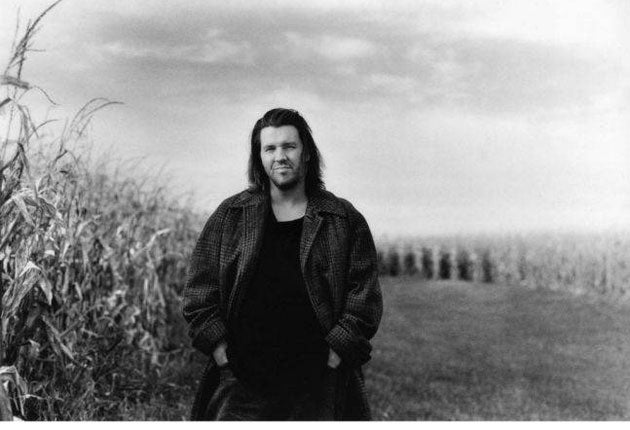

David Foster Wallace: Author of 'Infinite Jest' who many regarded as a writer of genius

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."It's odd," David Foster Wallace once said. "I don't really think of myself that much as a writer. I think of this as kind of an experiment that's going OK right now, and we're going to have to see what happens."

If Wallace, who committed suicide last Friday, was unsure of his own professional status, there was little doubt among his readers and critics that this man was a writer, all right: and not only a writer, but one of the foremost of his generation – the most influential, the funniest, certainly the cleverest, and to some minds, the greatest. But even as we might dispute his typically self-deprecating assessment of his claims, it is not hard to see the source of that sense of himself.

Even Wallace's critical detractors would not dispute that he was some kind of genius, capable of verbal pyrotechnics of such originality that he truly merited that over-used epithet. But before he became a writer, his prodigious brain made him a student of maths and philosophy who might have gone on to be a significant academic figure in either field: perhaps it is the mere good luck of those who love his work that, as it happened, he started work on a novel, instead.

Twenty-three years before he started on that first novel, Wallace was born in Ithaca, New York, in 1962, the son of a graduate student in philosophy and a grammarian English teacher. When he was six months old, the family moved to Philo, a "boxed township of Illinois farmland", where Wallace grew up playing high-level tennis – as a teenager, he was ranked in the top 100 in his age group nationally – and being groomed for the minimum master's degree that was, he said, as de rigueur in his family as medical school was in some others.

In his essay "Authority and American Usage", Wallace describes life as one of a family of SNOOTs, or "Syntax Nudniks Of Our Time": "Family suppers often involved a game," he explains, in one of his trademark footnotes: "if one of us children made a usage error, Mom would pretend to have a coughing fit that would go on and on until the relevant child had identified the relevant error and corrected it. It was all very self-ironic and light-hearted; but still, looking back, it seems a bit excessive to pretend that your small child is actually denying you oxygen by speaking incorrectly."

Wallace went to his father's alma mater, Amherst, and graduated summa cum laude in English and Philosophy in 1985. It was at Amherst that he began to write short stories, and his English thesis there became the basis for his first novel, The Broom of the System, which immediately marked him out to critics as a writer with the potential to be one of the definitive voices of his generation. It was published in 1987, and around the same time, according to his father James, Wallace started to take the medication for depression that he continued to use for the next two decades.

A book of short stories, Girl with Curious Hair, published in 1989, prompted Jennifer Levin in The New York Times Book Review to call him "a dynamic writer of extraordinary talent, one unafraid to tackle subjects large and small". But it was his next book, Infinite Jest, that cemented his status as one of the grand literary figures of his time. Wallace finished a draft in 1993, and spent the next three years cutting it down by a third to a modest 1,079 pages; the results were, by any definition, extraordinary. Infinite Jest, a sprawling, hectic, enigmatic, and totally incandescent book that is above all incredible fun to read, announced Wallace as maybe the first writer to combine the postmodern interests of Thomas Pynchon or Don DeLillo with the deep interest in character that might sooner be associated with a 19th-century novelist. Set in a near future where years are named after the highest bidder – "The Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment", "The Year of the Perdue Wonder Chicken" – it traces the lives of a teenage tennis prodigy, a recovering Demerol addict and burglar, and a group of wheelchair-bound Québécois separatists in hot pursuit of a video so entertaining that it puts its viewers in a vegetative state.

The book became notorious for its length, its 100 pages of footnotes and its ambiguous, closure-denying ending, but its many admirers saw it as the definitive American novel of the 1990s, brilliantly satirising the pop cultural miasma that Wallace saw engulfing his country. Deeply ironic, it nevertheless transcended its ironies in a way that may be seen as definitive of Wallace's voice: "Irony, entertaining as it is, serves an almost exclusively negative function," he once wrote. "It's critical and destructive, a ground-clearing. Surely this is the way our postmodern fathers saw it. But irony is singularly unuseful when it comes to constructing anything to replace the hypocrisies it debunks."

Wallace filled that space with a deeply sympathetic attention to his characters' myriad flaws – a 1,000-page argument for generosity that won him one of the prestigious MacArthur "genius" grants in 1997.

Wallace was somewhat bemused by the extraordinary response to his magnum opus. A part of him loved the attention, he said, but that part was never allowed to be in charge, and when paid literary compliments, he would respond by miming swallowing the tribute and defecating at the same time.

After Infinite Jest, he continued to work at Illinois State University, where he had taught creative writing since 1993, and published virtuosic, first-person journalistic essays that ranged from porn industry get-togethers to life aboard a cruise liner – the subject of what might be his best-known essay, "A Supposedly Fun Thing That I'll Never Do Again". He also published further collections of short stories and a "compact history of infinity". In his later fiction, the influence of his depression becomes more and more difficult to resist, and his last collection, Oblivion (2005), is consumed by a sense that life is something barely to be endured.

According to his friends and colleagues, neither that encroaching despair nor the magnitude of his gifts ever made him less gentle or humble a man with others. As well as "our strongest rhetorical writer," the novelist Jonathan Franzen said, "he was also as sweet a person as I've ever known and as tormented a person as I've ever known." And Verlyn Klinkeborg, a fellow teacher at Pomona College, where Wallace became the Roy Disney Professor of Creative Writing in 2002, said that "He had the very rare gift... of carrying the greatness of his ability intact within him and never letting it obtrude upon his colleagues. He was just a laborer in the field along with the rest of us."

In the last few years of his life, perhaps because of his depression, his output decreased, and he increasingly devoted himself to his students. Earlier this year he updated an essay written about John McCain in 2000, but, according to his father, he had reached what seemed like an inevitable end to his battle against depression. He took a leave of absence from Pomona, and made several visits to hospital this summer; but it was no good. His wife, Karen Green, found him at their Claremont, California home on Friday night. Wallace was 46. "Everything had been tried," James Wallace said, "and he just couldn't stand it any more."

Archie Bland

David Foster Wallace, writer: bornIthaca, New York 21 February 1962;married Karen Green 2004; died Claremont, California 12 September 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments