at that time," he said. "I'd go for one or two months, then six months." He gradually put down roots in London, finally settling in West Hampstead with his new wife, Skylla, a publisher's editor who also knew many of the Irish writers. Skylla recalled; "We were married in 1953 and Mac was thrilled to find that James Joyce had also married in the same Kensington Registry Office."

But Desmond MacNamara hadn't seen the last of his Irish friends. "Brendan Behan stayed with us most times he was over," he said. "I remember once having to bail him out of a West End police station. When I arrived, I found Brendan and all the police having a party around two crates of pale ale."

A frequent visitor to Paris, MacNamara met Samuel Beckett when the pair of them helped the young sculptor, Hilary Heron, who had been injured in a motorcycle accent. "Sam pointed out a jeep in the street," said MacNamara.

"The best form of transport," he insisted.

"Why?" I asked.

"Look. No seats, no roof. That's it, the most basic form of mechanical transport."

As well as continuing his sculpture, MacNamara taught art at the Marylebone Institute. He also found time to write a biography of Eamon de Valera and an acclaimed book on picture framing (Picture Framing: a practical guide from basic to Baroque, 1986). In 1994, he published the fantasy novel The Book of Intrusions, which he followed two years ago with Confessions of an Irish Werewolf.

Brendan Lynch

Desmond MacNamara was a lifelong vegetarian, always careful of everything he ate and drank, writes J.P. Donleavy. One always felt certain he would not meet his maker until he was at least a century old, and even then be fully ready to live another one.

My files of his letters attest to his being a great correspondent, as well as one's Official Gossip Keeper. He was part of Dublin's underground culture and one of its true Bohemians in the years after the Second World War, when the city, without shortages and with Guinness aflow, became a cornucopia of earthly delights. Yet, this dear man always remained dignified in the manner in which he conducted his life.

He was scrupulously well-mannered and behaved, but could, if crossed, be one of the world's greatest wielders of creative revenge, nearly rivalling his trusted friend Brendan Behan, who had no peer in getting even with people. Behan and Mac were close associates long before Behan, tongues of his shoes hanging out, was by dint of world fame welcomed into polite society (but, let it be said, Behan would have barged in anyway).

Desmond MacNamara

by Frank Gray

Desmond MacNamara was probably Brendan Behan's best friend, providing the noisome Irish playwright with timely injections of friendship when Behan most needed it. Although a calm man by comparison, MacNamara was not above mischievous ideas of his own. On the mantelpiece of his Hampstead dwelling stood a life-sized brass bust of Behan, his jaw jutting, his hair tousled and his nose thrust forward like a hatchet as if ready to strike. Having got Behan to pose for the sculpture back in the late 1950s, MacNamara wondered what to do with it.

The two men settled on using the Behan likeness to supplant one of the many tedious sculptures dedicated to long-forgotten civil servants that clutter London's municipal parks. The belief was that no one would notice the ruse and that Behan would at the same time be immortalised.

Several attempts were made to site the likeness but the project was abandoned, because lugging it surreptitiously from home to site proved too awkward. At least, MacNamara once said, the sculpture shows what Behan looked like in his heyday.

Behan, although banned from visiting Britain due to IRA activity during the war years, became a regular at the MacNamara household in London. But Behan's success with The Quare Fellow and The Hostage and the autobiographical Borstal Boy came at a high price. MacNamara remembered that their last visits were disturbing encounters, filled with recrimination, accusation, anger and tears. The two men had been out of contact for some months when MacNamara, then in Rome, heard of Behan's death, of the effects of alcoholism, in 1964.

In an interview in 2007, MacNamara said: "I tend to measure my friends by thinking of something I want to tell them. I say to myself, 'I must tell so and so that', and this was frequently the case with Brendan, and then I suddenly realise that I cannot, for they are no longer here . . . There is a very small number of such people, and Brendan was one of them."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments