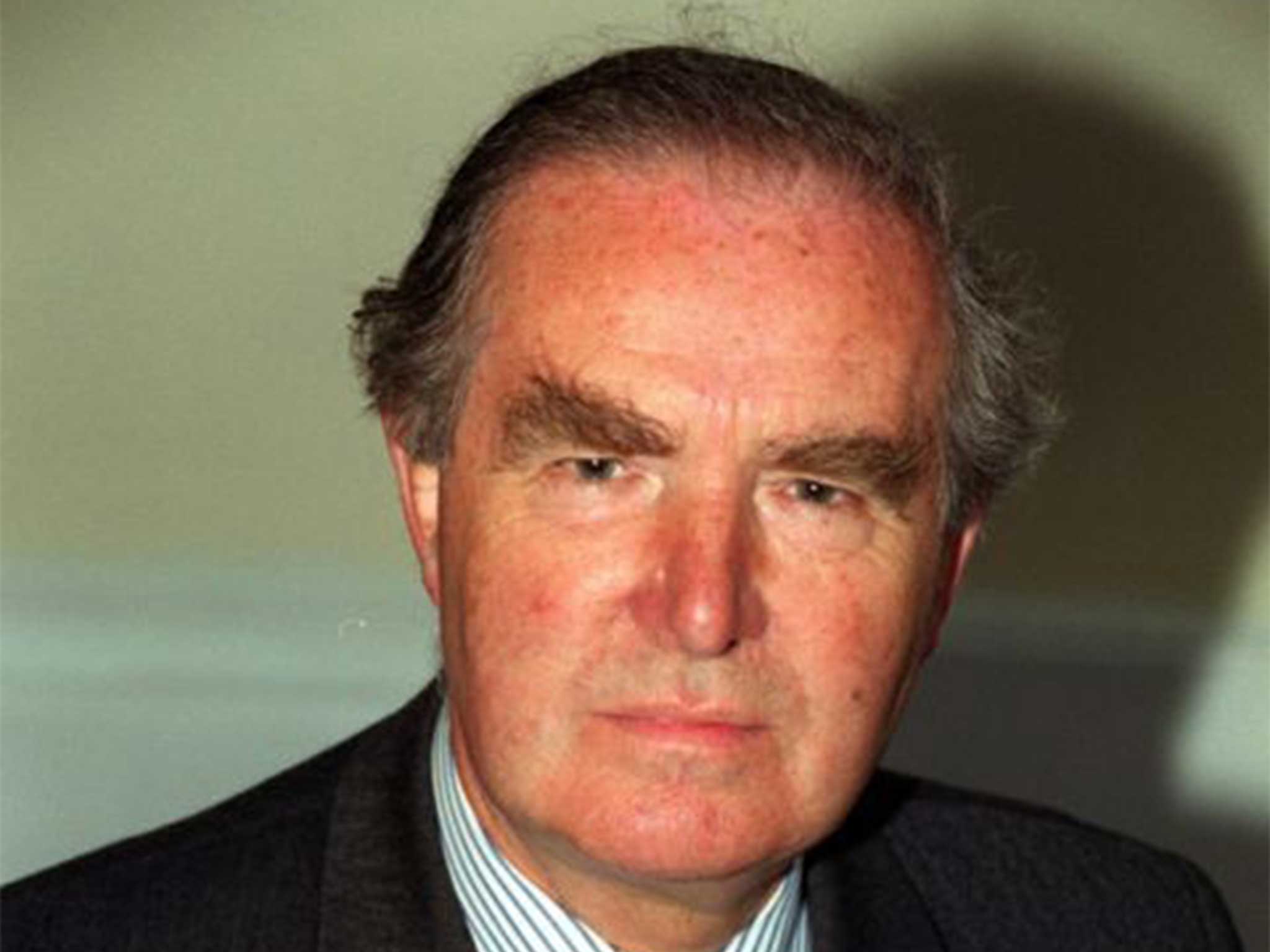

Clifford Boulton: Clerk of the House of Commons renowned for his meticulous way with parliamentary procedure

Boulton had an eye for detail and was extraordinarily swift to solve procedural difficulties in a commonsense manner

Clifford Boulton was Clerk of the House of Commons between 1987 and 1994 – and the esteem in which he was held was underlined by the former Speaker Betty Boothroyd, who told The Independent, "Clifford taught me well, as Speaker, and I owe him a huge debt of gratitude. He was a splendid Clerk. I was delighted to have inherited him from my predecessor, Jack Weatherill."

One of my abiding memories of Boulton is that when I was being awkward (but ever-polite) with Madame Speaker on points of order, he would slowly swivel in his chair at the table and hand clear written advice, however complex the subject under consideration.

Just after she retired from the Speakership, Boothroyd confided in me, as Father of the House, that the difficult early days of the first woman Speaker – for which no length of time as Deputy Speaker was entirely adequate training – were made infinitely easier by the quality – "and sympathy" – of the advice given to her by Boulton.

Clifford John Boulton came from a family of Staffordshire small farmers. His son, Richard Boulton QC, told me of the 50 cattle and pigs he remembers from his grandfather's holding. From Newcastle-under-Lyme High School, Boulton gained an Exhibition at St John's College, Oxford – but in those days, university tutors preferred to teach those who had done their National Service before going up to university, and Boulton was commissioned into the Royal Armoured Corps, serving in the Korean War.

Though he was the antithesis of a gung-ho cavalry officer, Boulton took his Army service seriously, later giving assiduously of his time to the Staffordshire (TA) Yeomanry. One of the few non-work related conversations I (or any MP) had with him was about the difficulties and dangers of our tanks' tracks being stuck in mud. It was all too clear that my problems with the British Army of the Rhine were as nothing compared to his in the Korean mud, with personnel who got out of the tank facing the perils of Korean or Chinese snipers. Boulton was a private person, to the point of shyness, about his achievements.

At the suggestion of his tutors at St John's, and encouraged by his local MP, Stephen Swingler – later one of the ministerial successes of the Wilson government – Boulton applied to the clerks' department in the House of Commons. Barnett Cocks, the Clerk Assistant, liked him, and he thereafter devoted his working life to the Commons.

He tepidly supported developments in the Select Committee system, which led to major reforms in 1979. He did not find his work for "subject" Select Committees congenial, being disinclined to be thought to be taking a line on issues of the day, which went against his concept of the impartial Clerk. It was this attitude, combined with an understandable rivalry with his talented contemporary Michael Ryle (Independent obituary, 13 December 2013), that brought him into conflict with champions of Parliamentary scrutiny, who saw him as a stick-in-the-mud – which he was not, merely cautious.

Boulton was in his element as Clerk of the Public Accounts Committee. His forte was as a highly effective performer in the procedural offices: he had a meticulous eye for detail and was extraordinarily swift to solve procedural difficulties in a commonsense manner.

This stood him in good stead, whether he was dealing with a difficult member (like me!) over the drafting of a Parliamentary Question in the Table Office, or making sense of a long list of amendments to a Bill in Standing Committee. From 1972-77, he occupied the most difficult position, Clerk of the Privileges Committee.

I got the impression that he had no time for politicians who mouthed off statements under the cloak of privilege inside the Chamber which they would never have made outside, for fear of the libel laws. On the other hand, Boulton was the first to champion the use of Privilege by MPs who had a genuine public-interest cause.

Successively Head of the Overseas Office, Principal Clerk of the Table Office and Clerk Assistant, Boulton was perceived as the very safest pair of hands. It was he who edited the 21st edition of Erskine May, the authoritative work on parliamentary practice, which crucially included a major revision of the index for the first time in years.

Boulton's retirement in 1994 chimed almost to the day with the setting-up of the Nolan Committee on Standards in Public Life; Lord Nolan paid public tribute to the contribution of Boulton, who was aware that the Commons would be doomed should it cease to take account of the opinions of the outside world.

Clifford John Boulton, Clerk of the House of Commons 1987-94: born Cocknage, Staffordshire 25 July 1930; CB 1985, KCB 1990, GCB 1994; married 1955 Anne Raven (one adopted daughter, one adopted son); died 25 December 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments