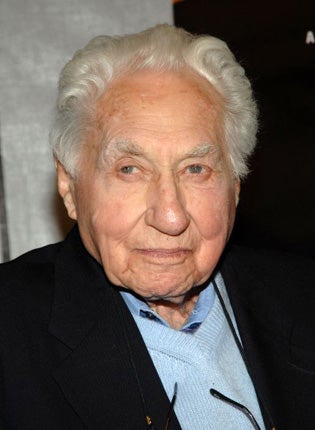

Budd Schulberg: Screenwriter who won an Oscar for 'On the Waterfront'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Budd Schulberg, who wrote the definitive book about ruthless Hollywood ambition, What Makes Sammy Run?, and who won an Oscar for scripting On The Waterfront (1954), was a true child of Hollywood. His father, B.P. Schulberg, who was head of Paramount Pictures from 1925 to 1932, thought up the sobriquet "America's Sweetheart" for Mary Pickford. Rudolph Valentino attended Budd's fifth birthday party, and his father's friends included Pickford, Charles Chaplin, Clara Bow, Cary Grant and Gary Cooper. His other books included The Disenchanted, based on the dispiriting period that writer F. Scott Fitzgerald spent in Hollywood, and The Harder They Fall, a hard-hitting expose of the boxing racket (Schulberg himself was an ardent fan of the sport, and was a close friend of Muhammad Ali).

His story, Waterfront, inspired by articles by Malcolm Johnson about the plight of dock workers, told the tale of a longshoreman and former boxer who testifies against the mobsters controlling the docks. It became the film On the Waterfront, in which Marlon Brando, as the rebel who once had to throw a fight, spoke the famous words to his gangster brother, "I could've had class. I coulda been a contender. I could've been somebody. Instead of a bum, which is what I am." Earlier this year, Schulberg gave his approbation to a stage version adapted by Stephen Berkoff.

If Schulberg's name is less familiar than it might be, it is doubtless because in 1951 he testified as a friendly witness to the House Un-American Affairs Committee, naming names of Communists, as did his friend, director Elia Kazan. Neither man was ever entirely forgiven by many of their associates.

He was born Seymour Wilson Schulberg in New York City in 1914. He was five years old when his father, offered the chance to handle publicity for the film magnate Adolph Zukor, moved his family to Los Angeles, where the precocious youth was allowed to roam the sets and witness the biggest stars in action, along with their off-screen demands and tantrums. He recalled that his laughter on a Marx Brothers set necessitated the scene being retaken. His best friend, Maurice Rapf, was the son of the MGM executive Harry Rapf, and Schulberg describes in his 1981 autobiography Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince how the pair watched the filming of the chariot race for the original Ben Hur (1925), and had fun, while hidden, throwing over-ripe figs at movie stars, once scoring a direct hit on Greta Garbo.

Schulberg credited his mother Adeline, a fierce supporter of the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, with stimulating his moral sense and intellectual prowess. "While she was carrying me, she spent as much time as she could in libraries, taking poetry courses at Columbia and reading Tennyson, Milton and Shelley, determined that I should become, at the very least, Stephen Crane and John Galsworthy combined." At the age of 10 he was being allowed by his father, who had graduated to producer, to sit in on story conferences and make suggestions.

His father's fame and fortune were to disappear eventually, due to alcohol, gambling and romantic affairs, and Budd was particularly concerned when his father fell in love with the young actress Sylvia Sidney, moving out of the house to live with her. One of her early roles was that of the hapless frump who becomes pregnant by social climber Clyde (Philips Holmes) in Josef von Sternberg's version of Dreiser's An American Tragedy (1931). After watching the scene in which Clyde takes the young girl boating with the intention of drowning her, Schulberg recalled thinking, "If only I could take Sylvia rowing in Westlake Park, tip the boat over, watch the little home-wrecker go down for the third time, and swim to shore insisting it was an accident. The perfect crime."

After graduating in 1931 from Los Angeles High School, where he edited the student newspaper, he attended Deerfield Academy for a year, then Dartmouth College, where he wrote articles for the college paper and received a Bachelor of Arts degree cum laude. Returning to Hollywood, he provided additional dialogue for movies, including A Star is Born (1937), before earning his first writing credit for Little Orphan Annie (1938), based on the popular comic strip, in which he included several boxing sequences. He then wrote a light comedy titled Winter Carnival (1939, in which a divorcee (Ann Sheridan) takes refuge from the press by hiding at Dartmouth College during its winter festival.

Told he was being given a collaborator to strengthen the material, he found himself paired with F. Scott Fitgerald. Both men were fired from the assignment after spending a weekend on a drunken binge, his experience with the fading author (who died the following year) forming the basis for his novel The Disenchanted (1950), which was dramatised for Broadway in 1958, with Jason Robards Jnr. and George Grizzard as the characters based on Fitzgerald and Schulberg.

When the leading publisher Bennett Cerf had read one of Schulberg's college articles while lecturing at Dartmouth, he told the young student, "This is awfully well written. If you think of writing a novel, come and see us." After his experience on Winter Carnival, Schulberg followed Cerf's advice, and the publisher suggested he expand a pair of magazine short stories he had written about a devious anti-hero, Sammy Glick. Titled What Makes Sammy Run?, the book caused a sensation, and the name "Sammy Glick" has become part of the language, signifying an unprincipled go-getter. The novel's cynicism and fearless account of the clawing, back-biting and betrayals that mark Sammy's rise to the top in Hollywood won praise from critics but was loathed by the film industry. Louis B. Mayer thought Schulberg should be deported, John Wayne described it as part of a Communist plot, Sam Goldwyn, for whom he was working, fired him, and Hedda Hopper told him, "How dare you!"

Schulberg found himself ostracised by the studios. Tellingly, the book has never been filmed, though it was presented twice on television (1949 and 1959) and in 1964 it became a Broadway musical, starring Steve Lawrence as Sammy, which ran for 540 performances. Though enjoyable, it possibly made Glick too much of a charmer, and Schulberg himself voiced concern recently, stating, "Young people today seem to admire Sammy. I find it rather disconcerting that it has become a hand-book for yuppies." Dreamworks announced their plan to film the book with Ben Stiller starring, but it has not been made.

During the Second World War Schulberg served with the O.S.S. (Office of Strategic Services), working with John Ford's documentary unit, and he was among the first servicemen to help liberate the concentration camps. Gathering photographic evidence of Nazi crimes for the Nuremberg trials, he drove to the Bavarian chalet of the documentary film-maker Leni Riefenstahl to arrest her.

After the war Schulberg wrote extensively about boxing and was chief boxing correspondent of Sports Illustrated, and in 1947 he wrote about the gangsters who controlled the prize fighting racket in The Harder They Fall, which was to become Humphrey Bogart's last film, in 1955. In 1981 he wrote the biography, Loser and Still Champion: Muhammad Ali, and in 2002 he was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame.

After his friendly testimony to the House Un-American Affairs Committee in 1951, Schulberg stated, "What's painful is to have believed in something that sounded so right, and that turned out the way the Soviet Union turned out. I didn't like the way the party was trying to take over the Screenwriters' Guild. And nobody came out and said that Stalin was killing more people than Hitler." Many commentators have identified On the Waterfront as a form of expiation for Schulberg and its director Elia Kazan, but Schulberg denied this.

"It's total, total, nonsense," he said. "In writing On the Waterfront I was interested in social conditions on the waterfront, drawing a truthful story, not in justifying my position. It's a shame that an inaccuracy like that has become a 'fact' when it simply couldn't be more wrong." The film won eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay, though Schulberg felt that the Brando figure should have been killed at the end for testifying against organised crime.

In 1957 Schulberg and Kazan reunited for the acerbic tale of a Glick-like figure who has success on television, A Face in the Crowd, starring Andy Griffith as a war-mongering country singer who almost becomes President. The following year Schulberg wrote and co-produced, with his younger brother Stuart, Nicholas Ray's Wind Across the Everglades, an off-beat drama about conservationism, which was not a success.

After the Watts riots devastated part of Los Angeles in 1965, Schulberg formed the Watts Writers Workshop in order to bring some artistic training to inhabitants of the impoverished area by teaching black youths to write. The project lasted for six years, and spawned workshops in other cities. A supporter of Robert Kennedy's presidential campaign, he was with him at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles at the time of his assassination. "Sirhan shot him then ran right into me ... Edgar Hoover hated him so much that there was no real FBI presence. The mob hated Bobby. The mayor hated Bobby. So he had only amateur bodyguards like the football player, Rosey Grier."

Schulberg's four wives were all actresses – notably his third wife, Geraldine Brooks, whose films included Possessed (1947) and The Reckless Moment (1949). She died in 1977, and Schulberg is survived by his fourth wife. He continued to write into his 90s, working in his waterfront house in Quogue, Long Island, and in 2001 he collaborated with the director Spike Lee on an unrealised project about the world heavyweight champion Joe Louis.

Schulberg's articles, short stories and novels consistently criticised the misuse of power and the fight of ordinary people for justice and fair play. "Writers are really almost the only ones," he said in a New York Times interview videotaped for posthumous showing on its website, "except for very honest politicians, who can make any dent on that system. I tried to do that, and that has affected me my whole life." In 2008, the Screen Writers Guild honoured Schulberg with its lifetime achievement award.

Tom Vallance

Seymour Wilson "Budd" Schulberg, writer: born New York 27 March 1914; married: 1936 Virginia Ray (divorced 1942, one child), 1943 Virginia Anderson (divorced 1964, two children), 1964 Geraldine Brooks (died 1977), 1978 Betsy Ann Langman (two children); died Westhampton, New York 5 August 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments