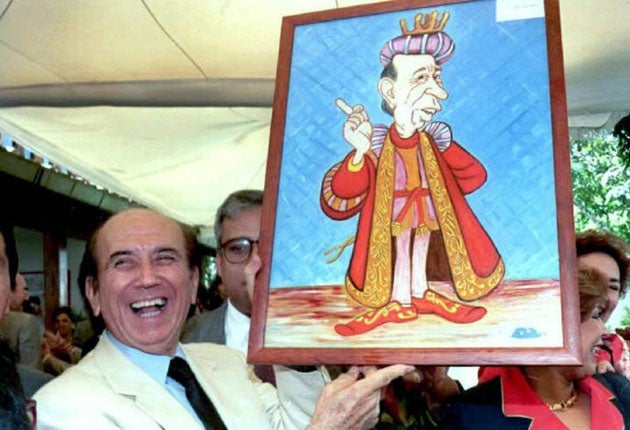

Carlos Andrés Pérez: President of Venezuela during the oil boom who was later forced out of office

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just as in the case of the current president Hugo Chávez, the Venezuelan presidency of the social democrat Carlos Andrés Pérez was never dull. He first led his nation from 1974-79 at the height of the oil boom when he nationalised the oil industry and the country became a world player with the nickname "Saudi Venezuela."

His second incarnation in the presidential palace, from 1989 to 1993, did not go so smoothly: his austerity measures caused street riots in which troops killed hundreds; Chávez, at the time an army lieutenant-colonel, staged an unsuccessful military coup against him in 1992; and in 1993, Perez was impeached and placed under house arrest for two years for siphoning off public funds into private accounts in New York. He died in exile in a Miami hospital on Christmas Day, attacking Chávez as a "dictator" until the end.

Chávez, his long-time nemesis, offered his condolences to the Pérez family in his own special way: "May he rest in peace. We send his relatives our regrets, and our wish that that old, egotistical way of doing politics never again returns to Venezuela." He said the family had "every right" to bury Péréz in Venezuela but they said they would do so only after Chávez was no longer in power. Chávez had previously accused Pérez, from exile, of plotting to assassinate him in 2003.

CAP, as Pérez became known to Venezuelans from his initials, was the epitome of the political animal and a natural-born survivor. Having studied law in Caracas, he decided against being a lawyer and went straight into politics, seeing it as a route to riches, fame and glamorous women. He became known for his bushy sideburns, his bespoke but always a bit too tight-fitting suits, a lifestyle which included an openly-flaunted, bling-bling mistress and a determination to make his little-known nation a player on the world stage – with himself playing the role of international statesman. In 1991, while both men were presidents, George HW Bush described Pérez as "one of the hemisphere's great democratic leaders."

While Pérez's glitzy style and nationalism attracted many Venezuelans – even the poor, who felt he was putting their country on the world map – the fact that his name began rising fast in business magazine lists of the wealthiest Latin Americans during the 1970s increasingly aroused suspicion as to where the money had come from. This was a fact that Chávez would later use against him, attacking Pérez as part of "the old, corrupt guard" during his own, eventually successful campaign to become president in 1998.

Péréz, of the social democratic Acció* Democrática party, was fortunate in that his first term coincided with the oil boom of the mid-1970s when the price per barrel rocketed. He nationalised the industry in 1976, as well as the holdings of American iron ore companies, turning him into a player on the world stage and an influential member of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting States (OPEC). An orgy of national mega-projects followed, including social programmes and construction of subways. The private sector boomed as a result and Venezuelans entered a period of glitzy consumption as never before, hence the nickname Venezuela Saudita, or Saudi Venezuela.

Péréz began portraying himself as leader not only of Latin America but of the Third World. He established diplomatic ties with Castro's Cuba, opposed the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua and backed Panama's efforts to gain sovereignty over the Panama Canal from the US.

But then oil prices began sliding, reports of high-level corruption spread – Péréz's mistress Cecilia Matos wore a gold necklace in the shape of an oil well tower (he was married at the time) – the foreign debt surged and capital flight towards the US reached an estimated $35bn. Despite the oil earnings, the country had gone from boom to bust. Pérez's successor, Luís Herrera Campins, said he had taken over "a mortgaged nation" and was forced to devalue the bolivar.

Having survived the corruption allegations during his first term, CAP the survivor was re-elected a decade later, in 1989, after a populist campaign slamming the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Once in office, however, he did a U-turn, borrowed $4.5bn from the IMF and launched an austerity programme and spending cuts while raising petrol prices at the pumps. Riots ensued in Caracas and were suppressed by gunfire from troops, killing hundreds in what became known as el Caracazo [the Big One in Caracas].

Péréz survived, as he did during two military coup attempts in 1992, one led by Lt Col Chávez, but he never quite recovered from the social upheaval. Venezuelans began resenting the fact that his mistress, Matos, appeared to have more influence than his government. In 1993, with a year of his term still to run, the Supreme Court impeached him for misuse of $17m of government funds, suspended him and in 1996 convicted him. After two years under house arrest, his survival instinct intact, he was elected senator in 1998 for his Andean home state of Táchira.

At the same time, however, his nemesis Chávez, who still blamed him for el Caracazo, became president and abolished the Senate, indeed the entire traditional political system. Péréz fled into exile, flitting between Santo Domingo, New York and Miami.

Carlos Andrés Pérez, the 11th of 12 children of a coffee farmer of Colombian origin, was born in the major coffee-producing town of Rubio, in Táchira state near the border with Colombia. On leaving school in 1938 he joined the Partido Democrático Nacional (PDN – the National Democratic Party) founded the previous year by the lawyer and journalist Rómulo Betancourt Bello and which would later become the Acció* Democrática. He married his first cousin, Blanca Rodríguez, in 1948.

He served as Interior Minister after Betancourt was elected president, overseeing a counter-insurgency against Cuban-backed guerrillas in Venezuela, before an ageing Betancourt backed his successful bid for the presidency in 1973.

Carlos Andrés Pérez, politician: born Rubio, Venezuela 27 October 1922; married 1948 Blanca María Rodríguez (divorced; six children), secondly Cecilia Matos (two children); died Miami 25 December 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments