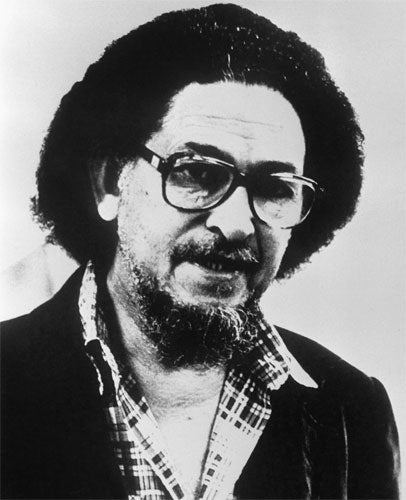

Dennis Brutus: Activist whose efforts helped bring about the end of apartheid

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The story of the ending of white racial supremacy in South Africa has for its cast men and women in political, church, cultural and other such groups whose members mostly ended in prison or exile in the 40-year struggle. Was there another case, like that of Dennis Brutus, of an individual who built up on his own personal initiative and toil a process which brought the evils of apartheid to a world-wide constituency and bit by bit won its war against the perpetrators of apartheid and their complacent, blinkered allies in many countries? Was there a man who actually forced the South African government to yield, at a high price to himself and at the cost of much suffering?

Dennis Brutus, a teacher in his thirties in a school for mixed-race children in Port Elizabeth, had learned about liberation politics at blacks-only Fort Hare University, where, funded by the family's Catholic priest, he took his BA in 1947. In his teaching job he kept clear of the African National Congress and its multi-racial allies, the Liberal Party and the Trotskyites, certain that he could run his own campaign more effectively independent of them. His objective was to open up South African sport, at home and abroad, to spectators, administrators, and media people of all races, and in the process to bring the anti-apartheid struggle before millions scarcely aware of it.

In 1958 he founded the South African Sports Association, dedicated to breaking the whites-only monopoly of South African sport, the exclusion of people of colour from national teams and the colour bar imposed on visiting teams. He recruited as patron the universally admired writer and liberal Alan Paton and constructed a committee of which he was secretary, but which scarcely ever met. Dennis Brutus was SASA, from which, running on small donations, the photocopier of a local liberal NGO, no office and no staff, he took on the deeply embedded racially discriminatory South African sports establishment.

At the 1959 Liberal Party congress Paton, the President, himself proposed the abandoning of the forthcoming tour of "Mr Worrall's cricket team from the West Indies". The opposition got through to the Caribbean and the tour was cancelled, as was the All Blacks rugby tour the following year. A Brazilian football team cancelled its Cape Town visit when SASA and the Liberals made it clear that its black players would not be allowed on the field with whites. The movement grew mightily and in 1961 Brutus set up the South African Non-racial Olympics Committee (SANROC): the fight was on to exclude a whites-only team from the Olympics, with activists like Chris de Broglio, John Harris and Sam Ramsamy sharing his huge task.

Dr Verwoerd's government caught up with Brutus that year and a banning order put a stop to his social and political activity, his writing and organising. Escaping to Swaziland, he was caught by the Portuguese police on the Mozambique border on his way to a meeting of the International Olympic Committee in Europe and taken back to South Africa. He briefly escaped his captors in the streets of Johannesburg and was shot in the back. It was a close call: a blacks-only ambulance arrived after some delay.

Sentenced for evading his ban, he spent 18 months on Robben Island. A fellow prisoner, Eddie Daniels wrote: "Dennis Brutus was systematically and vilely persecuted, so badly that at one stage he became psychologically disorientated. On his release he gave a press conference in London in which he gave an account of the brutalities on the Island. Unfortunately, he was accused of exaggerating. He was not exaggerating but telling the unvarnished truth" (There and Back: Robben Island 1964-1979, 1998).

It was an act of folly by Minister of Justice Vorster that he was allowed to leave the country, albeit on a one-way exit permit. Supported by, and assisting, Canon Collins's Defence and Aid Fund, he made gains for SANROC. South Africa was barred from the 1964 Games in Tokyo and all subsequent Games until Barcelona in 1992, though not expelled from the International Olympic Committee until 1970. He also worked closely with Peter Hain and his "Stop the Tour" campaign to disrupt the rugby and cricket tours to Britain.

In 1963, while he was in prison, a collection of his poems, Sirens, Knuckles, Boots, had been published by Mbari, Nigeria, followed by Letters to Martha (London, 1968) and nine more collections of his verse, the most recent being Poetry and Protest (Chicago, 2006). His literary reputation grew and in the new field of African literature he soon found academic distinction at a series of American universities, with professorships at Northwestern (Evanston, Illinois) and Pittsburgh before retirement. It was not all plain sailing: in the early 1980s he won the right to asylum in the US after lengthy litigation when the Reagan administration changed the rules.

His poetry was little known in South Africa: thanks to the censor only Thoughts Abroad (1975), by the pseudonymous John Bruin, evaded the censor, until Brutus's ban was lifted at the time of the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990.

He came back to South Africa for the first time in 1993, settling in Cape Town in more recent years. His independence of the ANC in his sports- campaigning years sidelined him but he was recognised by many as the man who had actually caused the Afrikaner Nationalist government to accept defeat and make changes. His literary fame outweighed this and he lectured at South African universities and conferences and received eight honorary degrees in Africa and America. The ANC government recognised him with a Lifetime Achievement award but he refused to be honoured in the Sports Hall of Fame as it placed "those who championed racist sport alongside the genuine victims". He called for overdue "truth, apologies and reconciliation" in the sports community.

Brutus had identified the transnational corporations as the backers of the colour bar government and its allies. He pursued them in the Disinvestment Campaign in the US and later within South Africa and abroad. With apartheid long past, his Open Letter of 10 December to the UN Conference in Copenhagen on climate change received media coverage, with its warning against "a deal that allows the corporations and oil giants to abuse the earth". Ubiquitous to the end in human rights and African literature gatherings, Dennis Brutus, like an Old Testament prophet with flowing beard, aquiline features and that measured vocal articulacy of his, will be long remembered.

Randolph Vigne

Dennis Vincent Brutus, human rights activist, poet and academic: born Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe) 28 November 1924; married 1950 May Jaggers (four sons, four daughters) died Cape Town 26 December 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments