Bruce Wasserstein: Deal-maker who restored Lazard to Wall Street's top table

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the high-stakes, ego-driven world of mergers and acquisitions on Wall Street, there were players, there were stars – and there was Bruce Wasserstein.

For the last four years of his life, he led the venerable Lazard investment banking group. For more than two decades before that, his career was little short of a one man history of mega-deal making.

In the 1980s and 1990s, he was involved in many of the epic take-over battles that reshaped the culture of American high finance: the controversial manoeuvres that gave DuPont control of Conoco in 1981, Texaco's hostile takeover of Getty Oil, Philip Morris's $13bn purchase of Kraft in 1988, and above all the legendary struggle that year for RJR Nabisco, eventually won by the private equity firm Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts, and chronicled in the best selling book Barbarians at the Gate.

"Bruce was just this rumpled mess," a rival once said, referring to Wasserstein's dishevelled and paunchy appearance, often with shirt-tails flapping loose in defiance of Wall Street's prim outward norms. But no one ever questioned his talents. Wasserstein negotiated deals, his contemporaries said, like a grandmaster playing chess. He was an endlessly resourceful tactician, always bubbling with new ideas – and invariably at least one move ahead of his opponent.

He did not go in for small talk, and could wield a savage wit. His ability to persuade his clients to put up ever larger amounts of money in pursuit of their prey earned Wasserstein the nickname of "Bid 'Em Up Bruce," a label he detested. But, as his long time partner Joseph Perella told the New York Times, "he had a great brain. He was basically smarter than 99 per cent of the people you meet."

That smartness was apparent from an early age. Wasserstein was 19 when he graduated from the University of Michigan, and just 23 when he took dual honours degrees from Harvard's law and business schools, where he spent a summer working for the consumer advocate Ralph Nader as one of the celebrated band of "Nader's Raiders."

But his interest in his future line of business only began in earnest during a year-long fellowship at Cambridge University, researching the history of mergers and take-overs in Britain. And not until he joined forces with Perella in 1976 did Wasserstein start his ascent to the summit of power and influence on Wall Street.

The two met when Perella was a junior executive at First Boston investment bank. Impressed by Wasserstein's sharpness, Perella persuaded his bosses to take him on. Soon the pair were running the mergers department, generating half the firm's profits and turning First Boston into Wall Street's premier deal-maker.

But in 1988 they walked out, after a long feud over strategy with top management, and set up their own boutique investment bank Wasserstein Perella & Co, soon known simply as "Wasserella". There, Wasserstein was hired by KKR as an adviser on the R.J.R. Nabisco deal – not as a result of any great love between them, but because the private equity firm wanted to ensure that Wasserstein couldn't work for its opponents.

Thereafter merger fever on Wall Street abated, and in 1993 Perella left the partnership. Wasserstein re-mained until 2000, when he sold the firm to Dresdner bank for some $1.5bn. In the meantime he had be-come something of a local media baron as well, acquiring New York magazine as well as various legal publications. These latter he sold in 2007 (naturally at a substantial profit that contributed to a personal fortune estimated by Forbes magazine in 2008 at $2.2bn ).

Probably inevitably, this hectic professional career was matched by an equally turbulent private life. Wasserstein was married four times and had seven children, one of them the daughter of his sister, the award-winning playwright Wendy Wasserstein, who died three years ago.

The final chapter of his business career, at Lazard, was in some respects a return to what had gone before. Back in the 1980s Felix Rohatyn – then managing partner of the 161-year-old investment house – had made unsuccessful overtures to Wasserstein, but in 2002 its chairman Michel David-Weill finally got his man, hiring him to run its business operations, and also to resolve factional infighting among its partners.

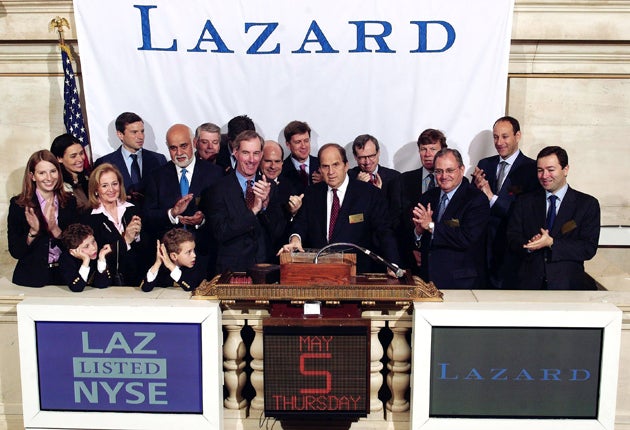

In both goals Wasserstein largely succeeded, restoring Lazard to its place as one of Wall Street's top operators. In the process, however, chairman and chief executive were drawn into a power struggle of their own over the latter's plan to take Lazard public, a step opposed by David-Weill.

In 2005, Wasserstein prevailed, and a $855m share offering turned Lazard into a publicly traded company. The partners cashed in their holdings, buying out David-Weill's stake and effectively forcing him out of the bank with which his family had been linked for generations. "He [Wasserstein] was afraid of sharing power," David-Weill told Vanity Fair afterwards. "He tried his very best – and succeeded – in expelling me."

Bruce Jay Wasserstein, US investment banker: born New York City 25 December 1947; joined First Boston Corp, 1976; founded Wasserstein & Perella Co, 1988; CEO and later chairman, Lazard Ltd, 2002-2009; married four times (seven children); died New York City 14 October 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments