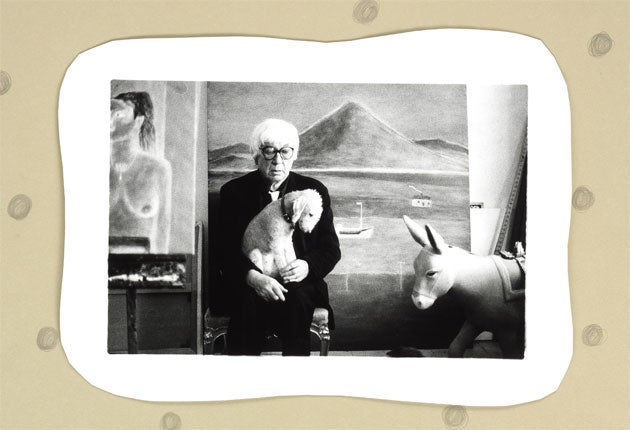

Craigie Aitchison: Painter renowned for his use of colour who refused to be tied down to a school or genre

For 50 years, the painter Craigie Aitchison drew on the same small repertoire of images: crucifixions, Italian landscapes, portraits of black men and pictures of dogs, usually Bedlington Terriers.

Not surprisingly, he had few imitators. All the same, Aitchison, who has died of cancer at the age of 83, was an immensely successful artist, with a devoted following among the great and good. Resistant to being tied down to a school or genre, he particularly disliked being described as naïve. But there was, in both his art and life, a childlike quality that won the hearts of those who knew him.

This was curious, as there was little in Aitchison's childhood to suggest a future as either an artist or an ingénu. He was born into Edinburgh's New Town aristocracy, his background firmly legal. His father, Craigie Mason Aitchison KC – the painter, christened John, later took his name – was Lord Advocate for Scotland and Labour MP for Kilmarnock. Educated at Loretto, the young Craigie-to-be was also groomed for the law. In 1948, he began eating his dinners at the Middle Temple, although he gave these up after two years in favour of a fine art course at the Slade.

There he met his lifelong friend, the painter Euan Uglow, a favourite of the school's director, Sir William Coldstream. Aitchison himself was viewed less warmly. "I was told by two visiting tutors, Victor Pasmore and John Piper, just to give it up," he cheerfully recalled, with characteristic lack of bile. When he copied a crucifixion by the still-living French Fauvist, Georges Rouault, a dismissive Slade professor sniffed, "This is far too serious a subject for you." Stung, Aitchison decided to persist with crucifixions, which he did for the next half-century.

This was all the more unexpected as he was not, in any conventional sense, a religious man. His explanations for his fixation were typically vague. "After my father dropped dead when I was 12, I read nothing but criminal cases," he said. "I didn't have time for made-up stories, because I was reading about murders... I mean, the things people do, honestly!"

Actually, Aitchison was 15 when his father died, but a taste for drink scumbled his background, like those of his paintings. His belief in Christ as an eternal victim was consistent, however, chiming with his own sense of exclusion from life's mainstream.

This may also explain Aitchison's taste for painting portraits of black men, which he excused in simple formal terms. Although he disliked being described as a colourist ("Everyone uses colour, don't they?" he once remarked), his pictures were almost always built up of thin, deeply saturated Expressionistic hues against which, he said, black skin looked better than white. His subjects included a nonagenarian boxer who had fought as the Chicago Kid, one Georgeous Macaulay and Aitchison's regular house-sitter in south London, Alton Peters.

A portrait of the last, bought by the Government Art Collection, hung over the desk of Chris Smith MP during his tenure as Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport. Unlike Smith and his fellow-painter of pugilists and crucifixions, Francis Bacon, Aitchison chose to keep his sexuality to himself.

This privacy, too, made his success surprising. In a time when celebrity became confused in the British mind with talent, Aitchison shunned the limelight. Not quite a colourist nor yet a naïve painter nor a Pop artist, his pictures seemed to come from nowhere. His analysis of his own work echoed the unnerving simplicity of the work itself. Questioned about the armlessness of Christ in his Crucifixion 9 (1987, now in the Tate), Aitchison remarked, "Everybody knows who He is. He doesn't need arms." As to the watching dog – a Bedlington, naturally – its role was to look as though "it was in a state about the situation". These answers, like the works themselves, added to the feeling that a Jungian drama was being played out on Aitchison's canvases; a story of infantile suffering in which words were replaced by archetypes and colours.

It was, perhaps, this sense of quiet tragedy that explained the longevity of his success. Aitchison showed his first crucifixion in a one-man show at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1959; he was still painting them when he died. And yet his fans never tired of them. The ex-critic of The Times recalled the artist turning to him at a Royal Academy dinner and yelping, "You're the one who said I was desperately in need of a new subject." Then, before the spluttering writer could reply, Aitchison continued, "And you're right, you know, you're right!" Yet he triumphed by becoming more and more like himself without slipping into self-parody.

Among his most recognisable traits was the use of saturated colours. Although these were already in his repertoire as a student – he had, he said, been "bowled over" as a child by a reproduction of Gauguin in his father's study – they were fed by his later love of Italy and the Italian Primitives, particularly Piero della Francesca. In 1955, Aitchison had used the money from a British Council scholarship to buy a London taxi and drive to Rome. It was the beginning of a lifelong affair with Italy, culminating in his buying of the farmhouse near Montecastelli in Tuscany where he passed long periods of his later life. After time spent there, his cadmium yellows would always be yellower, his royal blues more royal.

Earlier, in the 1960s and '70s, he had painted while on drugs – "You know," he helpfully explained to a startled interviewer, "LSD and all that, and amphetamines." These shaped Aitchison's palette until his need for them got out of hand, and he gave them up. For the last 30 years of his life, his main influences were whisky and Italy. Small, stooped and with a shock of white hair, he was, like his paintings, amiable and modest; although, like them, there was an underlying melancholy to him that hinted at something less happy.

John Ronald "Craigie" Aitchison, painter; born Edinburgh 13 January 1926; RA 1988, CBE 1999; died 21 December 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments